Spring Equinox + Last Quarter: Regrowth from decay

Hello. It's Friday, and despite the upcoming holiday on the Wheel of the Year, I have something truly short written here. This is partly because it's a holiday that I'm still figuring out my relationship with after many years; but mostly my deepest thoughts this week happen to be rather self-contained. I'm getting closer and closer to regularly writing meditations that are not by necessity overwrought essays. My foundations are already in place. Some posts will remain longer than others, but for today there's just a morsel.

The middle of all things

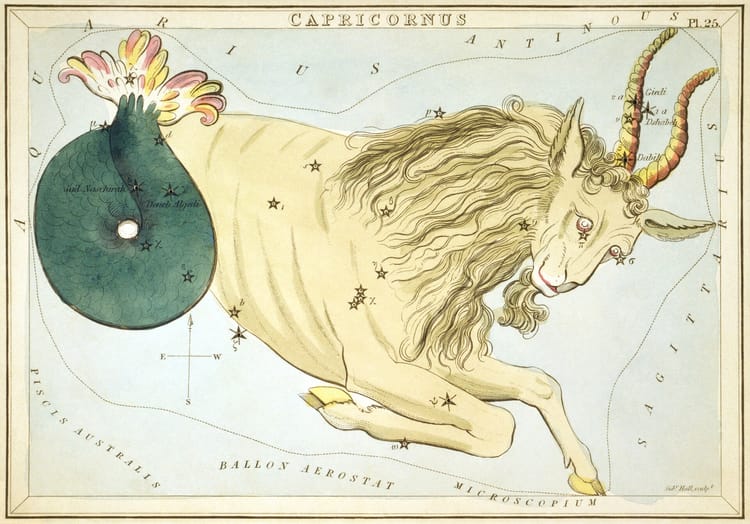

The spring equinox is almost upon those of us in the Northern Hemisphere. In some traditions this will be the New Year, such as on the Bahá'í calendar or with the Persian festival of Nowruz. It is also the resetting of the tropical zodiac as the sun (originally) passes from the 12th sign of Pisces back into the 1st sign of Aries. Even in the sidereal zodiac, which takes into account the Earth's axial precession, this equinox is a benchmark for precession calculations. And the sense of new beginnings is established indirectly within Western Christianity, given how there was a stretch of European history from 525 CE to the 1500s-1700s wherein March 25th, only a few days after the equinox, was the New Year.[1]

To me, there is certainly a kind of logic in marking the year's beginning now — the world seems to be waking up fully, and for any traditional astrologers it seems right to start the year with the symbolic "beginning sign" of the ram — but ultimately there is no more than in marking a new year on the spring equinox than at "the sun's rebirth" on the winter solstice. And for me, I find the most resonance in marking endings and beginnings together on the autumn equinox, a topic I'll come back to later. Let it suffice right now to say that as night becomes equal with day in autumn, a new cycle begins in the growing darkness; and by contrast, when day becomes equal with night, the spring equinox acts as the midpoint of the year.

For me it is the annual hinge, a great turning point where things are neither the root nor the branches, but the trunk spanning those mirrored halves. From this vantage we can look equally to the far past or the far future. It's a time to best cultivate a sense of the eternal present. To embrace transition, transmutation, liminality. Perhaps it's fitting that I continue to redefine my relationship to the spring equinox: it is such a protean, mercurial, wind-whipped time. Some years the day has meant hope and good possibility, and other years the day has sent me poison pills, wolves in sheep's clothing.

Like some people, I call this upcoming day Ostara. And in fact, as real as the day is to me, sometimes I call Ostara one of the most "fake" holidays on the Wheel of the Year because of how much misinformation about it floats through pagan and non-pagan discourse alike. How often have we all heard some story about the spring equinox being the feast of the Germanic goddess Ēostre (her old High German name being Ôstara) who ruled over springtime and dawn, and whose name as well as her motifs of hares and eggs were appropriated by Christianity for the holiday of Easter, itself calculated from the spring equinox[2]? The real story is much more complicated than that, which is to say: nobody even particularly knows the real story. The truth here is, like the holiday for me, ever-shifting and amorphous.

Here is what I understand to be true at the moment: the goddess Ēostre was documented c. 725 CE by the early historian Bede, who claims she was worshipped by the early pagan English during Ēosturmōnaþ (Ēostre-month, falling around April) and whose worship had since been replaced by Christian paschal, i.e. Eastertime, practices. Whether or not Bede is a perfectly reliable source, I see no reason not to personally take this claim of his at face value; she isn't presented as a figure meant for painting pagans in a bad light, and if he perhaps only heard insubstantiated rumors about Ēostre in his own time, those rumors still probably came from something real.

But unlike some other Germanic deities, today we have no information about Ēostre beyond that one reference. Her connection to spring is only assumed due to the season when Ēosturmōnaþ occurred; her connection to the dawn is a linguistic inference from how her name can be traced through other Indo-European words and roots for dawn and the east-rising sun. (And no, there's no demonstrable etymological connection between Ēostre and the Babylonian goddess Ishtar.) As for the goddess' connection with hares and eggs, this is pure 19th-20th century wishful thinking on account of the unexplained folk phenomenon in Germanic (and other) cultures featuring hares (or rabbits) and eggs as popular Easter motifs. Lastly, just like with the inaccurate Yule to Christmas pipeline, we have no proof of Church leaders enticing people into accepting Christianity by swapping Easter in for old spring equinox celebrations.

Now, having said all that because I can be frustrated by misinformation, let me turn back against pedantic rationalism. I still call the spring equinox Ostara for reasons beyond acknowledging the Wiccan framework in which I first developed any earth-based ritual practices. And despite the fact that the spring equinox's importance seems barely documented at all in the Celtic animist traditions from which I derive most of the pagan components of my rites, I do still "count" Ostara in my framing of the Wheel of the Year at all. For me, the spring equinox is worth observing in sheer principle, and there is at least some evidence to suggest that for pre-Christian Nordic peoples the sacrificial Dísablót festival might have fallen either on or close to that equinox[3]; given that I also incorporate Germanic animism into what I practice and given that the Wheel of the Year in its most well-established format also draws equally from Celtic and Germanic traditions, calling this upcoming holiday Dísablót doesn't seem out of the question. As I try to split my Germanic nomenclature syncretically between Nordic and English customs, I have pretty much bitten the bullet and embraced "Ostara" (or perhaps Ēostre, but the Old High German form is certainly easier for modern anglophones to pronounce and I already punish other people enough with the other holiday names I use).

And do I embrace hare or egg imagery on this day? I can't say I don't. Lagomorphs are vitally symbolic for me on the whole, a topic which eventually deserves its own post; and eggs are markedly potent symbols at this time of year (and delicious at all times). In my atheist upbringing, I didn't celebrate Easter as a child, and then when I was Catholic it didn't last long enough for me to enjoy more than a couple Easters either; but somehow nowadays I get an odd, self-aware little thrill at hare and egg folklore.

So there you have it — the most basic perspective by which I approach the spring equinox as a ritual holiday. But today I'm going to go one step further than simply positioning Ostara as the hinge-season, the time of transformations, the day of entangled lies and truths. We are still in the time of the Last Quarter, and I'm thinking about death work.

Death is not the end

Transformation is represented in tarot by several cards, but none more infamous than XIII: Death. When someone is first learning tarot, they're first warned that this card rarely portends literal death. It is supposed to mean metaphorical death, and therefore change. Movement from one state to another.

In trans lives, upon transitioning we often refer to the names we were born with as our deadnames; that part of ourselves is dead. (I do not personally follow that practice anymore, but I understand why so many do.) In end-of-life care, transition is also the word used for someone whose body is actively in the death process.

I think it's disingenuous at times to approach literal death as a matter of rebirth, because when something dies, all aspects of it are eventually destroyed except on a molecular level where its carbon-based organic matter is repurposed by other life. But one thing is for certain: if death is not necessarily rebirth, it is at least the kind of transmutation suggested above. Chemistry occurs. Magic occurs.

And the new life we see during springtime — regrowth — relies on the byproducts of death: decay. Thinking about death in spring is not at all incongruous. It's appropriate. Crucial.

Out of decay comes fertile soil. There can be dirt composed of little other than minerals, water, and trapped gases, but as soil it barely qualifies without raw life-bits broken down by decomposition. Hail to the nitrogenous proteins and their kin, hail to the fatty acids, hail to the sugars and cellulose and other carbohydrates — every portion of our diet becomes our flesh, and when this flesh is returned to the earth it joins the food chain again. I hold in awe the plants which grow from those nutrients' more elemental forms, but I likewise hold in awe the kinds of life that actively perform that transition into elements or into alternative compounds from how they began! Predatory or scavenging vertebrates, or the invertebrates like fly and beetle and mite and worm, or simple bacteria. And mushrooms, the very emblem of decay, as most fungi are saprobes: for their growth they are reliant specifically on nutrients from the decomposition process.

I've come to understand mushrooms as a phenomenon of late summer and autumn as leaves fall and decay where they lie, or as frequent rain induces rot on trees' bark or roots, and as increasing darkness furthers this process. Something like that. I'm not an expert on these kinds of things, just a worshipper. O the life begotten directly by death. O the mycorrhizal fungi that live in symbiosis with host plants, further improving the soil quality for the plants to thrive. The entire earth is encircled with networks of mycorrhizae. Maybe that particular connection isn't the stuff of decay, but it's at least more fungal magic so I can't help but think of it when considering decay eaters.

Some fungi are not the province of autumn. They are the harbingers of spring: morels. I have never seen a morel in person, never tasted them, and find their appearance trypophobically horrifying. Nevertheless, I've come to harbor a fascination. Why do morels grow in spring? Do they need even more moisture than other mushrooms, so do they wait for winter snow to saturate the ground more fully? Do they need autumn's decay to enter deeper phases? I don't know. I would like to find a morel one day just to contemplate its mysteries directly.

The morel apparently also holds the special trait of being pyrophilic. Not that it grows in fire, nothing does, but this mushroom genus is among other types of life that are the first to repopulate forests stripped bare by wildfires. Burnt wood sows ash in the soil, making it highly alkaline, but some plants and fungi love alkaline soil, morels among them. Here we find regrowth not just from decay but from sheer annihilation.

I meditate on such living things as these when I contemplate how to observe Ostara. Certain spring plants are well-established in my personal Ostara symbolism: pussy willow, crocus, and increasingly forsythia. I'll probably write about all of them later. But they are easiest to relate to as signs of life in spring. As the spring equinox carries death as life's roots, consider also the morel. Which, like even many other edible mushrooms, is itself poisonous. Cook it — transmute it — before consuming.

[1] March 25th was adopted as the New Year when the Anno Domini dating system was introduced. I wrote about the shifting New Year during my winter solstice post as well, but to review the salient parts here, January 1st started as the Roman New Year. In post-Roman Britain and other parts of Europe this custom was observed for many years wherein quite frankly nobody could agree on what year numbering to use; upon adopting Anno Domini, March 25th was chosen due to it being the Feast of the Annunciation, i.e. Mary's miraculous conception of Jesus. Throughout the medieval period and into the Renaissance, there were fluctuations about observing the New Year on one day or another, but many countries finally agreed on January 1st when they adopted the Gregorian calendar. Britain is a noted outlier; despite keeping January 1st as a deeply entrenched folk tradition, the peoples of at least England and Wales followed March 25th for actual year tracking from 525 to the reign of William the Conqueror, who switched things back to January 1st, and then in the year 1155 the British custom returned to March 25th and would persist across the whole island all the way until 1752 as the British clung to the Julian calendar longer than practically any other Western Christian culture.

[2] Strictly speaking, Easter is only calculated from the spring equinox in Western Christianity, governed by the calendar mandates of the Gregorian system. For Eastern Orthodox Christians who still use the Julian calendar today, they follow the old rule of calculating from a fixed date of March 21st (not from a specific astronomic event), which on their calendar happens to fall in early April for Gregorian-keepers. Depending on exactly when the moon becomes full in that time window, this is why Orthodox Christians sometimes celebrate Easter on the same day as Catholics and Protestants, and sometimes weeks later.

[3] Also perhaps at other times of year, but the point here is that the Norse — and perhaps their English and other Germanic cousins — may have been paying meaningfully closer attention to the spring equinox than the old Celts did.

Thanks for reading, and please enjoy your Ostara or anything else you might be observing on Monday! Next week I'm coming back to ordeal work, and the week after that will probably bring some much more in-depth spring hedgecraft thoughts.

Member discussion