Full Moon: The rite of writing

Hello. It's Friday, and in the month that just ended, I made some progress on my next novel. Not for National Novel Writing Month, but just as an ordinary month: I've been working in some form on the same new novel since 2017, and it will be extremely long by the time its first draft is complete.

There are a number of reasons why it needs to be so long, but as grueling as the process is, I feel undaunted. I've been chipping away at this project without complaint, and will keep doing so for at least the next couple years, considering remaining drafting time and estimate revision requirements. While I need to hide nearly all details about it in this post since the book is being written under my professional identity — and indeed, the entire authorship situation is a bit more complex than I can describe here — it gives nothing away for me to say that my stubbornness derives from a conviction that I must write this thing. This is because:

- The text concerns many matters that are of absolute importance to me, more than most other stories I could possibly write.

- More specifically, the text is of overriding (spi)ritual significance, with most of my religious, cultural, and ecological focuses linked all together.

At the risk of pretension, for a while I've been considering it my Great Work, the magnum opus of alchemy given literary form. Rightfully, I should have waited to start this book until I had published more things already; I have certainly published some things, but despite being in the middle of my 30s I would still, like so many writers in such a pinched market, be classified as "emerging." Nonetheless, I have my reasons for proceeding; and as the Full Moon governs matters of art for me, this week I'm going to explain my choice. Even obscuring the novel's material, I'd like to reflect on how the choice to prioritize such a massive undertaking has shown me deep implications for not only a healthier "art world" but also a large, grounding, necessary facet of my witchcraft.

Death work, spirit work

This novel's importance intersects with my developing practices around death work and apocalyptic witchcraft — not only in thematic focus, but in external practicalities. I began writing it while already more-than-moderately aware of the worsening existential risks to humankind and potentially to most current forms of life; in the years since, my fears have deepened that although I will presumably live long enough to finish and share this one work, I may not live long enough to write too many other things. My family tends to live into their 80s or 90s, but even if I never develop any inherently terminal health conditions, there's an ever-heightening chance that by my 50s or even sooner I could be cut short by some extreme weather event, a worse zoonotic disease than covid, a famine, political violence in the course of civilizational collapse, or generally being unable to afford or find a lifesaving service that I once took for granted.

I don't think any of the above are guarantees, either; I've resigned myself to nothing. But just as it's good practice to write out a will, an advanced medical directive, and an overall death plan as aspects of ordinary death-preparedness, likewise I am hoping not to leave creative and ritual loose ends. I would be a fool not to write this novel while I still can. I would die in grief. I have no time. I must do this. Anything other fiction that I'm able to write afterward will be the proverbial gravy.[1]

Besides those more grim calculations, there's also the matter of spiritual possession. Of course I would like to be able to support myself through writing, which in fiction's case I would best pursue by writing some much shorter, more marketable stories instead of spending so much time on the magnum opus; nevertheless, even leaving aside the sword of Damocles that hangs over my ability to write anything at all, I can tell that further publication-worthy creative writing is going to stay rather stymied until I've expelled this one story from myself. It doesn't help that being autistic makes it hard for me to easily move my attention[2], and it helps even less that I have limited hours in a week to spend on different projects — mostly, however, neurodivergence and capitalism aren't sufficient explanations for my priorities here. This novel has become one of those phases of my life wherein a creative work is consuming my attention so vastly beyond anything else that it makes better sense to say the work has possessed me. I must exorcise more than one million words that are controlling me.

I won't let myself die before the Great Work is complete, and until that completion I also won't be able to live as freely as I could. So I have made my choice.

Pure offerings

Considering the above: in writing the Great Work, or other nearly-as-sacred things that have come before, or perchance any things that will come later, writing of this kind cannot be compromised. Compromise takes many forms, so while I write these things immersively, I remain watchful.

The voice of the writing must be exactly what the work demands, not simply what could appeal to a certain audience. This doesn't mean launching my language into insultingly obscure phrasing and postmodern masturbation, but it does mean the literary equivalent of sculpting out a shape that already lies within the rock, rather than imposing a shape upon it.

The effort in the writing must be serious. I can and ought to laugh at some pieces as I go, but this is not a hobby to "fit in" around other activities. Other activities are fit in around this. Only a few equally sacred tasks merit equal priority, and even my day job doesn't qualify; that is to say that like any good anarchist, I work to the minimum degree expected by my boss and then, as this leaves me inevitably with free time during work hours, I joyously commit time theft. None of this means I neglect relationships or the most important chores, because I wouldn't survive very long if I ignored those things; but when confronted with so-called leisure hours each day, my aim is to spend at least a couple of them writing a little of the work. There is no specific word count to aim for, and yet when writing time is made I am committed to doing it, allowing most distractions to break up my pace for only a few minutes at a time. I am wasting my own time at a screen[3] if I incur eyestrain for something less valuable than writing.

The last time I worked on something in this manner, it wasn't the same kind of writing, but it was my household's grimoire. I didn't sit down with it multiple times a week, but about once a week I made sure to do so, relentless and methodical, starting with the calligrapy and ending with the illustration. It took years and it overlapped with the start of this novel. Now I do not write a grimoire, but it is still the word of life and words offered unto life. I've felt like a monk sworn to the act. A satanic monk? Perhaps beyond the binary of the Devil and the Authority — something wholly itself and inexplicable outside itself.

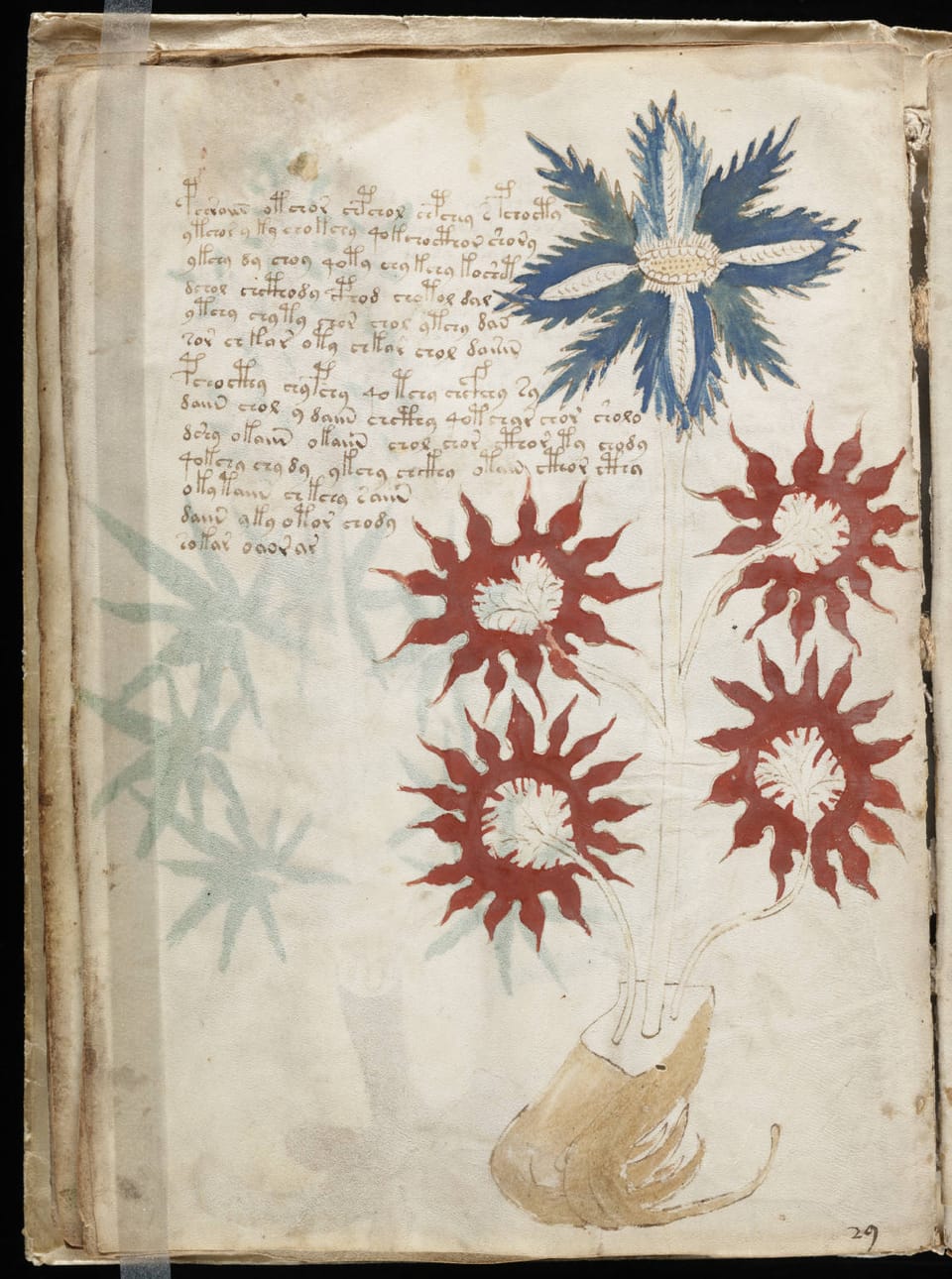

The Voynich manuscript comes to mind. No one today has yet translated the language it was written in, or even whether it's its own language or a cipher for another one; so we do not know what the book is about, although there are dozens of hypotheses based on the accompanying art and where the text may have originated. I think it is about plants and seasons and good things like that, in some way, but the rest is an exquisite mystery, uncompromised by others' interpretation.

Sacrifice & submission

There are things I've given up by writing the Great Work so incessantly. I could, again, be writing much more rapidly and easily published things, maybe earning more as a result.

I could also exercise more — which is not to say I'm not exercising at all, but I could really throw myself into it without this.

I could cook more food for myself. Already a challenge, made harder by writing.

I could go out more, garden more, quicken my relationship to the land and sky, connect faster and deeper, learn more things to help me forage and hunt. I've certainly been trying, but I can't give it my all as some people do.

I could watch more things that I care about watching, and read more books, and go to more live music events.

I could devote more time and thought to community growth within the overlap of kink and rite.

I could work on more art that isn't writing; I could start creating my own tarot deck, or accelerate my knitting skills, or take my instruments out of storage and make music again, or a few other things I've had in my mind; all these things shall come to pass with time, but the Great Work takes me first. And even when it's finished, I know that what shall happen afterward is what always happens: no matter what other creation is receiving my energy, I am always writing something in the background. To write is a rite even without writing anything of importance.

I'm not good at patience, but by delaying so many of the above things, I have learned some patience ironically through engaging my monotropism. I am working on the thing I must do now. I am not wasting time. I am making. It is all right for many other parts of my life to wait. Not all parts, but those ones.

There are also other things that I've been learning to be glad of losing. The more I push myself to write, the more I rid myself of dross: social media ouroboroi, useless news, vampirically unilateral conversations. Is it still a sacrifice if I do so in celebration? On this most recent Calan Gaeaf, I vowed as usual to abandon things which do not serve rite, and I also more sharply specified that I would jettison using one social media account between certain hours, and checking the news at all. I made those choices partly for my own well-being, but also to have less distractions from writing. Less distractions flung by the great dung ball.

I know many people who are struggling to more frequently practice their rites or their arts. To them, I can't proselytize as the Christians would, but there is a kernel of truth in demanding surrender to their god's commands; the problem is not the commands more than the surrender itself. Those of us who submit, in kink or in ritual or both, are familiar with the experience of discovering freedom in not living as lonely islands. So I say: if rite calls you, submit, and if art calls you, submit. Make the space for it, and do not only leave your practice there to visit when you have the time; dwell in the space you made, and venture out when needed. As for the app that distracts and infuriates you the most, delete it. Our true gods, spirits, ancestors, egregores, fairies, and fetishes, whatever and wherever they live, deserve all of us.

[1] Undoubtedly my internal calling to write Salt for the Eclipse is the non-fiction parallel here.

[2] I've been reminded recently of the monotropism theory of autism, which highly resonates with my experience and which I strongly encourage other autistic people or curious supporters to learn about.

[3] I would love to write on paper again, but for writing of some length I'm more than happy to take advantage of a keyboard, and as the Great Work is actually collaborative in nature I need the data-sharing afforded by telecommunications.

Many thanks for reading. In the spirit of having my writing supported, I would be remiss this week if I didn't humbly ask for some readers who have been free-reading to consider subscribing at a paid tier, the lowest tier being only $1/month. Either way, next week there is going to be a heavy, no doubt lengthy post about violence, and the week after that will be my first post written exclusively for the Occult tier ($5/month).

Member discussion