First Quarter: Hail to the leatherworkers

It's Friday. Hello. I doubt I'm going out for any of the grotesque, cancerous feast of extractive commerce that's happening today — I almost never have, except when there's been a necessary errand to run — but I have some family obligations later and so I wrote most of this early.

For my periodic meditations on traditional hand crafts, I sometimes have thoughts about my own experience with making things myself, but I don't have and will never have enough time in my days to learn all of the crafts that intrigue me. Luckily, it's not my obligation to do so, and as part of recovering older ways I find myself often thinking about balancing the skills that every human benefits from cultivating vs. the skills that merit specialization. The latter kinds of skills cover many crafting disciplines and other arts that require countless hours of apprenticeship and practice; they are traditions that demonstrate the beauty of our social species' communality, connectivity, interrelatedness. I can see the importance of taking up woodworking without feeling like I must be the person to do it, as instead I can rejoice in people around me who are already studying.

So sometimes during these First Quarter weeks, there are crafts I can actually teach, but at other times I want to offer praise to those people whose skills are other than my own. Salt for the Eclipse does not include ritual, traditional knowledge that isn't mine to give out, but this project is also not just a window into a completely atomized hermit existence. As a node within a network, I have stories to tell of the other nodes, the best that I can, and at least one of my specialized roles is indeed of the storyteller.

My first ode to others' crafts is for leather. I can think of no better place, because it's a craft that does occur in my home, though not by my hands — and in leather there are bound many ethical questions whose answers are bones in the spine of my rites.

This post does contain graphic descriptions of animal part usage. While I find these usages very normal and in fact sacred, some are contrasted with things that I consider abominations, and either way I think it's best to warn the unprepared.

Leatherwork, through my eyes

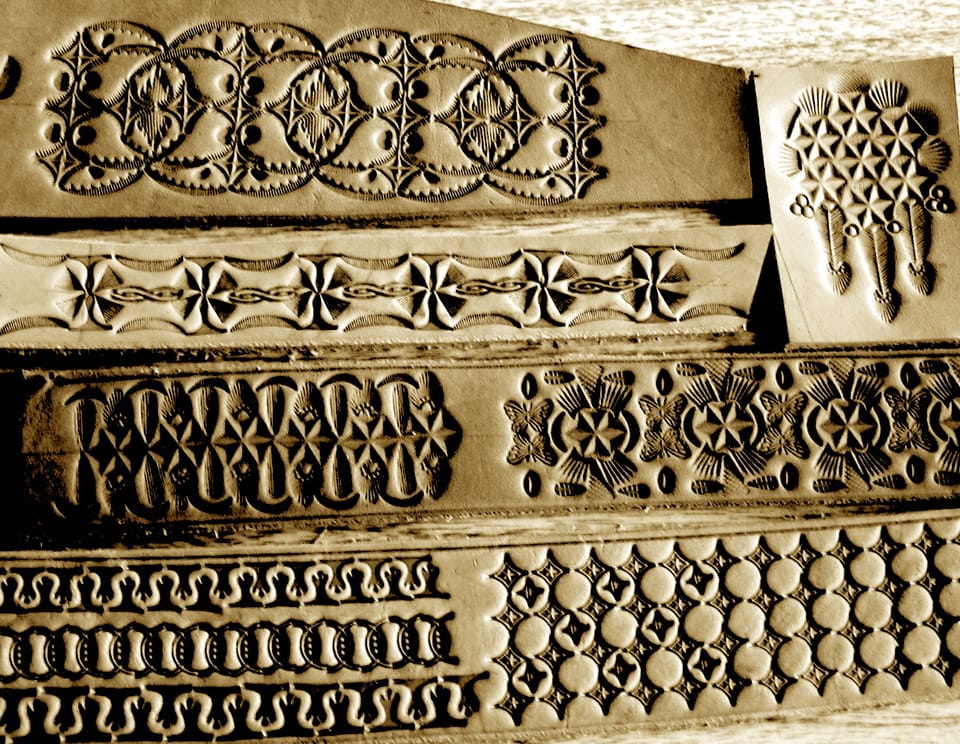

As an outsider, either rightly or wrongly I understand leatherwork as a parallel practice to fiber arts, only without fiber, turning from one-dimensional threads to two-dimensional sheets. Just like making things out of wool, for example, you can treat leatherwork as taking a prepared material and fashioning it into a decorated garment or utility-object — but you can also take a wider view of the whole process, considering not only leather cutting, sewing, and stamping but also dyeing, or even tanning, the actual creation of leather from hide. Maybe some people would consider tanners a separate trade, but I don't think they're any less connected to the crafting of leather than the people who wash, card, and spin wool are connected to the processes of knitting or weaving. You can learn the stages of a material craft as isolated practices, but you can also study them all together.

In any case, my owner does not do all forms of leatherwork, but the craft is one of his passions and callings. My primary exposure to it has been through him, and I'm honored to be the recipient of nearly every leather creation he's made so far.

Like many people, one of the first things about leather that I notice and love is the smell. It's easy to describe that smell as pungent, wild, animal, and other such adjectives, but of course it's also easy to forget that the smell is not from the creature whose skin has been transformed, and rather from the transformation: residual odors from tanning, along with the scents of preservative oils and more. So besides the smell, I love other things that derive more from the animal itself: the visual pleasure of staring at the grain of the hide, the tactile pleasure of tracing it directly, the special softness of the suede side infused by collagen where the skin met the flesh.

Depending on the type of garment or accessory, wearing leather makes me feel defended, protected, and loved, or a defender and protector in my own right. It also makes me feel closer with the animal in question.

And as a queer who kinks, I feel closest with my fellow riotous deviants when leather graces my body.

Leather & leather culture

Leather is not the only fetishized material in kink, but I would contend that when it comes to kink as we recognize it today (i.e. from the mid-2oth century onward), leather is the most significant one. Leather culture as its own entity is not synonymous with the kink scene, but under certain circumstances they are interchangeable — and leather is sewn into contemporary kink's foundations.

Some of this is well-tread lore for those reading, but in case it isn't: following the Second World War, motorcycle clubs sprang up in the United States and other countries, a pastime for largely ex-military men. Leaving aside the political complexities of that veteran involvement, these biker circles weren't all for queer men (to this day, I'd say most would position themselves as the opposite) but they still did serve as a natural queer meeting point. In little time, the protective leather apparel for riding bikes took on a homoerotic subtext among those in the know, propagated further by artists like Tom of Finland; as we queers are usually more open to our kinks in the first place, s/m and other fetish activities emerged in this subculture; and the bike clubs' high protocol activities, informed by those military backgrounds and a host of other factors, gradually metamorphosed into D/s power exchange prototypes.[1]

What began as an exclusively queer male subculture didn't stay that way for too long, either; queer women got involved earlier than they are often credited for. And in the end, while real queer, kinky bike clubs have persisted to this day, the biking became secondary to sheer leather eroticism — to the social experience of dressing in leather together, connecting through pain and sex in leather, often using leather-bound tools to inflict that pain, and more. In the decades since, straight people have increasingly taken advantage of this originally queer framework in order to discover that they, too, find vanilla sex either wretchedly dull or bizarrely more dangerous than sex involving hot wax; I hardly begrudge this discovery[2], but of course the more that kink becomes a mixed queer/straight scene, the less that it makes sense in my mind to call it leather.

I do belong to a modern queer leather club that splits the difference — it is made up of contemporary kinksters and has no earlier pedigree, but the interest in leather history and fashion remains. There is also no litmus test for who is "queer enough" to join, which is important, but certainly the overwhelming majority of members are queer without a doubt. And outside my own associations, I know that leather is still popular and well-recognized among many other kinksters, even if I suspect it's sometimes playing second fiddle to latex and PVC at this point. Latex suits my dominant side in ways that are hard to articulate, but in my primary submissive mode, leather is my kink garment. I have a leather chest harness and three collars: one for inside the house, one for outdoors or special gatherings at home, and another for holidays.

I hail and honor the makers of floggers and whips. I hail and honor the makers of leather-upholstered furniture. I hail and honor the makers of jackets, vests, trousers, chaps, hats, harnesses, masks, collars, leashes. I hail and honor the dyers and embroiderers. I hail and honor the bootblacks and repair experts whose own craft is still leatherwork as even without creating, they still maintain, fix, and heal the leather that is given to them.

Aging leather

Leatherworkers, your craft is old, much older than the (close to) eighty years of leather culture.

Even without motorbikes, for millennia and even back into unreckoned time you have been the servants of travelers. By the work of your hands our ancestors had tack for horses, and containers to carry supplies that were guarded against water — or in the case of some skins, containers to transport water through dry places. You have given us coats and other coverings to hold off rain from our flesh. You have given us boots and shoes to help our feet go further. Through my owner's mother's side, there is a centuries-old line of Cornish cobblers, so I think that leatherwork is held within this man's generational memory.

To those of you who have been tanners, I give thanks to the thanklessness of it. In some times and places the tanner was an outcast; their home and workshop would stay on the edge of town, for the whole place and the tanner too would smell foul from substances involved in the process. If you didn't wish to scrape hair off of hides manually, you would need to treat the hides with urine or lime; besides the aromas, in this there lay some risk from contact as urine, contrary to popular kink rumors, is not free of pathogens, and lime can cause alkaline burns and permanent damage to living flesh. As for the actual tanning of the hide now freed of hair, this would take vegetable tannins — the etymology is all the same — particularly from oak bark, and these can have their own stench. The best that I understand it, traditional oak tannin use presents minimal health risk[3], but a smell is a smell.

There has also been an apparently much better-smelling tanning technique that reaches back before the pre-modern production of the above ingredients. Even today it persists among indigenous communities. This is brain tanning. It sounds exactly like what it is, because brains as organs contain a perfect amount of fatty acid that can preserve skin just like oak tannin does, and in fact it produces a suppler result. When brain tanning, typically you use the brain of the animal whose hide has been collected. In one of our world's most stunning synchronicities, up to a certain size threshold[4] it takes exactly the amount of fat in the one animal's brain to tan its entire hide. I learned this very recently and have been thinking about it for days. The brain works very quickly when combined with stretching the skin over a smoky fire, and by using the smoke there are no decompositional odors — indeed, I gather the beautiful wood smoke scent is most of what remains.[5]

It does bear mention that even brain tanning is not without its tradeoffs. When dealing with animals who may carry prion diseases (transmissible spongiform encephalopathies), brains hold the largest amount of prions in infected cases. This matters when the disease is something like "mad cow disease," which is transmissible to humans as a variant of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, although mad cow disease is growing close to eradication. In a parallel example, cervine wasting disease is not yet proven to be transmissible from deer to humans, but as CWD is on the rise various indigenous peoples of Turtle Island, such as the Blackfeet Nation, have been starting to take precautions around the deer populations they work with for their own brain tanning traditions. In short, brain tanning is not going to make someone ill by default, but maintaining awareness around local prion disease outbreaks is crucial.

All told, any traditional tanning practice is rather sustainable, and the end product is a sustainability model as well. Well-tanned, well-maintained leather can last someone a lifetime. In permaculture, an animal killed for its meat would necessarily have its skin put to use, allowing the gift of their life to benefit an individual or community for more than just a few meals one week. This is in contrast to most mainstream leather substitutes, which rely on fossil fuels and other environmentally destructive factory processes. There are some plant-based faux-leathers gaining traction that are kinder, such as cork leather or mushroom leather, but it's very hard to find anything that can outlast leather-leather on all counts.

That is to say, I choose leather for a reason. Yet even in that choice, there is a genuine sustainability problem that must be acknowledged.

Empire & extraction

Leather as an ancient tradition is what works sustainably. It does not scale to the mass production level and still retain that sustainable quality. Many of my thoughts above have focused on traditional tanning because the cardinal sin of modern leather is chromium tanning. To the extent that I understand that process — and simply know that chromium is very damaging to living things — chromium tanning creates a mildly toxic final product and meanwhile its byproducts are the cause of local waterway disasters, most of all within oppressed communitites. You can still find plenty of leather made using oak tannin or other vegetable tannins, this being the origin of the phrase "veg-tan," but capitalist industry is allergic to prioritizing land and people over efficiency and profit, so given whatever reasons why chromium is seen as more cost-effective, chromium is the dominant tanning agent. Between that, a rather significant carbon footprint from raising kine[6] in large numbers, and similar issues, contemporary leather is not some magically ethical material in contrast to pseudo-ethical vegan products.

Sustainability crises are also not simply a problem of modern capital. The roots reach back deeper to the empire instinct, the extraction instinct. Leather items produced by slaves of the past would carry the same taint as leather apparel produced in a sweatshop today. In such spaces there is no craft, only misery. Under our most free, equitable, land-connected conditions, we could take leather from animals in the woods and fields around us, but most of us are not given that option. We take a shadow version.

So I do not praise the leather factories. I do not praise the leather companies. I do not praise the leather bosses. I praise the artisans, the workers doing the work, and in thinking of leather I have a constant reminder that we are past due to take back hand crafts from industry. I choose industrially processed leather because of durability, a craving for old ways, and the fact that any local alternatives are not currently available and I again do not have time to add one more skill into my repertoire; but this does not make me "better" than people who choose to only use leather substitutes. We are all dealing with vile, pollutant supply chains, and though I would contend that we can in fact do some ethical consumption within those constraints, it's only some. Mostly, here on the edge of the end of all things, I go by intuition more than calculation, and wait for the great extraction machine to burn out. In the meantime my owner still works leather, keeping a skill set alive for future generations who may need to know it more than we do.

Considering the kine

If something has seemed missing in my words all this while, I have not forgotten, only been waiting. This is the heaviest matter of leather. For yes, besides its beauty and history and value and the ethics around its raw production process, beneath every hide were once pulsing veins and arteries, and heaving lungs, and a beating heart, and shimmering nerves, and sentience.

In my adolescence, I came very close to adopting not only vegetarianism but veganism. It started as I refused to perform most assigned dissections in school, thinking of how unfair, unkind, and perverse it seemed to raise animals just for the purpose of being cut open. Then I grew insistent about buying no-animal-testing products, and uncomfortable about wearing fur and leather. Finally, I watched PETA videos about the meat industry and became viscerally horrified by factory farming and mass slaughterhouses. I don't want to give PETA too much credit because they're an opportunistic, sensationalist organization that harms animal welfare more than it helps, but by the time I saw those videos I was primed to respond not only to their excessive tactics but to a certain unfortunate truth behind them: there is something disastrously wrong with a world where millions of living beings spend their whole existence in prisons, tortured slowly, and then die in likely fear or agony, all to feed (or clothe, or educate) the creatures who ought to be the loving custodians of the land.

But my instincts never fully resolved that thought process in the direction of renouncing the use of all animals in my life. I had to contend with various problems, such as my personal dietary needs that virtually require periodic meat intake[7]; my growing awareness that plants and fungi very likely have a sentience of their own, and likewise that in crop production there are extractive abuses of both human workers and local animal populations; and the fact that at this point to abolish the keeping of livestock we would have to either release domesticated animals into environments that would kill (or be detrimentally impacted by) them, or render those animals extinct by various ethically debatable means. I couldn't physically become even a "mere" vegetarian if I wanted to, and I had questions about whether veganism was really the only way to go.

I should now say none of these issues are ironclad arguments against renouncing animal use. There is no "moral imperative" to use animals for anything. Contrary to generalizing, tokenizing statements about how indigenous peoples "all" hunt and rely on meat, there is variability in the ways that different communities have traditionally related to other living things, sometimes consuming all of them and sometimes not. The trouble for what I call ideological veganism — the belief that under absolutely any circumstance, animal use is wrong — is that variability in indigenous animal use demonstrates the true imperative, which is that we ought to be eating what our local land affords us, and what our bodies need. For some humans this makes a more herbivorous lifestyle both wise and ethical, but for other humans our land and bodies create omnivorous demands.

And since we are a custodial species, it is also our responsibility to listen to what our land needs for flourishing in its most complex and regenerative modes, which may at times require that some entropy-forming animals have their population reduced, just as it may also require burning some brush. I have gradually come to believe that the problem with using animals is not the actual use but the lack of reverence and sacredness in the process. Animals kept mainly for milk or eggs should be treated as beloved companions in symbiosis, and live out their natural lifespans rather than die as soon as they're past their prime. And it isn't enough to say a prayer on the abattoir floor; killing animals, whether through hunting or fishing or ending their lives after a long span of domestic service, should be a fully animist process, drenched in gratitude for the life being passed to us for our sustenance. It certainly shouldn't happen for every meal, and there should be ceremony when it does. In turn, upon death all parts should be put to use — all meat cuts and all organs, and with the rest becoming leather, fur, sinew, bone, and more.

This is another thing that does not scale to the industrial level, and cannot. Kine, the main source of leather today, cannot be raised as they currently are, accelerating the climate collapse. They are in fact a wildly costly animal to raise even on a localized level, and they exact an ecological toll surpassing sheep, who are themselves not without sustainability challenges. But even if we dealt with other species as a source of food, dairy, clothing, etc., we would still create a cruel, desacralized situation by mass-slaughtering deer, seals, or what have you. The rites are everything.

Over time I've settled on eating animal products sourced from the most free-range, cageless places that my budget could allow for; for carbon's sake, eating as little red meat as my body could endure; eating less food of all types that I know comes from hyper-exploitative supply chains; and eating less meat in general. In turn, I am working on resolving my complex, warring impulses about leather — and fur by extension. On the one hand, right now it's very hard for me to find these things from nearby places where the animals are both treated well and also will actually be eaten, and my owner and I are not in a position to hunt or raise these creatures ourselves. On the other hand, as I wrote further up, leatherwork is a skill set worth preserving, and animal hides and pelts are durable sources of warmth and protection that will matter in the time-to-come. When the industrial capitalist machine finally breaks for good, which may happen in this lifetime, people in many places will fast lose the luxury of finding plastic leather substitutes that wear out quickly. I think it's worth investing in more reliable options right now, even if it can leave me with a queasy feeling.

Is this the only right way, or the least wrong way? I doubt it. But it is my way. I am certainly accumulating a ritual debt to kine, and to certain other animals, and as I write this, I know that I am past due to build proper rites of praise to the animals who give us leather, just as I have wanted to sing my praise to the human-animals who work that leather into magic.

Leatherworkers, I thank you. Leathergivers, I thank you.

[1] This is definitely messy, murky territory insofar as leather organizations claiming a pedigree back to the "Old Guard" era often do not feature the consent politics that contemporary kinksters expect. This is one of the main reasons why leather and kink overlap but are not perfectly identical. Nevertheless, while I often mistrust self-described Old Guard institutions and avoid using the term in my own kink affiliations, I have respect for the contributions of leatherfolk, especially original queer leatherfolk, from what's considered the Old Guard era.

[2] Quite the contrary, since vanilla sex in the sense of hegemonically normative, unnegotiated copulation is an experience I have no intention of ever having again.

[3] Of course some people are sensitive to tannins, and when consumed or absorbed in excessive amounts the essentially medicinal properties of tannins turn, like all things, to poison. While I'm no statistician, I wouldn't say this makes traditional oak tanning any riskier than dealing with the smoke of a blacksmith's forge or the metal and wood dust of other crafts. Newer methods of tanning are far more toxic, however, which I address above.

[4] I believe in the case of very large bovines like bison, or bigger.

[5] If you are interested in more information about brain tanning, here is one of the guides I've consulted in learning about the practice. Be warned there are graphic images. For a more general introduction to traditional tanning methods with easier viewing, this is a good start.

[6] Kine is the true plural of cow in the sense of all genders of cow, unlike cattle as the plural for females.

[7] As I cannot eat peanuts or most tree nuts, my plant-based protein sources are largely restricted to other legumes. As I viscerally dislike the taste of most soy products besides soy sauce and experience inflammation from too much soy intake already, that narrows my plant proteins further to things like beans and lentils. But while those could maybe suffice, my heavy menses now leave me chronically iron-deficient, which can be partially addressed through iron-rich vegetables and ferrous sulfate tablets — but in the end, I will always veer into anemia if I don't acquire true heme iron. I usually rely on eggs, fish, poultry, and pork for this, but about once a week I allow myself some beef or lamb.

I hope this was not a difficult read for anyone, but I am open to dialogue if it was. Thank you for reading in any case. Next week I will have a much less fraught post concerning writing as a devotional art, although the week afterward I will be venturing right back into challenging territory on the topic of violence — any and all violence. Until then, be well.

Member discussion