New Moon: Purification without sin

Content warning: this post probably won't be heavy reading for most people at all, but some parts may feel hard for people with disordered eating or who struggle with body dysmorphia. I know because if I were the one reading this piece, my own such challenges would raise their head, even if not violently.

Good morning. It's Friday, the tail end of a week that's been difficult for me. The reasons might bear getting into for some other posts, but probably those more of a Last Quarter flavor. The New Moon has now passed and I'm making an effort to put my thoughts more in that space.

It helps that to some extent it suddenly feels like spring — and not in an unnatural, wrongly-timed way. I don't know what my favorite season is anymore, but I know that for my mental well-being, spring is the best. It combines my ideal temperature range with increasing light levels (rather than decreasing), while falling shy of anxiety-exploding heat waves and severe sunburn risk.[1] Likewise, spring here usually avoids storms, and in my current lifestyle it involves less hard work than winter or summer. The two big sacrifices I have to make are physical: my migraines peak this season, and over the past several years I've become a spring allergy sufferer. But sometimes I accept that trade gladly, and I think spring feels precious to me insofar as true spring meteorological and ecological conditions in my region lasted only about 6-8 weeks in my childhood; now it lasts probably about 4-6.

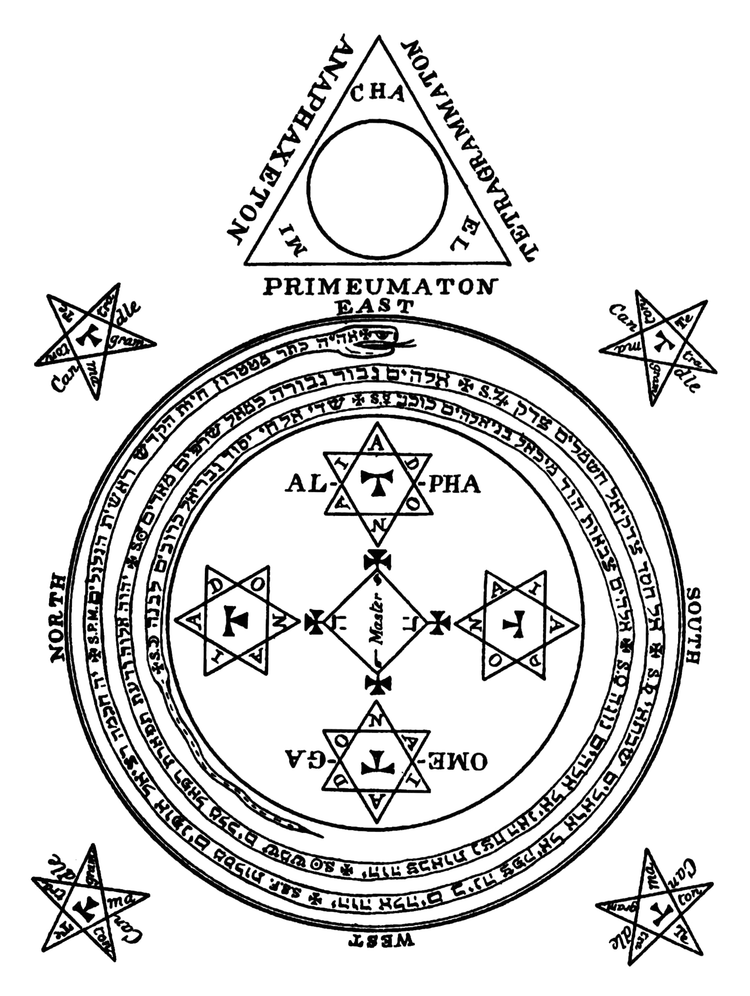

Because I tend to feel good in spring, it's an ideal time to get big shit done and move my body around a lot. As mentioned last week, I don't think about Ostara (the spring equinox) in terms of "new beginnings," but I do increasingly think of it as a time to cleanse, purge, release all the built up indulgence of winter turmoil, and experience an austere simplicity before summer's abundance, or summer's onslaught depending on the forecast. In light of this purgative ethos, I lit a stick of incense on Monday to experiment with the notion of "purifying" smoke.

Now, this experiment was not completed because I hadn't lit incense in untold years, and it turned out that at least one member of my household, possibly including myself, is too sensitive to it. It might have been the specific resin choice — frankincense — so later I'll have to try a different one and see if that matters. If incense doesn't work out, maybe I have to finally become a scented candle person. I just really want some way to feel like I'm purifying my house this time of year. But what does purity really mean?

For Christians, this time of year is Lent, a matter of intentional deprivation especially where diet is concerned; and there's a kind of sense to this beyond scripture insofar as now is the very leanest time in agrarian lifestyles. Meanwhile in Judaism it's nearing Pesach, when existing dietary restrictions tighten further mostly in symbolic remembrance; but symbolic or not, this mirrors the opposite time of year for purgative fasting on Yom Kippur. Many other religions have ritual fasts or other forms of close discipline at some point in the year, whether fixed or rotating; and in any such case, there's often a sense of joining monks or other ultra-dedicated worshipers in their ascetic practice. Of going without the worldly, and thus being pure.

As someone on the Left Hand Path, as the devotee of no god but an anti-authoritarian god, I can flinch at certain ways of talking about purity. But I think there are some other ways to understand purity that do fit into a satanic framework and for that matter into animist/pagan traditions that similarly position themselves with sinless cosmologies in contrast to Christianity[2]. And as I transcribe my thoughts about these matters, this post is ultimately going to turn toward the topic of ordeal, and of why I view ordeal as valuably purgative.

What is owed to the community & what is owed to the self

I do not believe in sin, in ritual uncleanliness, in negative karma.

Now, that's not to say I don't believe in ethics. I think all cultures have good reason to develop formalized debt relationships and honor systems wherein people owe each other gifts for gifts and recompense for transgressions; but when it comes to discretely quantifying an amount of uncleanness that someone has accrued, or the amount of money that must be paid or work that must be performed in order to no longer be unclean, this is where folly sets in. Not because two people alone can never agree a fair exchange with one another (they can), but because it's not possible to legalistically determine a one-size-fits-all spiritual repayment plan that's truly fair to everyone. The paradox is, of course, that in order for people to live together in a community, there must be some baseline rules of interaction and connection, otherwise people have no reason to trust each other; yet to create any rules is to restrict some degree of autonomy for individuals as well as autonomy for people to work certain things out among themselves instead of needing to appeal to an authority.

It's difficult to find the right balance. It becomes even more difficult when the debts that people owe each other are meant to extend into some afterlife, or when the fact that one person has broken even a small piece of the social code manages to be treated identically to one person making a far larger mistake. In situations like those, what somebody owes can rapidly become less important than the fact that they owe anything.

But if that's a risk when we're talking about groups of individuals, at least it's hypothetically worthwhile to figure out universal-ish laws about good behavior for those groups. By contrast, there is really no benefit to extending universal laws about good behavior to behavior that only affects you — to defining "victimless crimes." If there is no victim, I see no crime. Socially or institutionally policing people about what they choose to do with their own bodies, for example, is a morally bankrupt position to me.

Obviously I hold this criticism for Christianity and other historically or situationally repressive mass religions, because of that very repressiveness. But are they the only offenders? Not at all. In pop witchery and in wellness fads, so many people and companies want you to be free of "toxins," whether these are framed as physical or supernatural; and more often than not they'd just love to sell you something to solve the issue. These people and ad campaigns rub me the wrong way most of the time. Either the thing I'm supposed to cleanse from myself is something I don't want to get rid of at all, or it's so amorphous that clearly the point is to feel pure more than to be purified of any one thing. Why do these people say I'm supposed to purify a magical space before practicing something there? Wouldn't it be just as effective to advocate for doing whatever feels necessary to enter a magical headspace, without the language of cleanliness? When I told my owner that I wanted to burn incense for Ostara, I felt obliged to mention "purifying smoke" in a sardonic tone with air quotes, because although I agree that smoke bears purgative connotations — smoke sends life running and thus implies sterile or at least virgin premises, while the right scent for smoke is also ironically soothing — I find talking about smoke as a purifier to be painfully cliché in pagan and occult circles.

All too often, I believe that in many if not most languages and cultures we fall prey to a tendency to externalize things about ourselves that we want to be rid of. To take comfort in imagery of invaders, diseases, abstractly malevolent bigotry, and material evil, even though sometimes those very real things[3] aren't the actual problem. Each of us certainly does face a great deal of systemic and otherwise interpersonal factors in why we ever feel like our lives are terrible, but that doesn't mean that none of us are responsible for anything we do or experience. We should act accountable for the things that are within our ability to control. And in turn, we should show enough love for ourselves that we don't feel the need to pathologize aspects of our bodies, emotions, or spaces that are uncomfortable to us but — to use a much abused phrase — valid.

For instance, I have a troubled relationship with how my body looks; much as a lot of its appearance comes down to genetics and the constraints of a low income, I know that objectively speaking I eat more sugar than I "should," to the point of showing signs of a mild psychological dependency on sugar, and that I don't exercise as much as I legitimately "could"; but also, I do myself no favors by thinking of my habits as wicked, possessing forces like Gluttony or Sloth. No matter what I choose to try eating (or not eating), no matter how often I work out, I'm never going to improve my relationship with my body by centering that improvement process around shame. That's the most counterproductive strategy I can possibly think of. I stopped owning a scale years ago, I don't count calories, and over the past few years I've felt myself getting closer and closer to actually loving my body exactly the way it is. There's part of me that still can't help thinking of highly processed, sugar-loaded, hydrogenated, microplastics-polluted foods as functionally indistinguishable from mild poison — but the dose makes the poison, and it's not possible to eat a diet that's not unhealthy for you in some way. I feel myself very close to uncoupling my relationship to sugar from my relationship to my appearance, and though I've been going to a gym semi-consistently for six months, I have exactly zero goals there besides:

- "Move around a lot for an hour, twice a week," because not-moving exacerbates my anxiety

- "Maybe eventually be able to comfortably run five miles," although I would also accept something lower-impact like "be able to bike ten miles" or even just "be able to survive using an elliptical," and all of these possibilities are not about achieving some medical standard of cardiovascular/pulmonary health but rather about some very basic things that I can't do at the moment but sound cool to try

- "Maybe eventually be able to deadlift 200-300 lbs.," because again, that sounds cool, especially because I stand 4'10" but (if I do say so myself) I have a stocky, very-broad-shouldered build that I would love to prank people who think someone my height (or gender) can't lift fuckall

None of the above involves purity. Using the language of purity would ironically ruin what I'm trying to do. I have merely devised private standards that I'd like to hold myself to, in order to accomplish something that matters to me.

The tricky truth, though, is that if I'm the only person managing these standards, I'm responsible for deciding when I've let myself down, and what to do about it.

Psychic bondage

I'm going to move away from talking about diet or exercise for the rest of this post, because although my personal choices about those things have been a big part of my life lately, I'm still painfully conscious of how "look at this diet/exercise thing I'm doing for myself, and at what I do to keep my private diet/exercise promises" can come across in our extremely fitness-obsessed, comparison-driven society. I don't want anything I could say about my "self-discipline" in that one respect to sound like passive-aggressive advice to other people.

Honestly, whatever I offered about my fitness self-discipline would sound fairly ridiculous, too, because at the end of the day, in this one area I am still not that "disciplined" and I feel rather close to stripping myself of all pretension at becoming such.

I hold myself to much, much higher, perfectionistic standards in other, non-physical areas. And when I feel like I'm not behaving according to these standards, it's a sense of psychic bondage: I understand what things I would like to do and what kind of person I'd like to be, but even after adjusting for external interference, something in me is tied to doing things I see as wrong or as misaligned with my self-concept. I so often want to be more patient than I am, as well as more flexible, less pessimistic, more emotionally regulated, less catastrophizing, more experimental — and yes, I know that lots of other people want to be these things, and may also fall short of their desires, but I will assure even readers who know me well that deep down, in my most hidden and vulnerable places, which are where my behavior comes from in times (or contexts) of greatest stress, I can be markedly impatient, inflexible, despairing, and boring.

The causes are still not necessarily things that can or should be assigned moral weight; they can include trauma or prejudice or other thought patterns induced through accumulated life experience, and they can also include probably-congenital traits like my autism or my anxiety (whether as an extension of my autism and as a separately considered phenomenon), as well as repeat miscalculations and unexamined habits. But even if I know I shouldn't judge myself too harshly for these flaws, I do still see them as flaws. I feel like I owe it to myself to learn different behaviors even when my moments of failure affect nobody but me — and even though I have an established reputation with many people as a diplomatic, innovative, forward-thinking person. What those people see is not the person I see.

And likewise, though none of my mistakes leave me dirty, they leave me feeling burdened and restricted. In that sense I do seek to purge myself, only it's not about removing filth in order to be clean, nor even about removing toxins in order to be healthy. When I want to purge myself in order to act the way I've decided I should, it's about removing (unwanted) ropes, clasps, locks. I may allow myself to use purity and purification as metaphors of convenience, but what I'm really talking about is freedom and liberation, or more wordily, alignment of my self-image with my behavior and a process to achieve that alignment.

In the context of trying to be "clean" — a basically punitive act toward my imperfect but worthwhile self — the worst thing I could possibly do to myself would be to undertake ordeal work. Maybe some people feel differently, especially people who are self-described emotional masochists[4], but I should be re-training my perfectionism, not encouraging it. However, in the context of purity-as-release, this is where I ultimately see ordeal providing transcendental opportunities.

Ordeal loosening the knots

As I've written before, I've never quite experienced something that I would qualify as a full-blown, true ordeal ritual. In turn, it's also been a little while at this point since I experienced any activity, say in kink, that had ordeal-like characteristics. But when I at least think about what ordeal-like experiences I've had before, what ordeals I've heard about others having, what "theories of ordeal" have been written by Thista Minai, and what going through therapy is like, I've surmised the following positive effects that an ordeal must have when performed in the right way for the right reasons:

1. Catharsis of trauma

I could use the word catharsis in all the later numbers here, but I want to use it with trauma especially because I think that too often in discussion of trauma — especially online — there arises a temptation among some of my fellow survivors to frame trauma as a now-permanent state of being. A permanent influence on our behavior. A permanent "damaged" quality of our personalities. In this framework there's no real reason to avoid re-perpetuating trauma on other people, because there's no acceptance of the possibility that we can act in manners informed by things that are not just our trauma.

Speaking for myself, I find such a mindset runs counter to my hope to actually heal trauma and to avoid ever weaponizing it against other people. But I do see some kernel of truth underneath the potentially explosive consequences: there is no turning back the pages on what's happened to me. Unless I actually could wipe my memory of all traumatic events — and I wouldn't choose to do this, since I've learned some positive lessons from a few of them — there's no way for me to behave that isn't at least slightly influenced by what trauma has taught me. And much as it can hurt to consider, I must continually accept the likelihood that however much healing I manage to accomplish, I will never heal completely; expecting myself to attain a magical state of Permanent Okay is so unrealistic that I would likely make my healing process unnecessarily difficult.

This is the setting in which I think catharsis of trauma is important to pursue, and in which I see ordeal playing a meaningful role. The film The Babadook deserves its hype for how it portrays the "solution" to someone's grief from a traumatic incident: that you never let yourself be consumed, but that you also don't try to ignore it. In the right pockets of time, it's helpful for me to go down to the dark cellar of my heart and pour out my fear, my fury, my helplessness, and in that long terrible moment say to myself no, I do not need to feel all right. And then, critically, to retrain just enough control over myself to go back up from that cellar and put what's down there out of my mind. I would love to one day create or help with intentional rituals for letting myself and others just feel fucking terrible for a little while, without wallowing in it forever.

2. Forcing bias confrontation

I'm not a cognitive behavioral therapist, but as a lot of my therapy right now incorporates CBT I've become more familiar with what it involves than I used to be. I understand why some people might not like it (or DBT) but at the end of the day I see a lot of merit in treating repeat behavioral mistakes like our brains are having thoughts and intentions that keep to certain weathered "grooves" on a course, and so to act differently — to be the people we'd like to be — one fair approach is to work on pushing our brains out of one groove and establishing a better groove for it instead.

This especially applies to when I hold a particular bias about something. I don't really mean bias in a political way — I just mean a preconceived idea of any sort. Any ingrained expectation. Sometimes I've developed biases based on very good evidence for why I should believe such-and-such thing is going to occur, so-and-so person is going to respond to me in some way, etc.; but just as often, especially in situations that I'm more instinctively nervous about, my biases are just there as a coping mechanism. And it doesn't matter whether trauma has anything to do with it. Not all things that we fear are caused by trauma. Not all biases we hold are related to trauma. Sometimes we are just used to interpreting the world a certain way because the model we create seems helpful at the time, even if we're wrong.

With that in mind, I think that although nonconsensually torturing someone to force them to accept a "new reality" is morally indefensible, consensually opting for an ordeal ritual sounds very appealing to me as a means for getting myself to get over myself and a lot of the bullshit I throw in my own way. It could involve roleplaying situations that scare me, with an outcome that's either within my control or not as bad as what I'm afraid of. It could involve facing literal phobias; kink-wise incorporating spiders on my body would an absolute turn-off and hard limit, but I could still imagine taking part in an ordeal designed to expose me to spiders in ways that would trip my fear meter only far enough to realize that not all spiders are dangerous or actually that frightening. I could also see value in ordeals where I ritually dramatized the resolution of a long-running cognitive dissonance, in order to fully confirm the way I think I ought to be handling something in the future. And so on.

3. Resetting burnout (especially autistic/neurodivergent/disabled burnout)

Staying alive is by definition an energy drain, and so is staying alive at a level of functionality that's personally fulfilling to each of us, although that precise level varies from individual to individual. I know that for some people, myself included, it's especially hard to achieve "optimum personal functionality" — a grotesquely clinical-sounding term, I apologize — when we are also having to play a separate meta-game of doing everything we need to in ways that our peers, families, and general society will most naturally accommodate. Masking harmless but non-neurotypical traits is very hard. It's also hard to do anything at all in life where most people expect you to have certain body parts or cognitive faculties and you actually don't have those things so you're having to creatively invent workarounds that not everyone is prepared to accept. And the longer someone, including myself, goes like this without a break — the more burnt out they eventually become, sometimes to the point of even having reduced functionality from their original baseline.

When I've gone through ordeal-like experiences, namely very intense kink scenes, I mostly don't experience "drop" like some people describe, at least not if I have proper aftercare. Instead I tend to go through the next several days feeling remarkably resilient and unstoppable. The intensity of what I've just endured has reminded me I can endure many other things. Kink should never substitute for therapy — I do both for a reason — but the longer I go without some heavy s/m during stressful, burnout-inducing times, the more I find myself craving the kind of factory reset that I get from screaming through an impact scene.

4. Releasing anxiety itself

In some ways this is all covered by the above points, but as someone who has anxiety I want to emphasize the very important challenge that I face with this condition: I would probably have anxiety even if I had never experienced trauma, even if I had no unhelpful psychological biases, even if I weren't autistic. Or, even if my anxiety were wholly derived from these other parts of myself, there are ways in which my anxiety manifests that are really only worth treating as anxiety. That is: as completely unnecessary tension. Hyperactive amygdala going haywire.

I'm on the second of two therapists who have each touted the mental health benefits of bilateral stimulation: that is, receiving a session of (rhythmic? regulated?) sensory input on both sides of the body. This may take the form of physical contact, whether gentle or firm, pleasant or unpleasant, whatever feels right; it could also be sounds in either ear or someone's eyes tracking from left to right and right to left. From a scientific angle, I believe it still isn't well-understood why activities like these seem to have some kind of effect on improving self-reported mental health — only that an effect exists, and that it may not be placebo[5]. But from the angle of my subjective experience, there's no question that bilateral stimulation helps me, and it seems to help in the way of "disrupting" my baseline state of being. So far it's helped with active trauma recovery in a therapy context, as if the metaphorical jolt it provides gets my brain out of deep grooves created by those past experiences; in therapy my stimulation type is eye movement, but after doing ordeal-like kink (or even just intense sex) where there's definitely bilateral tactile stimulation, I feel generally less anxious even without having targeted a particular brain-groove.

Becoming like the Fool

As I've referred to ordeal throughout this post, I've often found myself picturing it as a matter of inundation, biased by my own preferences and sensibilities. But I could very much understand ordeal by deprivation, whether through limiting one's senses, through going somewhere all alone, through starvation or thirst, or through removing some other kind of routine experience. I'm sure this — as much as any belief in earthly things being "impure" — is why the earliest Christian monks were hermits, why monastic traditions across the globe incorporate some ascetic component, and why so many religious and ritual systems practice routine fasting (in springtime or not). Of course, whether choosing inundation or deprivation for one's ordeal type, there is still a risk of developing an addiction to the thrill, or to the austerity, even if you aren't using the language of purity.

But I think at this point I've laid out why in the best of circumstances, embarked upon with full risk-awareness and consent, a symbolic purge now and then holds a great deal of promise. Purgative ordeal remains within my prospective toolkit for future rites. Not to avoid pollution or corruption, but to become un-jaded, to recover a sense of adventure, to set out into the world feeling unencumbered and uninhibited.

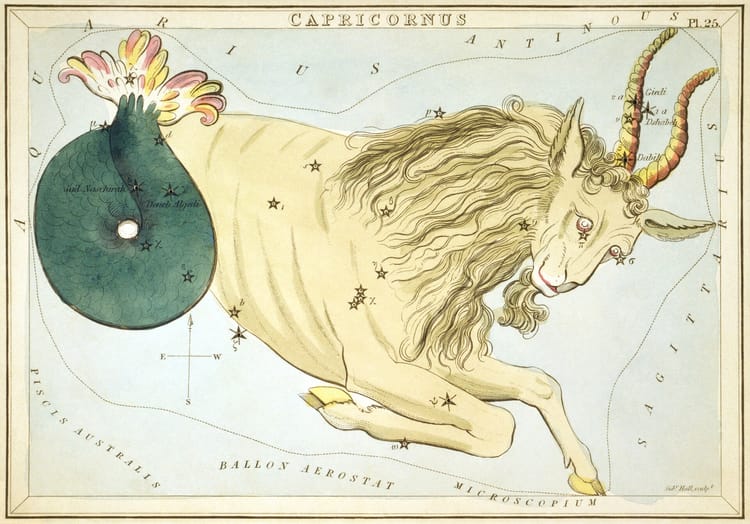

When I welcome the new season at Ostara, the tarot card that I place on my altar space is the Fool. I'm going to leave you, and myself, with that image as we move through the rest of purging season. And hopefully the next time that I write about ordeal work, I'll have come a little closer to new experiences that can inform my thoughts even better than the armchair work I've done so far.

[1] I'm in the category of skin pigmentation (or lack thereof) where on a summer day between 10 AM and 4 PM I basically have to avoid direct sunlight unless I can put up with wearing high-SPF sunscreen. From May through September I tend to use a UV-blocking umbrella, and I try to take care of outdoor work early in the morning or close to dusk. I raise none of this in a particularly "woe is me" way but will note that because high wet bulb temperatures can exacerbate this problem even further and I've also developed heat exhaustion several times in my life, I do treat global heating as a matter of my personal safety, not just of existential/spiritual dread.

[2] Or, for that matter, in contrast to other regionally hegemonic religions — as although Christianity has arguably had the widest and most recently palpable colonizing influence, it's not the sole culprit for the disruption of indigenous animist practices or the suppression of rival (spi)ritual movements.

[3] Well, the concrete reality of evil is fascinatingly debatable, but I'm not going to get into it here.

[4] I am a physical masochist only. Emotional masochism is one of my limits aside from what I can inflict on myself with depressing music, movies, and books. Somehow I might be capable of emotional sadism in exactly the right context (consensually kinky, that is) — but that's again not very relevant here.

[5] I think placebo is extremely powerful in its own right, so here's yet another thing to file under things I should write about later.

Thank you all very much for giving this newsletter yet another read. This time I do feel obliged to ask once again for people to convert their subscriptions to paid ones if possible, because it's been a few weeks since I last mentioned that and publishing this is still costing me money every month. I have absolutely no lofty ideas of being able to make a living off of writing here (would that it were so simple) and not even any intentions of being able to pay off some long-running debts, but if I could at least break even with this project it would still mean very much to me and help ensure that I can keep justifying all of this. Nevertheless, the next couple posts will still be free to read; check your inbox over these coming Fridays for spring gardening thoughts and the very "witch blog" topic of... moon magic.

Member discussion