Solar Summer + First Quarter: All work is work

Hello. It's a beautiful, sunny, dew-kissed Friday morning here, and this house's creeping phlox is blooming. That's the sign I now look for when Calan Mai is very close. Calan Mai means "the first day of May" in Welsh, so in keeping with my cultural ritual focuses that's what I call the day most of you reading would more likely know as Beltane or May Day, with Walpurgisnacht being the eve before.

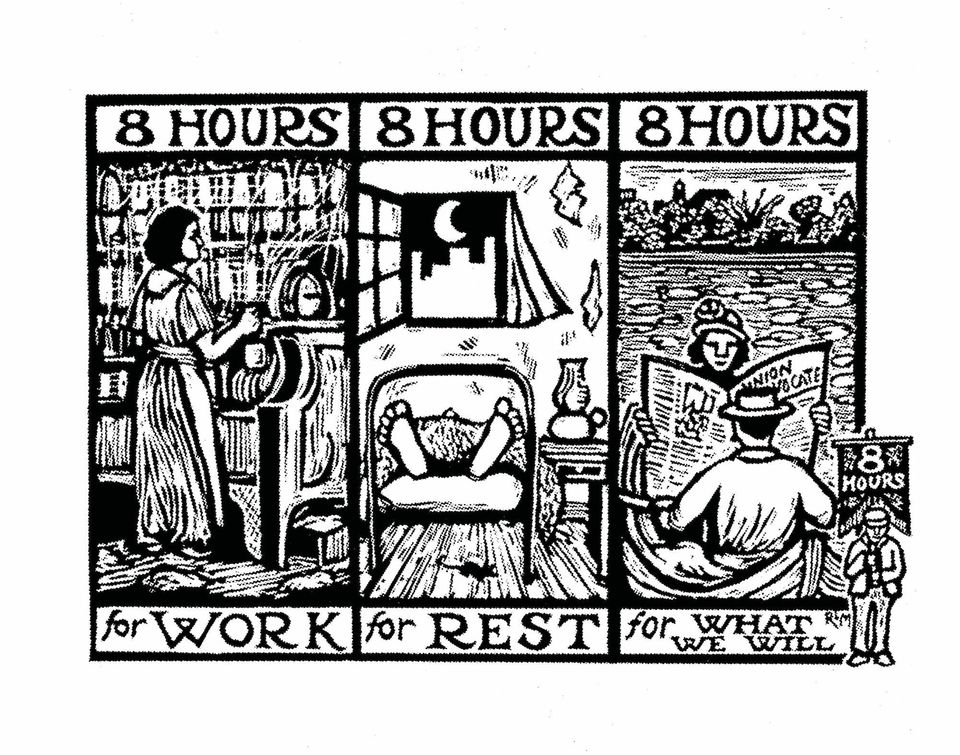

Next week for the Full Moon, I'm going to write a post for paid subscribers about the fertility rites and/or sacrificial rites associated with the holiday and with this time of year in general, and I'm expecting that sometime this year I still owe a post about the entire Wheel of the Year and what it means to me. But we're just now in the First Quarter today, and my reflections are about something very mundane but very important in its own way: work. Or labor. For more than a century, May 1st has been International Workers' Day, selected in 1889 by the Marxist International Socialist Congress to commemorate the USA's general strike that began on May 1, 1886 and was befouled by police violence in the Haymarket affair, for which several anarchists were then executed and became labor movement martyrs.

This may not be a political newsletter in the way many people think of it, and there are certainly some political topics I have no reason to delve into here, but I've never hidden the fact that I'm not merely critical of capitalism — that rather I hold a firmly leftist position in relation to it. If you try to sort me into a clearly delineated box within that starting area, that's where things do grow more complicated; I am or have ever been able to describe my views as eco-anarchism, anarcho-syndicalism, anarcho-communism, anarchism without adjectives, Marxism, anti-authoritarian communism, fully automated luxury communism, the abolition of money, etc., etc., etc. Lately, within all those options I've finally cemented some opinions about things that actually wouldn't work, but in most cases I continue to waver between "this would work fine if only we could overcome ___" or "this might not work perfectly but it's better than the status quo." Sometimes I'm just too pessimistic to see any hope at all, but even in those moments, it's rare that I can't see some way out that relies on some combination of all people controlling the means of production, all states as we understand them today being dismantled, and all colonized/industrialized communities shifting toward a re-indigenized/permacultural lifestyle.[1] I'm not going to spend this week defending those views; take them or leave them, just understand that this is the perspective I operate from in the rest of this post.

I want to now take the importance of International Workers' Day for granted and pivot to a problem that has dogged the labor movement forever — and that carries implications for my ritual ethic of sacred domesticity. It's the problem of domestic work as uncompensated work. Here is why I think the lack of compensation is a problem at all, and then why I think the lack of compensation occurs, what I think compensation ought to look like, and what revolutionary measures I'm wondering whether those of us who perform uncompensated domestic labor should be prepared to take. For anyone reading here who already spends a lot of time with feminist treatises, I'm probably not going to say anything utterly new here. But I still feel like with the upcoming holiday and with future domestically-focused posts assuming the unpaid nature of that work, I'm back to laying out a few principles. I'll do my best to make their connection to Salt for the Eclipse very clear.

I mostly just apologize in advance for the length of the footnotes.

Work that needs doing

Some kinds of work really don't need to be performed, either because the people performing that work are lucky enough to have another way to survive under capitalism (e.g. they have one job that pays them enough already and this other work is more like a hobby, or they have inherited wealth or a wealthy partner who can support them), or because the industries this work is in service to bring absolutely nothing of value to human society (e.g. stock brokers, defense contractors, cops). But most work does need to be performed, at the end of the day. Everywhere on the planet, most people hold the most convenient and reliable jobs they can manage to find[2], even when they aren't perfectly capable of performing the work involved, because capitalism as a global phenomenon demands that anyone who lacks capital and property to sell their labor and fork over their money to the people who do have it[3]...

... but most people also do work because a decent proportion of that work really does need to be accomplished by somebody. No, mass-manufacturing hundreds of thousands of plastic dolls, half of which will wind up in landfills because not enough people across the globe will be interested in buying them, is not terribly important, but a lot of other manufacturing is very important even if it might be time for some very hard conversations about the scale at which the manufacturing occurs. We need many manufactured goods, and we need farms, and we need someone to transport those things around (even if ideally the transit distance in question would be more localized). We need doctors, nurses, and teachers. We need people to build, operate, and repair utilities. We need people to build and make repairs in homes. We need people to keep our communities and surrounding environments free of litter, pollution, and pathogen vectors. Unlike some leftists, I would even argue that the hospitality industry (i.e. restaurants and hotels) is inherently necessary to account for basic food and shelter needs of travelers, people who have lost their homes (house fires and other disasters will still happen after capitalism), people who can't easily feed themselves — and also generally for helping large groups of people congregate in a social way — even if how a post-capitalist restaurant or hotel might operate wouldn't closely resemble the capitalist model.

That's only the tip of the iceberg, and I suspect that as these kinds of work already form the basis of well-known if not always well-paid jobs, I don't need to elaborate any further on this one front. Unsurprisingly, unions exist for a lot (though sadly not all) of these jobs, and some even still carry a bit of power in the US, because the work is so necessary that a strike by those workers has an immediate, intense impact. Lots of people do actually like and want to do this hard, tough work, because they want to help their communities, and their unions allow them to better do that work on their own terms instead of their bosses' terms.

But there are kinds of work that also produce an immediate material impact when they stop, but for which there are fewer unions, and for which capitalist society generally accords less respect or awareness. This includes therapists, in-home caregivers, online moderators, community facilitator figures, and too many other things to name. There are also kinds of work that may not produce a clear material impact, but that are still utterly necessary for making life worth living; and the workers here are likewise rarely taken seriously. The creators of art, games, festivals, and more are usually in this category. And beyond all this, there are kinds of work that ultimately satisfy very benign human desires but that are completely or selectively criminalized, such as sex work and psychoactive drug distribution; not everyone does these things out of obligation, and so we must imagine that in a post-capitalist society, some people would still choose to occupy themselves by offering others a sexual outlet or a steady source of, say, LSD.[4]

And then there is domestic work, which is to say, the main kind of work that people often don't even devalue as "lesser" or "inappropriate" work — because they forget that it is work.

The longer that I've performed domestic work as an adult, the more amazing this omission feels. Even qualifying it as a kind of "emotional labor" or "reproductive labor" is euphemistic in my eyes: just call it work! It is work! You, or someone in your household, has to do various chores on a daily, weekly, monthly, or annual basis. Generally for me it averages to at least 5 hours a week, and I'm not even doing all the chores, nor are my owner and I always doing all the things we could or should be doing. If you don't at least do the bare minimum, you're going to wind up with serious sanitation problems (including heightened risk of pest infestation) in your home, you're going to feel physically and psychologically uncomfortable, you're going to find it harder and harder to accomplish anything as a chaotic mess presses in around you, you're going to waste money buying new clothes or disposable dishes instead of just cleaning what you already have, and so forth. And in fact, when you can't or don't want to clean your clothes, your dishes, sweep things up, tidy a room, you can literally hire other people to do it. They can get paid for it! Why aren't you paid if you do it for yourself and your household? Well, I'm getting to that in the next section, but the reason itself has no bearing on the absurdity of these circumstances. And all of this is to say nothing of how astronomically the workload increases if you have at least one child to take care of.

Under capitalism, where time is money, doing domestic work as often as it needs doing can take so much time that it severely interferes with doing the kind of work you get paid for. If you choose to do non-domestic work less in order to handle domestic work more, then you will simply not earn very much money anymore. The reformist measure of a Universal Basic Income should really be called "finally paying people to do domestic chores," and it should be a greater amount of money than what's usually proposed.[5] In a post-capitalist society — which would hopefully be post-money as well — I can't say we'd automatically be talking about "paying" anyone for domestic work, but domestic work would still need to be accounted for as a component of communal labor architecture; in any economic system, domestic work has to happen. All work is work. It should be treated accordingly.

Why have modern societies massively failed to compensate domestic work?

The answer to this question lies in how I just said modern societies. The fact of the matter is that although the gendered divide of most domestic work as "women's work" pre-dates capitalism, nothing I've ever read about pre-capitalist or for that matter pre-industrial society has suggested that domestic work has ever been as completely, categorically devalued as it is — until relatively recently. Before most people had to work for wages, domestic-and-therefore-women's work was certainly denigrated in particular contexts, but it was a foregone conclusion that this work was vital to the functioning of communities, and that it would be compensated by dint of how communal resources were distributed differently than they are today anyway. If you were a woman, then of course you would generally take part in the domestic work of your household, and of course this would be balanced by men doing other sorts of work. This applied whether you were in a higher or a lower social tier, even if the "lowest" domestic work might still be delegated to servants (mostly female, but not completely) rather than expect a noblewoman to scrub her own pots; she would still have to manage the domestic work and even still perform some of it herself, including fiber arts.

This ethos carried into capitalism for a while. The archetypal Victorian housewife was "the angel of the house," and the wealthier she was, the less work she actually had to do, but her work was perceived as solidly domestic in nature regardless. The less wealthy women did have to choose work besides domestic work, such as in the mechanized garment industry, but working outside the home was still more likely for single mothers or particularly marginalized women; even right into the 1950s and a bit beyond it, a generally working-class woman's role was at least idealized as performing domestic work, with her husband making enough money to support her, himself, and any kids they had.

Over time, more and more women have rightly spoken up about how actually, they would like to do more types of work than domestic work. More and more people in general have made strides at uncoupling domestic work from "women's work," too — homemaking husbands, homemaking men, they're on the rise. All of these social improvements are good. I'd be the last person to say it was a mistake for anyone to demand such changes. However, to adopt these improvements and to not simultaneously demand an end to capitalism and wage labor — that's the real disaster. Now we're stuck in uniquely untenable conditions. The heterosexual nuclear family was already an unnatural way of "formatting" households compared to the extended networks that humans originally evolved to rely on; but once these paired husbands and wives both entered the non-domestic workforce together, bosses saw no need to pay anyone extra to account for the monetary and temporal cost of having kids, and both husband and wife still need to work at least 8 hours apiece outside the home (or, in the age of remote work, on non-home tasks, at home) to have even a prayer of making ends meet. This leaves domestic work itself floating as a nebulous timesuck to be dealt with if and when either partner has the energy after already working so hard 5+ other days that week, or if and when you want to waste precious weekend leisure hours. Good luck if you don't have a partner or roommate at all.

And of course, due to lingering stereotypes, women (or anyone who's not strongly male-aligned) are usually still the people who pick up the domestic work when they can. I don't find it surprising in the least that the conservative tradwife movement is so appealing for some women today. It's certainly patriarchal and usually loaded with a lot of deeply fascist implications, so that's why I don't subscribe to it, but I viscerally understand why tradwives are a much talked about trend. Domestic work is enough work — especially, again, when parenting is in the mix — that if it's more personally fulfilling to someone than work outside the home anyway, why wouldn't they hope to maximize their time spent doing that, and not trying to work elsewhere? Why wouldn't they enjoy being financially supported by someone else since they themselves are not going to get any money for taking care of the home? The problem is not people choosing to do domestic work instead of having a "career"; the problem is people framing this choice with reactionary gender politics. I myself like doing certain non-domestic work enough that nowadays I don't necessarily harbor dreams of being exclusively a full-time homemaker, but doing about 50/50 domestic work vs. non-domestic work is still pretty appealing.

A lot of adults my age and younger claim that they're not very good at "adulting," and by that they usually mean taking care of things to do with their household. Well, of course we can't be good at that if we barely have time to do those things anyway.

Uncompensated domestic work is uncompensated because yes, for thousands of years domestic work was patriarchally devalued to begin with, but it's taken only a couple centuries, and especially just the past few decades, to create a "career"-oriented work ethic wherein there isn't even any room for domestic work to exist, unless your career is still as an actual maid, nanny, au pair, and so on. Naturally, those jobs are also ludicrously underpaid right now, and in keeping with historical precedents, those jobs are often held by women of color and/or migrant women who already have more economically precarious lives.

What is a better way & what must we do?

I don't have a complete plan in mind for how to compensate domestic work in a meaningful way today. This is the point at which what I feel like I know for certain gives way to more open-ended reflections. For one thing, there must be some diversity of approaches here. I imagine we must equally:

- Redouble organized labor efforts to control the means of production[6] and thus end capitalism

- In the interim, especially if the above is a doomed dream, at least form homemakers' unions and plan direct actions to demand income from the state

- Support Universal Basic Income policies where applicable

- Continue education and encouragement around domestic work being a non-genderable activity

- Simultaneously continue recognizing that because most domestic work is still performed by women, this is a feminist issue

But as established in the past, I am really not optimistic enough about the current state of things to just speculate on ideal courses of action. The world we grew up in is in eclipse. We do not know how long totality will last once it sets in, and we do not know what will happen in that un-light, and we do not know how the world will look afterward. Perhaps we should still try to do all the things listed above, because there's no good reason not to try them, but those efforts alone don't seem sufficient.

I suspect we must also try to just prefigure and practice, as best we can, however we ourselves might like domestic work to be performed and compensated amid the ashes of collapse. I don't mean just unthinkingly mirroring the tradwives, and I don't mean adopting lifestyle activism as a means of virtue signaling and self-congratulation. I mean rather that a different, not necessarily better world is about to arrive in front of us whether we like it or not, and that although we may not even have control over what lifestyle to adopt in that world, if I assume we'll have any control at all, then I'd like to think ahead.

What is the best way to imagine my domestic work taking place even under potentially more unstable, more impoverished, less financially compensated conditions? What is my domestic work utopia, and what are its more pragmatic variants?

My answer in any of those framings might be the same. I want the work understood not only as work, but as sacred.

To serve the home is not a matter of gender, but of calling. It's no different than that of a monk or a nun, though of course with a little less celibacy involved.

In our homes, we rest and feel safer, we dream our greatest dreams (whether in sleep or in waking), we eat many of our meals, we try new hobbies, we have sex with other people or with ourselves, we heal from all but the worst illnesses, we stay protected from extreme weather — or we should be able to. Whether our homes are stationary or nomadically carried, there is no other place to do all of these things so steadily and often. That is what makes home home. To truly have no home is an existential, cataclysmic tragedy; to deny someone their home is an indescribable injustice. We used to be born into our homes, and we used to die in our homes, and in some cultures this still happens. When we are children, home is where we learn our earliest lessons, and the lessons don't stop when we go to school, and for some of us school even happens at home. When we are children, home is where at least one parent is, or it should be, and no matter how frightening the world outside might feel, there should always, always be home to return to, to your family's warm, loving embrace.

With so many vital parts of life happening there, the home is sacred, and so to care for the home is to also undertake a sacred duty. How many animist faiths have gods or spirits of the home? Many. Perhaps most. They're not a part of my own cosmology, but as a witch — especially as one drawn to kitchen witchcraft, and as a witch who needs an indoor "base of operations" for hedgecraft activities — I can't help but feel driven to include the rhythms of the home among my other rhythms. Domestic work is a daily, weekly, monthly, annual rite, unending and circular and cyclical, infinite. It may not be strictly "a woman's work," but as the saying goes, that work is never done, and although we might interpret that to negatively mean that homemakers work too much, positively we might also consider that as house chores never stop needing to be done, they mirror seasonal living and they remind us that time is a wheel, not a line.

In a sense, I don't even want to be compensated for this work. I am already splitting it rather fairly with my owner; if I might do a little bit more of it at times, that still feels fair because he does other work that, while admittedly being work that's more often gendered as male, it's mostly work that I would not like to do myself, such as car repairs or carpentry. So on a personal level, I don't feel owed anything. I would like our whole household to be have more money, but that's as much for how I'm underpaid in my day job as it is for how we both take care of the home — and what would I really ask of the state? Pay me to routinely sanctify the home that I hope you will never enter? That would be entertaining, but it's hard for my mind and heart not to leap ahead to a post-capitalist context. Sometimes they leap in the hope for getting to wake up in a beautiful and abundant world where I begin my day with breakfast, then homemaking and gardening for a few hours, turn to my latest public-intended creative project for another few hours, then eat lunch and spend the rest of my afternoon and evening with whatever else seems necessary or worthwhile, including any requisite lunar or solar rituals. Sometimes my mind and heart leap ahead to thoughts of how to survive amid scarcity, though — and here the sanctity of the domestic still reigns. Indeed, under such conditions there might be times where domestic work is not only the most important thing for me to do, but the only thing I have time to do at all.

On that note, in keeping with my body's habit for this time of year, I'm facing the onset of a migraine, and so I should end here; but if it's a little abrupt, I don't think it's inconclusive. I'm content with these thoughts as they are. On any upcoming May Day celebrations, if you honor workers of the world, please include domestic work in your reckonings, and I will be doing the same. All work is work.

[1] The only terms I steadfastly avoid for my flavor of leftism are "socialism" (too vague at this point and often conflated with making certain concessions to the left like universal healthcare but without actually ending capitalism) and "Marxism-Leninism," "Stalinism," or "Maoism" (usually inaccurate to what I believe, and associated with state regimes I don't support, not even just because of what those regimes did, but because they are state regimes).

[2] Assuming they aren't forced into something they'd rather not even do, whether through outright trafficking, debt peonage, or similar forms of heightened exploitation.

[3] Bosses (business owners, executives, board members, and other upper management) and landlords rarely perform work, and if they do (and remember that landlords will usually contract or retain someone else for repairs), it's inessential to their survival. All work is a hobby to them because they can do absolutely nothing all day and they will still profit off of whatever other people are doing for them or directly paying to them. Yes, they may make decisions that completely sink their ability to turn a profit in the future. But except in very small business owners' cases, the closure of a business has minimal to no impact on a boss' personal survival, and in all likelihood they will still recover their capital when declaring bankruptcy and move on to start something else or live comfortably off of a golden parachute; likewise, landlordism is a completely parasitic, predatory behavior, and if anyone does manage to lose enough of their rental properties to the extent it impacts their livelihood, then all I can say is that it sucks to suck.

[4] I am never going to debate sex workers' rights on the job or their rights to choose that job in the first place. I do understand why someone might say, "But is that work really necessary in a post-capitalist society? People don't need sex to stay alive, and communities don't specially benefit from having people to have sex with who aren't your dedicated partner." However, even to this I would ask: are you sure about that? I'm not sure about that at all. Ask any sex worker about the ways they benefit their communities, and at least some of the ones whose voices I've listened to have a whole list of ways they've discovered. And besides, even if sex work were completely "frivolous," well, you're never going to successfully legislate to stop people from selling sex, or for that matter from "giving it away," as an occupation. In a post-capitalist society some people will still center sex in the work they perform, other people will be interested in receiving those services, and you might as well manage your community with that in mind. I believe this entire argument can also be extended to most recreational drug use as well, with the two exceptions being the highly addictive, highly dangerous examples of opioids and processed cocaine (vs. raw coca leaves); in those cases I am still too anti-carceral to support criminalization, but I would at least agree with anyone arguing that communities should implement various measures to intentionally reduce people's likelihood of becoming dependent on those substances.

[5] It should but does not always go without saying that I don't believe an ideal society is one in which "everyone works." Just as there will always be some work that needs doing, there will also always be people who literally cannot work, or who can perform some types of work but ought to always be considered exempt form other kinds. So although I am saying a lot in this post about work and how to compensate it, please remember that because having one's human rights respected shouldn't be contingent on working, I see permanently non-working people as comrades in labor struggle from that angle. "Work that needs doing" is always a matter of work to perform for communal benefit, not work to individually perform for justifying existence. In light of all this, UBI proposals are also very reasonable from the perspective of paying people who can't work, not just paying previously uncompensated domestic work.

[6] In the past and present I've generally supported the anarcho-syndicalist idea of a national or global general strike to accomplish these ends. This is not a completely nonviolent approach as some violent defense tactics would become necessary, but at the end of the day, if a critical mass of people struck and demanded ownership of their own workplaces, there would be too many of us for all the armies in the world to terrorize into submission; and in using the general strike, we would be less likely to send the labor movement in authoritarian directions (or to just fail outright) than if we simply used a violent offensive as has been undertaken in the past. Now, as for whether I think a general strike is what's most likely to happen, I will refer you back up to the skepticism in what follows after the bullet points that included this footnote.

Thanks for reading. I have a busy holiday weekend ahead of me and I hope that if you're a fellow observer that you also have good things planned. As mentioned, I will have more holiday-adjacent ritual thoughts for paid subscribers next Friday. After that, things will turn rather introspective as I do a Last Quarter mental health check-in of sorts — and it might actually not be gloomy there. Sumer is icumen in!

Member discussion