New Moon: Indulging vs. living deliciously

Hello. It's Friday, and having opened up comments to all subscribers, I'm diving right ahead today into the next big thing on my mind. This New Moon post follows conceptually upon the previous one, as I ask myself this question:

If it's possible to still choose and undergo purification without believing in sin, then is it possible to truly indulge in anything without having anything to feel guilt for?

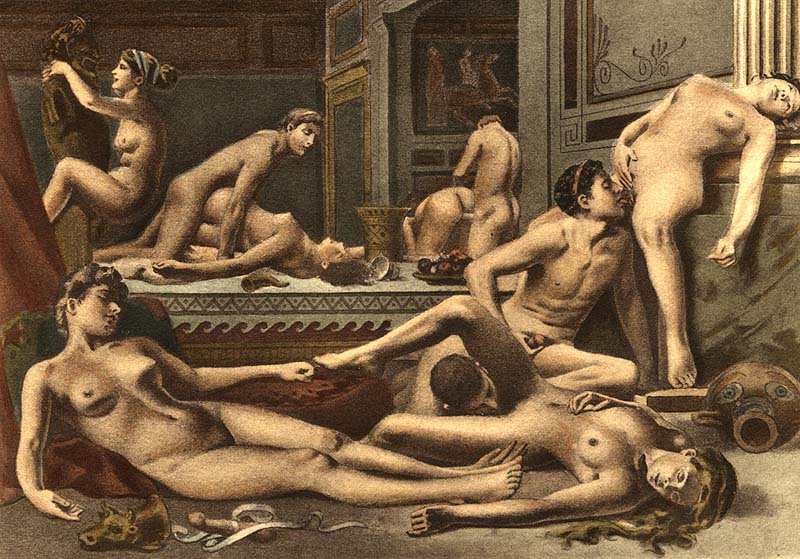

Indulgence is a term that typically assumes there is a temptation, a wickedness, to which someone succumbs, and that this occurs in some sort of hedonistic, carnal, or otherwise sensuous sphere.[1] If I don't believe in sin, if I don't fear hell, then I can indulge myself with anything — whenever I like. But if I choose to always indulge, then the transgressive quality is lost, and it no longer feels like indulgence per se; it feels just like living without self-denial. I can live deliciously as the now-cliché quote bids. So in a sinless cosmology, perhaps indulgence should be redefined.

What can offer the thrill of indulgence if there is nothing forbidden in the first place?

A very brief detour into real ethics

Before I can say anything else about indulgence, sensual transgression, etc., I do feel obligated to draw one very clear line when it comes to consent. Not that I think anyone currently reading this lacks all awareness of what I think about consent — but I want to make one firm assertion due to how I describe my worldview as satanic or Left Hand Path and unfortunately there are other, sometimes prominent organizations or thinkers who use the same language for themselves and who also notably devalue consent or even advocate for sexual violence.[2] A lack of sin or a lack of moralizing attitudes should not be the same thing as lacking an ethical code. I myself tend to leave off the An it harm none modifier, as in my opinion it promotes pathological passivism, but I interpret "Do what thou wilt" shall be the whole of the law[3] to mean the autonomist's creed: everyone, not just you but everyone else, must be able to do what they will. If you interfere with someone else's autonomy, you interfere with their ability to follow that rule, and so in a way you yourself have broken that rule.

So to offer yet another quote, I do not say, "Poor is the man whose pleasures depend on the permission of another."[4] Certain things must absolutely depend on another's permission, namely if those things meaningfully affect the other person's autonomy. My ethics forbid no victimless activities.

In my opinion, this is a more "real" ethics than that of ideological Christianity and its parallels elsewhere. In those systems, genuine respect for others' agency, including one's own, is overlooked in favor of fearful obedience to avoid eternal punishment. Doing something just to avoid punishment is not real ethics; it is survival. Real ethics should mean doing the right thing, whatever that thing is, without there even being any repercussions for doing the wrong thing. But in any case, I just want it understood that what I qualify as the wrong thing is generally something where someone is victimized. That should be forbidden, though what an ideal society's version of forbidding something might look like is a topic for another time. For the rest of this post, please assume that any delicious thrills I'm talking about are thrills experienced equally by all participants.

So now, what of that deliciousness?

Living deliciously in a consumer age

With enough financial and/or social capital, it isn't hard to live with an abundance of things, material or immaterial. In this time of mass production and globalization it's now even easier than before, because there are just so many things to have, because there are just so many things being made and offered. It doesn't matter if those things offer any actual value — whether they "spark joy" as we say now — since with the right marketing or the right cultural entrenchment of certain beliefs, people can be convinced to acquire or experience literally anything at all. And even without quite enough money to spend or favors to call in, many of us can still consume slightly beyond our means through credit programs or through transactionalizing our personal relationships.

Across every political and demographic umbrella, there are people who don't enjoy living this way, but most people in many parts of the world are used to it and do enjoy it at least insofar as it's considered a normal, aspirational thing. Living within the borders of the United States I am especially surrounded by consumerism dressed up in euphemistic, apologetic phrases. Retail therapy. Treat yourself. Self-care.

Self-care.

I hate self-care.

It's not that I don't take care of my physical or mental health within my abilities. Due to my own limitations, which are not unique, I "fail" frequently in certain areas such as eating enough food for every meal of the day, or maximizing highly nutritious food as part of that, or hydrating sufficiently, or redirecting my skin-picking compulsion, or moving around to the degree that I know (not just what standard medical advice would say) would help improve my circulation and alleviate my anxiety... and so on, and so forth, but I do believe in trying, in a very kind and forgiving way, to aim for such things. Similarly, although I can also still "fail" at this, I've internalized many genuinely wise social and psychological practices that can be tritely summed up as "cutting toxic people out of my life," not wasting my time on "distractions from my passions," and giving myself "recharge time" with low-effort activities when the world "gets to be too much."

I do those things, but what I object to is the corporate, mealy-mouthed language surrounding all of it. I object also to the performative qualities that can crop up as people, especially on social media, enter a kind of unspoken contest for who has the best self-care practices to share with everyone else. I object further to how people who are quite capable of fulfilling certain responsibilities can fall back on self-care as a (consciously or unconsciously) manipulative excuse for why they can't fulfill those responsibilities after all. Think of the person you know who's happy to extract your own time and effort to help them, but when you ask them for something that you know they're eminently able to give you, they just can't make time because they really had to enjoy their new bath bomb (and of course post about it online). When this happens in an activist context it can feel especially demeaning. Likewise, almost nothing feels more wretched than when you try to hold someone accountable for a truly unjust thing that they did and their response is to hide behind a shield of self-care: "It's too much for me to engage with your criticism, leave me alone, I have to take care of myself."

But above all else, I object to the fact that while none of the things I described as my own personal "self-care" goals require buying lots of specially branded items or experiences — it all just requires a not-extremely-impoverished situation, not having certain disabilities, and sustaining a modest baseline mental/emotional capacity — in a consumerist society, self-care discussions so quickly siphon off into how you shouldn't just take care of yourself in general, but you should take care of yourself by investing in this one specific product.

Sometimes the products really do offer certain benefits. Sometimes they're scams. Either way, the profit motive behind them requires calculated, insincere marketing. This special reminder app, this special fruit-infuser water bottle, this scented candle, this charcoal sugar turmeric mud mask, this crystal ben-wa ball, this psychic healing ritual, this expensive yoga retreat, this expensive shibari retreat, this camping experience on an organic farm — these things don't care about us, and their creators rarely do either, not in the way where they actually know us and deeply understand us. They simply know the needs that most people have, and they see an opportunity to present something that they have the means to produce as not merely an option to fulfilling that need, but the only option, or at least the unquestionable best. It doesn't matter whether the product will have the perceived effect or not.

Now, given my very interest in indulgence, I'm not an ascetic. Nor am I never going to buy a ridiculously trendy item or enjoy a relaxing vacation partially crafted through someone else's effort for which I reimburse them. If I need to satisfy a necessity and I do actually have some choice about how I acquire it, then if I see (rightly or wrongly) some likelihood that this one product is going to serve my goal, and maybe better than some alternatives, then I may buy it whether it's dressed up in a lot of hype or not; ethically speaking I'm always more concerned about the creator's/manufacturer's labor practices and environmental practices, assuming I have the opportunity to discriminate there as well. And similarly I will gladly consider investing in the occasional luxury because a) I am not immune to commercial propaganda, b) I can create my own fun but some kinds of fun are created better by other people who aren't me, and c) there are some things worth enjoying just because they exist.

I'm going to come back to that very last point in the next section. In the meantime, though, I want to juxtapose what I've described in the above paragraph against the full-blown, quasi-religious culture of consumerism — which affects me but from which I try to separate myself as much as I can. In such a culture I have lost track of the amount of merchandise geared toward witches like myself under the auspices of what I've described before as the New Witchery. So much of it comes directly attached to or branded with The Witch's question: "Wouldst thou like to live deliciously?"

In that story, Black Phillip, or the Devil, asks this of the heroine Thomasin. Before this, he also asks whether she would like the taste of butter, or a pretty dress. But this is in a pre-industrial, pre-consumerist time; he isn't asking Thomasin whether she wants mass-produced butter or special high-end artisanal butter from grass-fed cows. Of course in this setting it would come from grass-fed animals, but more importantly, Thomasin's family has been poor and practically starving for a while; although butter in that time was not a luxury per se and would have been commonly eaten by many English people, if you couldn't afford even one dairy cow and were out of contact with the rest of your community, then you would just not have butter. I suppose one could pedantically argue that the family might have made butter from their goats' milk, but if nothing else at the end of the movie there's the small problem that all the milk-producing goats are now dead. Thomasin is not going to have butter or a nice new dress any time soon. In all likelihood she's going to starve to death alone or, if she returns to the rest of her Puritan brethren, she might face persecution there. Butter and a new dress are suggested to her as indulgent temptations, as treats, but not in the context or language of "self-care." Black Phillip suggests a reality in which Thomasin has ascended so far beyond fulfilling her basic needs that she is allowed to have desires.

Black Phillip doesn't remotely pretend that Thomasin requires these things to survive. By contrast, consumerism is far less honest about this type of thing. An enormous number of specially packaged items and experiences thrown in our faces are not unique and exclusive answers to things that we need, nor do they absolutely address things we need at all. They are invented desires that get justified with pretensions of necessity. It's bad faith arguments all the way down. This is your emotional support espresso machine.

A consumerist lifestyle is not living deliciously at all. How fitting, of course, that the United States is both the consumerist heartland and a colonial project first begun by Puritans, those masters of self-denial. To maximize capitalist profits, it's not enough to actually sell everyone what they need, so completely useless garbage must be relentlessly generated and sold as well; but it would be shameful to acknowledge that the garbage is garbage, and that people have been taught to want garbage, so just frame it as a need. Sometimes these framings are as flimsy as paper but people buy in anyway. How many times have we heard people talk about how they "need" to catch up on binge-watching a particular show on a streaming service? If there's any need there at all, surely it's just to combat the social pressure of being "out of the loop."

I think the best way out of that game is to stop playing it. To learn and practice honesty about needs vs. desires.

"I don't need anything. I want."

On one pay-locked post in February I spent some time grazing the very surface of my love for one thing I do relentlessly binge-rewatch every year: Twin Peaks. I'm not going to go into it very much here, but there's a phrase uttered by one character in the relatively recent third season (Twin Peaks: The Return), which is: "I don't need anything. I want."

This character, whose identity I won't reveal right here, is definitely positioned as evil, and the way they utter those words is emphatically ominous. Menacing, perhaps. Every time I rewatch that moment, I take away the sense that this character demonstrates how frightening and intimidating it is when somebody has no needs whatsoever. Without needs, they cannot be manipulated by other people. To be without need is an unfathomable power. Combine this with the fact that they still want things, and you have an unbridled devouring force — and it will eat you for pleasure, not because it's hungry.

How would it feel to hold that power oneself? To transcend needing, and become pure wanting. I'm referencing far too many quotes at this point, but of course with great power comes great responsibility — what makes the only-wanting character in Twin Peaks evil is not merely that they want things, but that they only want things for themselves, and they will stop at absolutely nothing to achieve those things. In other words, they have no qualms about creating victims. There's even a supernatural force inhabiting them that thrives outright on others' suffering. Here, no responsibility is taken for all that power. But I want to suppose that we could live under more benign, autonomy-respecting circumstances of not needing, only wanting.

To me, this would require a world where we aren't competing over resources to fulfill our needs in the first place. It's not a capitalist world; that much is certain. In this other, better world we would always begin with certain needs, and not everyone's needs would be identical either, but those needs could be met with such little effort that pragmatically speaking they don't exist — not as a thing to constantly work toward achieving. Then what we would be left with is just the things we idly, spontaneously want. Things we can survive not having, but delight absolutely in receiving. And we could honestly acknowledge our wanting, our desiring, because there wouldn't be this current sense of audacity for having that kind of agency, or for craving "frivolous" things while other people have nothing.

The only real limit in such a setting would be that no matter how abundant a planet we have in principle, it is possible to exceed those resources even without 1% of the population hoarding most of them. So the world I'm describing is not actually one of constant excess. That's not sustainable. Sustainability does require a sense of moderation.

I know this might sound awfully close to arguing that even without sin, even without shame, we should never really aim to just want things, because as wanting exceeds the realm of our needs, we thus run the risk of exhausting our surplus resources; so let me try to reiterate and emphasize a couple of ideas.

- A state of optimal want is, again, surviving not having things while delighting absolutely in receiving things. We're used to constantly harboring needs, because that's about survival. A want, a desire, is something that should operate purely upon whim. We can ultimately control our whims. Thus I believe that a society where people only want, without really needing, would not have everyone wanting a maximum amount of everything all the time. We would be able to delight in simple, ephemeral pleasures, not just in constant, spectacular ones. If we lost that kind of control, we wouldn't be talking about wanting things anymore, we would be talking about addiction. And addiction appears most easily when there are unmet needs.

- If this were a truly conscentious, equitable society, people would have common sense around "dangerous" wants. If everyone were invested in everyone meeting their own needs, then people would be operating from the principle that wanting certain things is not worthwhile, because to fulfill those desires would necessitate upsetting resource distribution, thus creating scarcity and potential risks to the fulfillment of your own needs long-term, never mind other people's needs.

Anyone is free to question whether such a world is pragmatically possible, or whether we will achieve it as soon as we ought to for our own (and many other species') survival. I'm agnostic on both fronts. But aspirationally speaking, this is my vision of a satanic ethics for abundance, a satanic ethics for desire, that does not fall back on ideological Christianity's morals wherein the very act of wanting anything is sinful, wherein we must be grateful for whatever we are given because we deserve nothing whatsoever, and wherein we must not question why we didn't get more.

Perhaps we can't have everything we ever want. But at least if we had everything we needed, we could want things — and have the things we want — much more often. To close this section with a Twin Peaks reference from the much earlier, original series, we could more realistically adopt the practice of each day, once a day, "give yourself a present," without any justification. Not as a marketing slogan, not as a means of soothing your troubles. Self-care doesn't even enter the mix. This is the real living deliciously.

Ecstatic, extraordinary experience

The delicious living described above is an ideal, a theory, a dream. Turning back to consensus reality, I know that most people are not living like that, not even exceptionally wealthy people since their gains are so near-universally unethical after a certain point. In the world around me, in the world I still continue to occupy, I would like to live deliciously, but I have too many needs that will not be met unless I work — typically wasting precious grains of my life's hourglass.

It's here that I finally think I see a satanic framing of indulgence fitting in. As long as I live under these circumstances, as long as I'm dragged along in the current death-march, I need to seize what moments I can to remind myself that I can also want in addition to needing. To remind myself of my own agency and personhood. Indulgence should be something revolutionary, riotous, rebellious. It shouldn't be about "succumbing" and "doing things you normally shouldn't," but rather in showing ourselves the thrill of raw existence.

Indulge, to remember what to fight for. Indulge, to remember what we're capable of.

In this mindset, the language of consumerist self-care doesn't particularly enter my head. If I might have to buy something particular in order to indulge the way that I have in mind, so be it, but this should be a truly self-directed process, not something being offered algorithmically up to me. If I need to stop what I'm doing and perform an activity to take care of myself, then I'll take care of myself, but that's basic wisdom, not indulgence at all.

Some of the activities I could choose for indulgence might be the same that I could choose for self-care, but the underlying motive differs. Suppose that I choose to eat some ice cream. If I do it for self-care I'm essentially thinking, "I feel horrible, and lacking an ability to immediately solve the reason why I feel horrible, having some comfort food would at least bolster my spirits temporarily." Maybe if I'm resorting to eating ice cream for psychological self-care a great deal, that's going to make me feel horrible physically after a while, but supposing it's not my only strategy, I see nothing wrong with it. But it's not really indulgence the way that I'm thinking of indulgence now. If I truly indulge myself with ice cream, my thinking is more like, "I feel lovely, and you know what would make me feel even more lovely? Getting some ice cream."

The ice cream example works potently for me because it also feels like the difference is illustrated by how I feel about the ice cream I keep in the freezer vs. the ice cream I go out to eat from an ice cream stand. But actually, until I wrote all of this out, I think I myself had conflated the two situations for a while. Consumerist self-care logic at work in my own mind.

For a less all-ages kind of example, I now consider kink. I've already framed many kink activities as archetypally ecstatic. And now I think they are, or should be, archetypally indulgent — as should any ecstatic activity. Because these are things to do without any specific external aim; they are to be done for their own sake. I agree with the notion that kink can serve a kind of therapeutic, self-care-aligned function without being unhealthy, but I think it will always become unhealthy if it's not also coupled with literal therapy or some non-erotic equivalent, at least assuming someone needs help with whatever they're using kink to address. This doesn't mean kink shouldn't be an important pillar of adult lives; it should, but ideally in our current, unjust world it can be a dominant (no pun intended) axis of indulgence as revolt.

I don't have a tremendously grand conclusion from this particular place, but thinking of revolution does happen to shift things in an appropriate direction for next week. And I am satisfied for now with where to leave the question of indulgence in contrast with last month's question of purification. On the sinless Left Hand Path, both purification and indulgence remain and serve valuable roles, but here they are matters for our current, mortal lives, not for paving the roads to heaven or hell.

[1] In the history of the Catholic Church, "indulgences" were not understood in this way — they were literal permits you could buy or otherwise earn from the Church in order to "waive" sins of many kinds. This was one of the Church practices that early Protestants (especially Martin Luther) objected to, and although I don't think indulgences have ever quite been abolished, they're enormously out of favor. Regardless, I don't think most people today in anglophone, Christianized cultures understand indulgence as a transactional remission of sin; it's just associated broadly with illicit hedonism, although the "all right, just this once" attitude persists.

[2] As readers who already read this post may be aware, I'm referring not exclusively but significantly to the Church of Satan (or any other flavors of LaVeyan Satanism) in the former case and the Order of Nine Angles in the latter case. On paper, the LaVeyan stance on sexual assault is summed up in the Fifth Satanic Rule of the Earth, "Do not make sexual advances unless you are given the mating signal," but in practice, LaVeyan Satanism's overall politics are reactionary or crypto-reactionary enough that the Church of Satan's patriarchal, consent-dubious reputation among other satanists should be unsurprising. At the furthest extreme, meanwhile, the Order of Nine Angles is a theistic satanic organization (in its own words, anyway) known for things that I'm not going to share in unhidden detail here, I will just link the Wikipedia rundown. Read at your own risk.

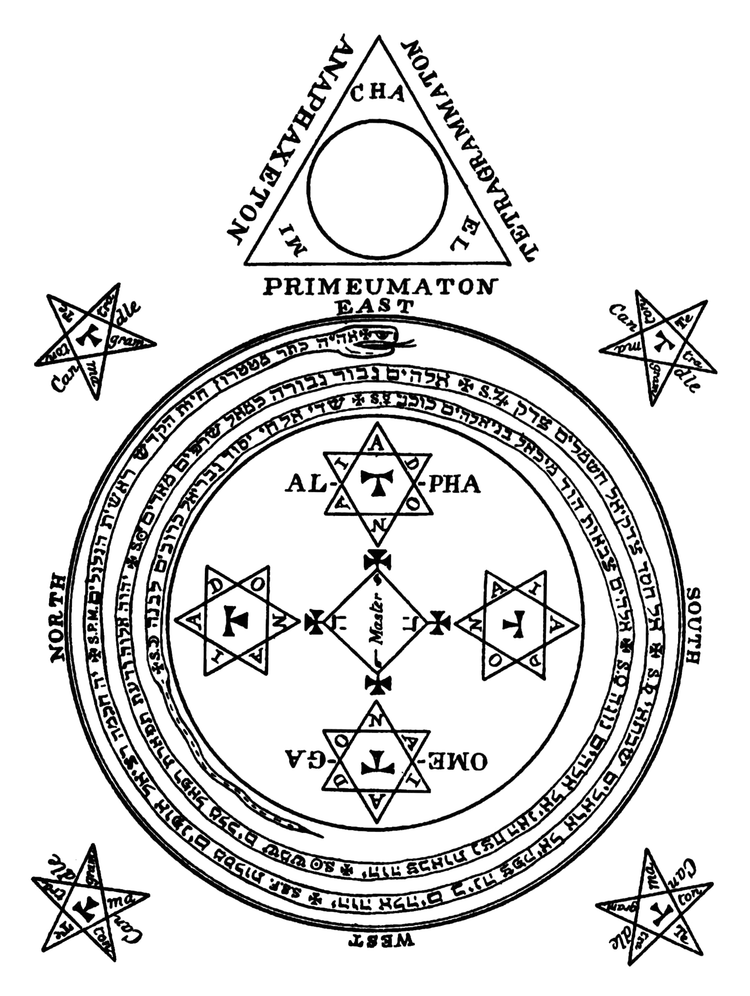

[3] I know this is not a satanic rule so much as a Thelemic one codified explicitly by Aleister Crowley, but modern satanism of course owes an enormous conceptual debt to Thelema, adopting many aspects wholesale, and Crowley remains an inspiration to many satanists even though he was an abjectly horrible, abusive person. My rites adopt the rule Do what thou wilt because of the interpretation that I impose upon those words, not because I'm an uncritical Crowley fan. I have never read his work and I only ever consider it for research purposes. See footnote [2]'s linked newsletter post for more on that too.

[4] By the way, it's easy to imagine the Marquis de Sade saying this, given his own... situation, but I'm pretty certain that's a common misattribution. It's really just Madonna, isn't it?

Thank you for reading. Last night I did an online presentation for a (my?) local leather club about ritual D/s, and since this newsletter got linked at the very end, I'm not sure if any new, curious eyes have wound up here, but if so, greetings. Also, I'm looking ahead immensely to one, arguably two weeks of posts relevant to the imminent holiday of Calan Mai, or so I call it in my practice. (You may more likely know it as Beltane, Walpurgisnacht, or May Day.) The second such post will be locked to paid subscribers only, but both are going to be an utter explosion of ideas, feelings, and moods.

Member discussion