New Moon: The Devil as Pan

It's Friday, and not only is the Moon new, but the Earth is at aphelion, its furthest annual distance from the Sun. I don't consider the latter situation to be of particular ritual significance, however perhaps I should, since as hot as summers have become at my latitude they are still less hot than they could be if the Earth were at perihelion or somewhere in between. Maybe I should give thanks for this reprieve in my hemisphere. In any event: hello.

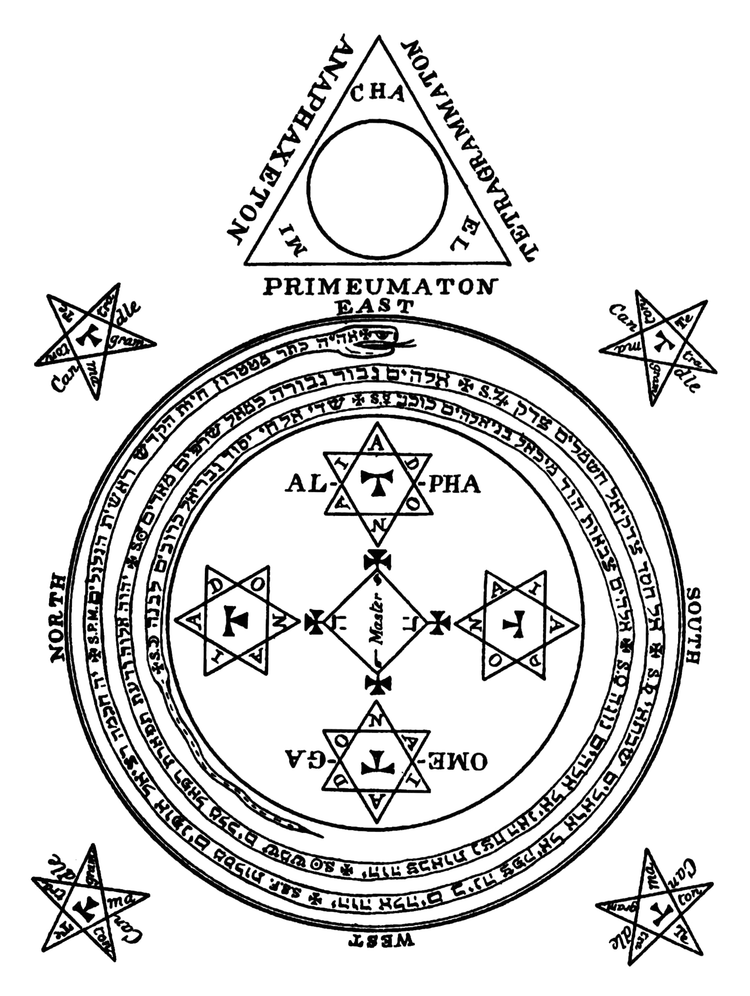

My reflections today directly concern the Devil after a few months away from that topic (especially for public posts). More than a year ago, I began a journey of immersion in animist thinking, which is only one of the modes by which I approach my witchcraft; during worship, this animist focus made me turn most often to the aspects of my god that are expressed in certain pre-Christian cosmologies. However, since Calan Mai I've now been trying — creakily so far — to immerse myself for another year on the other side of my rites, those based in the occultism and ceremonial magic of the "Western" (in this instance more like pan-Mediterranean) esoteric tradition. In that context, even though esotericism is a syncretic archive of pre-Christian knowledge, it's always flourished and been transmitted through currents deep in the shadowy places of centralized, urbanized empires, forming a countercultural underbelly that also couldn't exist if there weren't something to oppose; the rites are powerful but a few steps removed from living with the land, and over the past couple of centuries a Christian-molded figure has emerged as Christianity's potential undoing. Here, I most plainly recognize my god as the Devil, the dark seed that is generated by the status quo but eventually builds the power to destroy it.

To better motivate myself toward all the occult research I've sworn to do but have so far put off, I meditate now on Satan as an occult deity. Ironically, though, to do this I must start by examining yet another pre-Christian god: Pan. Much of what I'm about to say mirrors a few writings and lectures by Ronald Hutton (who else), so don't mistake it for my original research; it's simply vital pre-existing analysis. The main difference is that while Hutton's work on Pan chiefly addresses Pan as the origins of the modern neopagan "Horned God," I'm just as interested in a secondary outcome of that formula.

Deconstructing "paganism"

In the Greco-Roman[1] imperial sphere that would eventually beget Christian culture, pagan was not a religious designation so much as a statement about the urban/rural divide, for the pāgānī were the people of the countryside — whether in those lands that Rome had conquered already or in those lands Rome had merely set its sights on. Then as now, the city folk looked down on the country folk; and even in the rural spaces where privileged classes existed like the noble villas or the legionary outposts, a distinction was still drawn between the "cultured" top of the pyramid vs. the equivalent of hillbillies. In Roman or earlier Greek cases alike, the most elevated gods were linked with the human "civilized" world as much as with "wild nature"; and perhaps even moreso with civilization where Rome was concerned. Figures like Jupiter and Saturn governed the thunder and the crops, but functioned more as patriarchs; Juno was the Queen of Heaven, but emphasis on the queen; Mars and Minerva oversaw war, and in Minerva's case also various hand crafts and scholarship; Vesta tended the human hearth; a figure like Bacchus was significant, but inherently an outsider.

As Hutton has explained in The Triumph of the Moon and elsewhere, after Europe became Christianized it was still quite acceptable for someone to refer to the gods of Rome (and Greece, but again especially Rome) in both a literary and quasi-reverential way. A quick look at Shakespeare shows this persisting in anglophone culture all the way into the Elizabethan period, and then there are countless other examples from the immediately surrounding centuries. On the one hand, urban-central-imperial Christianity rejected the "paganism" of the same rural peoples that Rome had colonized and sneered at, such as the Celtic and Germanic tribes; this left those gods to be interwoven with folk Christianity and halfway preserved in that setting, but not with any of their original mythology intact except for whatever managed to be reinterpreted in Christian-era writing. On the other hand, though, borderline idolatry was permissible and commonplace if you simply invoked Jove or one of his Roman kindred.

Essentially, what we would now classify as "pagan sensibilities" existed outside of a folk context throughout the medieval and Renaissance periods, but people at the time wouldn't have described those sensibilities as pagan unless the speaker were among the most zealously Christian; and the folk context of paganism was itself disparaged, as the lowercase-g but still elevated gods were regarded as "civilizing" influences that lifted humans up from corrupt, fallen nature.

Nonetheless, as Protestantism further stripped animism from that continent, as enclosure acts stole the commons, and then as the scientific and industrial "revolutions" took place, a seismic shift occurred. European societies became either more secular on the whole, or at least more opposed to what they called superstition, and exponentially fewer people began to live in harmony with the land, earning their wages from factories, metastasizing mining, deforestation, and more. For these people's ancestors, there had been no need to revere "nature" because nature had simply been what the rest of the world looked like to most humans — or for a privileged few it seemed transparently "inferior" to live in an indigenous way rather than an extractive, imperial way. But suddenly, an impulse arose to revere nature as an abstract yet tangibly (painfully) missing entity; this was Romanticism, the first backlash to techno-economic modernism.

Out of the Romantic movement stepped Pan.

From satyr to Satan

As implied above, Pan was not a major god of Mediterranean antiquity. Originally most of his worship took place in Arkadia, a mountainous region on Greece's Peloponnesian peninsula; he was a god of the woods and fields, but almost just a demigod, sacred primarily to shepherds. Spring and fertility were somewhat his purview, and he guarded flocks, but he was associated with lustful, ignoble, nymph-harassing satyrs, arguably a satyr himself. He was no Olympian. The Romans appropriated and copied him in their own mythic realm, but again as a lesser figure. The main change they could have made was giving him a more goatlike appearance, in keeping with how their goatlike fauns eventually supplanted what the Greek satyr referred to — the original satyrs in fact having horse ears and tails.

Despite Pan's relative unimportance both during and immediately after this time, the memory of him was not completely forgotten. And it was to this memory that Romantics of the early 19th century would turn in their instinctive quest for a god of the natural realm that they sought to rekindle relations with. Writers such as Shelley and Byron discussed Pan as though he were a deity they earnestly worshiped; these particular men did not necessarily revive his cult[2], nor were they the first or only examples of Pan-adulators in that cultural milieu, but they can be considered prominent ones because of their own enduring fame and because of the conceptual overlap that Pan would hold with their shared Paradise Lost obsession and Shelley's equal fixation on the Prometheus myth.

Right there, right in that nexus, one can sense potently mingled environmentalist, anti-authoritarian themes: in recovering our ties to the land, we must also throw off the shackles of Christian hegemony and all other hegemonies. Of course, not every Romantic was as far to the left as Shelley, so some of the movement was twisted into nationalism and grotesque race fantasies. Regardless, though, the early Romantic regard for Pan set off a fad that would last more than a century and inject itself into numerous artistic and/or occult subcommunities. Inevitably this Pan also became a metaphor for sexual liberation in the face of social repression, so most of the 19th-20th century artistic output that can be found about Pan has an implicit sensuality if not what I can only describe as barely-restrained horniness (e.g. Arthur Machen's short story "The Great God Pan").

Prior to industrialization, the Devil had been envisioned or depicted chiefly as a reptilian creature (the serpent, the dragon) or as a humanoid demon; but Pan's presence among modern heretics may well have been what turned Christianity to finally make the Devil a horned, faunish entity. And as Hutton focuses on, the imagery and archetypal conceit of the "Horned God" that arose by the early 20th century also depended on more or less retrofitting the newly important Pan for other potential nature/fertility gods like Cernunnos. Meanwhile, though, the likes of Aleister Crowley and his direct or secondhand acolytes would spend all the remaining decades till the present day teasing out the satanic associations of 19th-century Pan reverence, giving us a visual and political language for Devil worship under late capitalism.

I am not fond of Crowley, charlatan and bigot and megalomaniac that he was. However, I know it's by my exposure to satanic occultism in the mold he was working from — the mold of Pan — that enabled me to develop the satanic practices I maintain today. My hope is that I can pursue the Devil-as-Pan to countermodern ends, but not to reactionary ones.

An Adversary for this age

As I've probably said here before, I do not think it's right to conflate Satan as he appears in a Christian context with "Satan" as perceived in parallel for other Abrahamic religions. Some of my caution is (I hope) basic cultural sensitivity, but the biggest factor is truly what I've described in this post. The Devil who's the enemy of Christianity has gone through permutations that take him rather far from any shared source material.

In Judaism, as I understand it ha-satan is not one cohesive figure, nor even always a personified agent; the phrase may be identified with Samael, who is the angel of death but in some later texts is also representative of Christian hegemony's existential threat to the Jews; ha-satan may also be Azazel, the recipient of the "scapegoat" sacrifice on Yom Kippur in contrast to the goat for Yahweh, as Azazel and Samael themselves are sometimes combined; and meanwhile there is the yetzer hara, which is an inner temptation to do evil but not an entity who offers that temptation. Meanwhile in Islam, al-Shaytan is best known as Iblis and there are varying perspectives on his relationship to jinn, including whether he is a jinni himself or rather an angel who sired the jinn; he is a tempter who rebelled against authority, but he is also wrapped up directly in pre-Islamic animism of a very different landscape than what Christianity syncretized with. For these religious-cultural contexts, I would not presume to argue that the "Satan" there is a positive force.

As for the context I've lived under, though, of course I have embraced Satan the rebel, Satan the adversary, Satan who would rather reign in an uninhibited hell than serve in an authoritarian heaven. And I see him in Pan, and I try to heed Pan's call to the meadows, to the woods, to the green places forgotten and attacked by central imperial development. He is one way in which Satan plainly works as the power against empire.

If I wish to bridge my ritual modes between the animist and the esoteric, then studying the modern lore of Pan further might well be the way to begin.

[1] I use this phrase dryly, as the Greek-speaking spheres of antiquity had their own empires but I think Greco-Roman can sometimes imply an organic, nonviolent cultural continuity between those empires and Rome's. Rome "Greekified" (that is, Hellenized) itself through several centuries of colonially occupying and appropriating from Greek peoples.

[2] Especially not the mercurially insincere Byron. But Shelley did seem to take Pan very seriously indeed.

I will reiterate that a good deal of what I've said in this post could not have been written without previously reading or listening to Ronald Hutton's insights. However, putting this material into my own words has helped me to further internalize the knowledge, and I hope it was interesting to you. Next week's post concerns my first psychedelic experience but will be for paid subscribers only; the week afterward I'll have a public post of praise for those whose hands work with wood.

Member discussion