First Quarter: The witch's art of dyeing

Hello. It's Friday, and the greening here is nearly finished. Most of the spring flowers have dropped and given way to leaves, with exceptions being plants like honeysuckle, creeping phlox, and some of our azaleas. The things that will bloom in summer are still pushing up from the ground. We are finding bird nests with eggs in them, and sometimes brooding mothers. The weather is such that a rainy day is pleasant and gentle, and a sunny day might be getting a bit too warm but can also be unfathomably beautiful. The Pleiades are hiding. And in a rare, rare gift, not very typical for this season or any season, hours after last week's post I was lucky enough to see the Northern Lights from my house.

I have continued to have my bodily struggles, and the world remains subtly out of balance, but the merry month of May always seems to call loudly to the portion of my rites belonging to the green witch, the woods witch, the hedge witch, the witch who lives and works mostly alone but has an explosion of abundance right within reach. I increasingly think that it's of the utmost importance for ritualists to work relationally rather than to think of themselves as "solitary" — we must resist atomizing, isolationist impulses in this time when so many broken bonds must be rewoven — but the fact remains that to engage with witchcraft as a specific ritual format, I see an intrinsic component of self-reliance in the sense of a single human operating effectively within an enormous more-than-human network. This is partly rooted in many witches taking liminal, borderland roles in human society while serving as a bridge to places beyond; hence also how, much like other magical/religious figures in a plethora of pre-modern cultural contexts, identification as a witch can be particularly common for gender or sexual outsiders, or for neurodivergent people. In any case, this mode of witchcraft can produce consequences like needing to depend less on other humans than most humans do, and thus to depend more on the birds and beasts, flora and fungi.

Though this could seem like the prologue to a new post about foraging, herbalism, or my forays into a better understanding of my micro-bioregion, for this First Quarter week I'm actually considering a different angle on the earth's gifts to a witch. More in the vein of hand crafts, I'm thinking about how the archetypal self-reliant witch is an expert worker of wool — and other natural fibers, but wool comes to mind in this season as the sheep would now be sheared — from the initial processing to the spinning to the weaving or knitting... and the dyeing that happens somewhere in between.

I have spent most of my life being absolutely fascinated by traditional hand dyeing techniques. Arguably half the reason I've finally spent my mid-30s diving into fiber arts is to have a context to learn dyeing. I haven't tried this art form yet at all, but I keep telling myself that once I can invest in a spindle, then I'll have an excuse to acquire either raw or washed but unspun wool, and then once I get comfortable processing or spinning the wool I can start making small batches of wool in colors according to old, old methods.

I don't even have a spindle yet, but I can start by writing here — reflecting on exactly why I would like to become a hand-dyer in the first place, and what I abstractly know about the practice, and where I can see all of this taking me.

Juniper

One of my first exposures to any concept of witchcraft was a short children's/YA novel I wound up with at age nine. The book was called Juniper (also alternately titled A Year and a Day) and what I didn't know when I first read it was that this was a prequel to another book, Wise Child; the Juniper in question was a witch-like (or cunning-like) woman, with the original book showing her through the eyes of a girl apprenticed to her, and the prequel showing Juniper's origin story in the first person. My earliest attachment to this character was almost phonetic, a fondness for the word juniper that has remained with me, but there's much more to the story than that.

Both books were written by the English author Monica Furlong. I don't know a great deal about her, although later in life I've been able to glean things like her journalism for publications that I don't have a high political opinion of, even if their lenses might have shifted slightly between now and the decades when she wrote. I've also gathered she was rather heavily connected to the Anglican Church, albeit in a reformist capacity and with an obvious interest in mystic spirituality. Taken altogether, I can't say what I would or should think about her as a person, and I can neither endorse nor condemn any of her non-children's output. I especially have no idea how much any of the magical cosmology she put in Wise Child or Juniper was based on her involvement in or awareness of any modern-day pagan/occult traditions and what they claim to have inherited from the deep past. Never mind what Furlong's grounding was in more concrete history. Hell, I don't even remember exactly where the books are set, only that they are pre-modern, probably medieval, maybe based in Cornwall and/or Scotland. I need to reread with adult eyes and knowledge.

Furlong did apparently drop acid, though, which would explain the vividly psychedelic "flying ointment" sequences in these books. And though the setting context now escapes me, I loved the narratives and characters to death, especially those of Juniper itself. Although I also enjoyed Ursula K. Le Guin's Earthsea books, which are more of the conceptual forerunner of something like Harry Potter, I would say that Furlong's little diptych[1] created more of my Harry Potter moment vis à vis offering me a magic-using protagonist for me to identify with, both in her forms as an impertinent girl and an independent woman — and likewise offering me a childhood sense of what magic, especially witchcraft, is about. If Furlong herself was anything remotely as reactionary as J. K. Rowling's true colors (or if she could have been a spiritual parallel to Marion Zimmer Bradley[2, with a blanket content warning]), then well, all the more reason for me to continue seeing Mother Ursula as my true role model in this fantasy subgenre. However, Juniper the witch, or Juniper the doran to use the novel's terminology, she will also always stay with me.

She will stay with me because in her youth as shown in the prequel, she is given a very well-worn but well-told tale of being born to privilege but having to unlearn it. She is a headstrong princess who chooses to be apprenticed to an esteemed doran because she has glamorous ideas about what magic involves, and her spirit is not broken but gradually transmuted through hard, hard, hard initiatory work, which often involves doing things that she first finds extraordinarily tedious and non-magical but that her teacher — a sharp, no-nonsense woman named Euny — insists upon to bring Juniper into better relation with the ordinary world, yanking her wholesale out of the proverbial ivory tower. Juniper often thinks she's only learning how to live a miserable existence, consigned to drudgery, however she's really learning things that are vital to the animist principles underlying the book's magical system. She learns the rhythms of the seasons and her locality, she learns meditative skills, she learns to accept manual labor instead of ordering servants about, and she learns the need to occasionally take life in a remarkably visceral scene where Euny tasks her with slaughtering their pig. If you've been reading this newsletter for a while, I'm sure you can see how some of these elements have lingered in my own approach to witchery.

Eventually, of course, Juniper does start to take more pleasure in her studies, partly through the assistance of another doran, Angharad, who is far more amiable than Euny; and Juniper does start to learn more visibly magical practices. There's a flying ointment sequence as indicated above, and there's also a point at which Juniper is tasked with weaving herself a cloak of special significance. This cloak is meant to be worn only by a full-fledged doran, perhaps echoing the white coat of a doctor or (for a more pop culture symbol) the lightsaber construction ritual of a Jedi. The colors of the cloak must also be chosen very carefully as they will, if I recall correctly, represent various aspects of the individual doran's magical strengths and essence. I also seem to recall that the colors of the cloak Juniper ultimately weaves herself are not the same colors as what she wears as a much older adult in Wise Child, which suggests that in this magical tradition some fluidity is allowed; but what I recall most vividly is how Juniper agonizes over which wool colors to choose, and how prior to being given this task she has already learned how to dye wool.

The narrative describes a number of pre-industrial dyes and mordants, and those substances and their ritual function have lodged in my mind ever since. I've never thought too seriously about weaving my own ritual cloak, but it's not out of the question; and just as most English speakers instinctively associate witchcraft with bubbling cauldrons, bunches of herbs, and broomsticks, I think I will never shake the idea that a full-fledged witch must partly be a fiber artist who doesn't just make garments from scratch, but who also designs and chooses their colors with symbolic attention.

Obviously my subjective ideas of what a witch is are not a mandate, especially not when one idea comes from an increasingly obscure children's book by a writer whose personal background in witchcraft, animism, paganism, occultism, or anything similar is rather unclear. Nevertheless, I am glad that I was exposed early to some fictitious ritual hand-dyeing and magical color theory, because it's aligned with my strong sense of aesthetics in ritual spaces and ritual living. It isn't enough to conduct a rite with tools that are functionally capable; the tools need to be appealing, even if what's attractive to one practitioner is not what will be attractive to another. It isn't enough to make things like clothing from the gifts of the earth like wool, linen, or silk, in order to simply bring protection from the elements; the clothing deserves to be beautiful, showing the love between the crafter and the crafted, and there are also practical implications for choosing a color that will catch the eye vs. allow for camouflage. I even recently heard the argument that our ability to recognize beauty has evolved because witnessing beauty is the ultimate reason to bother staying alive despite life's travails. I couldn't agree more.

Dyes & mordants

What makes traditional dyeing "traditional" is not just that it's done without industrial equipment, but that the substances involved can be derived rather directly (though not always simply or cheaply) from flora and fauna, as our ancestors knew how to do for tens of thousands of years. This would once have meant that useable materials varied by geography and narrow trade corridors, creating bioregional dye cultures in parallel with dietary culture and medicinal culture. Nowadays of course many hand-dyers use substances they would have previously struggled to ever obtain, but I'll come back to this point later. Regardless of the specific options available for hand-dyeing, it's also usually been the case that most pigments can be achieved by some means or another in most parts of the world; the cultural variation that arises is less like a community never having the means to create a purple shade, and more like the local rarity of purple-making materials causing that culture to turn purple into a high-status pigments reserved for just a few contexts.[3]

I am not yet versed in all the ins and outs of traditional Celtic, Germanic, or Ashkenazi hand-dyeing materials, the things my ancestors would have encountered for centuries if not millennia. And admittedly, though connected ancestral practices matter very much to me, I'm already working in a syncretic, colonial, creolizing geography where the natural dyes that are most available to me are not the same as those of a 15th century Cymric cunning woman, for example. It's rather like how although I keep haphazardly stepping into kitchen witchcraft and have an interest in ancestral recipes, those are not the only things I cook. Learning about dyeing materials, I've cast a broad-ish net. Here, then, are some of the materials that have most attracted my curiosity over the years.

First, the dyestuffs themselves. These supply the pigments.

- Madder: One of a few plants in the Rubia genus found and used across Eurasia. Their flowers and leaves look unassuming, but the roots are very large and contain the compound alizarin.

- Cochineal/carmine: An ancient dye in the Americas, derived from cochineal insects who contain carminic acid as a predator deterrent. Its brilliant red became attractive to European colonizers who had formerly relied on madder or on kermes (another insect).

- Saffron: The threads of the saffron crocus, creating orange or yellow depending on other substances used. Notably expensive due to how laborious the crocuses are to harvest and how few threads are produced for each flower. Native to central and west Asia, and/or eastern Europe.

- Curcumin Another beautiful orange or yellow dye, and like saffron it's also from a popular spice: turmeric rhizomes. As such the dye has its origins in the Indian subcontinent and southeast Asia.

- Weld: One old name for Reseda luteola, a common "weed" that contains an abundance of luteolin, which makes a very bright yellow. Weld may be one of the oldest dyes used in Europe.

- Woad: The blue Celtic classic, at least in rumor. Although from a yellow-flowered plant in the mustard family (Isatis tinctoria), the leaves contain natural indigo, though in lower quantities than from the "true indigo" plant. When woad is mixed with weld, a distinctive green can be created that's called Lincoln green, owing to Lincolnshire's historic green textile production that also inspired descriptions of how local folk hero Robin Hood was dressed.

- Lichen dyes: Various lichens can be used to create a wide array of colors, and frankly any excuse to learn more about and work with lichens would be a delight.

I am also curious about various sources of browns and blacks, especially the latter, but these have puzzled me for a while because the most common go-to I hear about is black walnut. I'm allergic to walnut and would rather not engage with it, even wearing gloves. There are quite a few alternatives out there but I don't know which is regarded as the best walnut substitute.

Dyeing is not, however, a matter of simply immersing a textile in something that will impart color. Many if not most traditional pigments will run or bleed on their own if they get wet; they are not what people call "colorfast." An additional substance must also be used, called either a mordant[4] (which is a formulated chemical that sets color in place) or an assist (which may perform some of the same functions as a mordant but may also, or alternatively, affect the general appearance of the dye). Accordingly, I've been curious about working with materials like the below.

- Clubmoss: A number of clubmoss species, especially creeping jenny, are major natural sources of aluminum salts, which are a tried-and-true ancient mordant. I would also accept starting with refined mineral alum, but extracting aluminum from moss would be very interesting.

- Lye: Preferably made straight from wood ash. Because lye is so alkaline, it has a major pH effect on any dyes that it comes into contact with. This makes it a powerful assist since it will alter the item's final color.

- Oak tannins: Mentioned briefly in my post about leatherwork, these are a smelly but potent assist that may have been used to help darken certain colors, especially blues or blacks.

- Urine: This seems to have a wide array of historic uses in dyeing. It was used for fermenting and reducing particular dyes, also as a mordant for certain colors, and as an assist with controlling the desired shade. Like many people, I have contemporary concerns about using a potential disease vector like this, but I would love to know if there's a way to sterilize one's own urine without harming the properties that make it such a versatile dyer's substance.

Just to list these things feels a bit like creating a set of potential goals once I'm ready to let my hands get literally very dirty.[5] I'd like to experiment with far more than just the materials I've mentioned, but with this control over my scope I can do closer research and eventually buy, manufacture, or grow specific supplies instead of simply musing, "Hand-dyeing would be wonderful to try."

Having said this, however, it's not enough to acquire traditional materials easily, or to have a project in mind.

From aesthetics to ethics

Even though a dye may come from a "natural" source, that does not automatically suggest an older, more earth-loving extraction or disposal process. As with using any other resource, dyestuffs and mordants can be taken from our environment and from indigenous populations in destructive ways; the cochineal I mentioned earlier is a prime example, and an online friend of mine ritually grows their own saffron rather than participate in the highly questionable saffron supply chain. Meanwhile, the waste material from using various chemicals can also create serious pollution. This applies most on an industrial scale, but it's also been a problem pre-dating the Industrial Revolution, and I wouldn't want to reproduce it on a small scale in my home setting. If nothing else, I live on a septic system, so anything that goes down my drain also goes into the groundwater around here.

And I also don't wish to free myself a little further from the modern garment industry only to find myself actually engaged in just a performative vanity project. This is already of concern to me with how I source my yarn for knitting: until I can prepare wool myself from raw to spun form, I would rather buy yarn from artisans instead of factories, and even after I can make my own yarn I would rather be sure I can get the raw wool from sheep that I know were kept well. I don't want to go to the extreme of keeping the sheep myself — none of us can do everything ourselves, and to try would fall back into the individualist trap of misinterpreting "self-reliance" — but I do prefer a short, transparent, local supply chain.

This may mean that if I want to start dyeing as ethically as possible, I may be limited with certain materials, or I may need to dig hard for where I can find them, or I may need to rely on complex waste disposal techniques. Just to start getting practice, I might cut corners occasionally, but I wouldn't like to stay in that mode long-term.

For readers who may already have hand-dyeing experience, I welcome your advice. And while I continue to puzzle over the ethical challenges, I should remind myself not to put the cart before the horse: so far, I still need to progress backward from knitting to spinning. As the fictitious Juniper learned, whatever sort of witchcraft seems the most glamorous to me is likely not the activity I get to engage in right away.

[1] In fact the books belong to a trilogy, but I never got around to reading the last one.

[2] Marion Zimmer Bradley's Avalon series has always been a source of major literary and spiritual turmoil for me, but doubly so ever since the news broke about Bradley aiding her second husband in child sexual abuse and also sexually abusing her own daughter. Unforgivable stuff that makes certain events in The Mists of Avalon especially nose-wrinkling in retrospect.

[3] See: ancient Rome.

[4] The term mordant comes from French and Latin, referring to "biting." This comes from the idea of a chemical metaphorically biting into the textile in order to hold the color set there.

[5] I would wear gloves wherever possible, already being quite fussy, but I also know that if I want to get serious about this future practice I will probably need to resign myself to some colorful body parts on occasion.

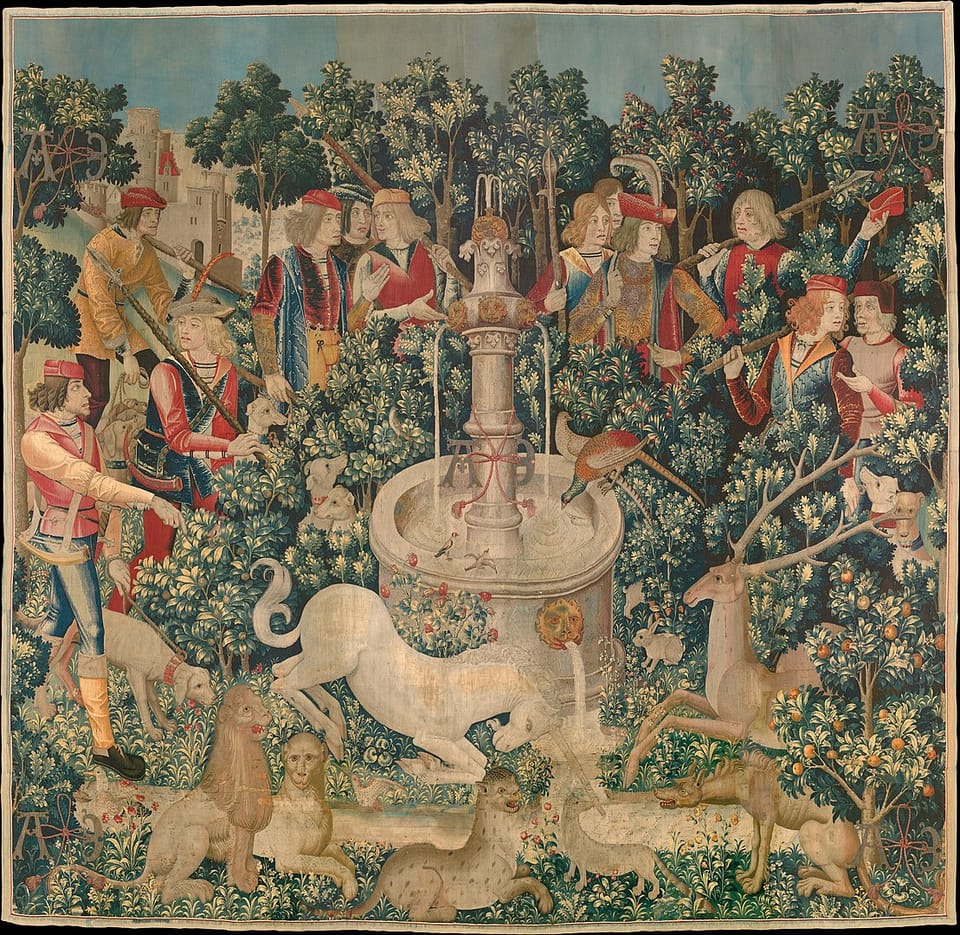

Thank you for reading. I hope this week brings you much beauty, and then next Friday I'll be coming back to beauty through a post on art: specifically artistic depictions of pagans and their kindred, and the eroticism thereof. After that, there will be a post for paid subscribers only, focused on the ways in which death work raises its head in kink through edgeplay.

Member discussion