New Moon: Free will

It's Friday. Hello.

I was going to write this post a certain way, and now I'm not sure what will happen. For the past 48 hours, especially yesterday, I've had a flareup of the medical mystery problems that I've been trying to investigate and treat since September; yesterday I also conveniently and at long last was able to consult with a couple specialists, one of whom I had been hoping to see this entire time. It's an exhausting tale that I still don't want to recount here in full unless I both have answers and know some way of using my situation as an object lesson for some broader topic in this newsletter. I write personally enough here that I'm not worried about the saga seeming "off topic"; however, I prefer not to simply offload strong emotions here unless I've at least reached a stage of processing those emotions where I can contextualize them, find the narrative in my situation, make the meaning.

But in any case, now there is a clearer diagnostic roadmap ahead than the bureaucratic quagmire I was trapped in by insurance and incompetent facility staff — and simultaneously I am very tired, from brain to bones, so though writing is a healer for me I do not know how sharp my thinking will be around philosophy. And I had planned to write about free will, and normally a discussion of that phrase is philosophical in nature, and I regrettably have a philosophy degree.

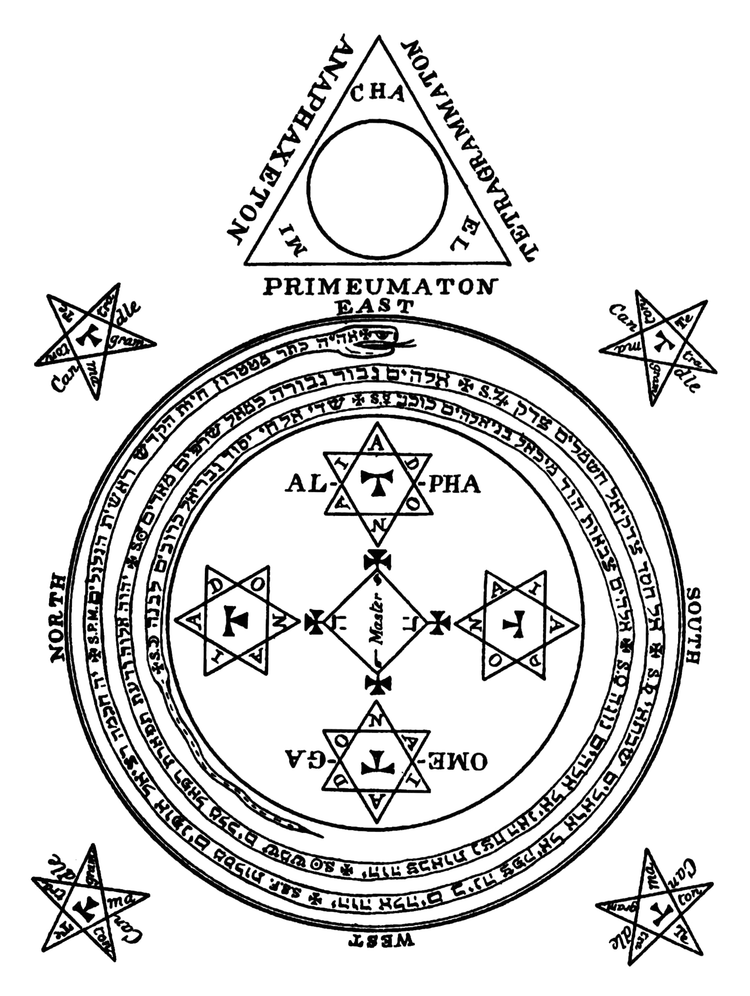

What I feel capable of and interested in writing today is not as analytical, cohesive, or lengthy as I originally envisioned. Yet I will still try to offer some thoughts on free will — the mystery of it — because something I periodically find in ritualist discourse is a tendency to focus on seemingly opposite concepts from free will, such as fate, luck, or synchronicity, and I've wanted to complicate that situation. I feel that navigating existence is often about accepting the hand that has been dealt to us, but just as often about accepting the circumstances in which we are the hands that do the dealing.

Here are some things I've been considering in that vein. I've strung the thoughts together as best I can, but I make no promises.

Determinism

We can observe so many things in the world that suggest free will is absent, that all is determined. One by one, the list of reasons mount for why our lives are beyond our control, and why the control we perceive is an illusion.

First, there are the now-routine cognitive science research papers that indicate our consciousness is an overlay above a deeper decision-making system that we do not consciously feel. When someone chooses to do something like stomp on the floor, neurons in their brain activate to indicate that choice, but this happens a short but statistically significant amount of time before the person reports making that choice. Their conscious experience of decision-making is evidently separate from the decision-making itself. The real decisions are happening in what seems like an impenetrably subconscious box, and it's impossible to scientifically observe what makes this decision-making process in a human any different from the decision trees followed by computer programs. And if we can't know what actually governs someone's decisions, then seemingly we can't know whether they're freely choosing anything vs. behaving in a way that they were inevitably going to behave.

Then there are inherited behavioral factors. Whether caused by genetics, epigenetics, or sheer upbringing — "nature vs. nurture" doesn't matter here — our parents or parent-like figures have a profound impact on our personalities from birth onward. We inherit behaviors that were either encoded in our very bodies or modeled regularly for us to mimic. Naturally we may tell ourselves that we aren't going to "turn into" our parents as we age, working hard to improve aspects of our behavior that we consider negative traits passed down from ancestors, but this very struggle is still impressed on us by our unique parental circumstances. Also, most people do not shake off their inherited behavioral patterns completely, and thus generational trauma (or advantages) can transmitted for centuries. And even the very absence of a parent is its own influence. Taking all of this into account, it seems absurd to suggest that we could do absolutely anything we wish with our lives; at the very least, our behavioral options are restricted and shaped in ways that severely increase the likelihood that a given person will go through life doing certain predictable things.

Next, among the ritually inclined there's the matter of divination, prophecy, precognitive clairvoyance. For my own part, I do not use divination to predict a definitive future, only to intuit possible futures, but many people regard these practices as ironclad looking-ahead to what not only may but shall occur. And even for those of us who are more flexible, merely expecting an array of possibilities still suggests that those possibilities are better guaranteed than others. For a very broad example, it makes sense to declare the Sun will rise tomorrow morning not only because it's risen every previous morning, but because all basic signs and our very guts point to the cosmic conditions tomorrow still being correct for the Sun to rise. Most acts of divination are not dealing with something so obvious, of course, but when practicing divination seriously there must still be a comparable certainty attached to what we sense is ahead, even if details are a bit vague.

And indeed, there is no value going through life assuming that at any given moment the most chaotic randomization of possible events will happen. We assume cause and effect relationships because it would be laughably inconvenient not to, and also because causality is the simplest (and per Occam's razor therefore more truthful) explanation for why events proceed in sequence. So even a total "rationalist" who abhors divination still feels free to issue if/then statements about what's going on in the world. Taking all this into account — noticing how causation affects both living and non-living things — we might then well assume that in a parallel universe from our own, if all factors preceding a given situation were precisely the same as they are here, then the outcome to the situation in the parallel universe would be identical to this one. From there, we might just as well entertain the idea that somebody who believes they've made a free choice has not really done so: they have only done the exact thing that all causative factors in this universe have led to them doing.

There are still other reasons why someone might be a pure determinist. For Calvinists, belief in predestination was a potent mechanic for inducing sociopathic behaviors in certain people and trauma responses in others; the righteously self-centered would say to themselves, "I can do anything I like and it doesn't matter because I bet I'm being sent to heaven anyway," while the systematically abused would say to themselves, "I'll do my best because it's bad enough that I'm already being sent to hell, maybe somehow I can get myself out of this." Determinism can also help many people solve "the problem of evil": terrible things can happen in the world even in the face of a benevolent, omniscient, omnipotent god's existence, because these terrible things are all part of the god's plan and thus inherently not quite so terrible as they appear.

Whether these last few considerations apply to you or not — obviously they do not apply for me — I've raised an array of reasons for a deterministic worldview since determinism is not an exclusive hallmark of the theist or the atheist, the animist or the scientist, the witch or the witch-hunter, the Christian or the non-Christian. It also isn't an exclusive hallmark of the political left or right. It is pervasive, even if I'm most interested in determinism's implications for people in my left-ish ritual realm.

So if it is pervasive, and if I've described some extremely tempting logic, why is belief in free will important?

Existentialism 101

People who care greatly for notions like autonomy and consent often react with hostility toward determinism; for if all events in our lifetimes are unavoidable, including the choices we think we're making, then someone may reach a further, awful conclusion that when a person consents to something, it's not a meaningful action, and therefore no real violation occurs if their consent is ignored. We also don't wish to create rhetorical opportunities for someone to say that because people have destinies at all, perhaps certain sorts of people (like those who have external gonads) are destined to dominate other sorts of people (like those who have internal gonads). Even if determinism isn't absolutely a right-wing ideology[1], many expressions of determinism can rapidly evoke and inculcate fascist mindsets.

But supposing a determinist hasn't skidded down that slippery slope, there is a larger, more basic problem: determinism eliminates any need to behave ethically in the first place. Deterministic thinking underpins what people describe as the "fundamental attribution error": when I do this thing, I had good reasons, whereas when someone else does the same thing, they don't. You do not need to be a Calvinist to think like this, although Calvinism (and Protestantism more generally) did a magnificent job infecting Euro-colonial culture with an especially miasmic flavor of such logic. Nowadays people of all political persuasions are at risk of thinking this way; I see it in my own circles all the time. I have no doubt that I make the same mistake myself even though I desperately try not to. The fundamental attribution error actively enables the exploitation of other people, or the dismissal of their suffering, because we have shrugged off any sense of responsibility. If there's any free will to be found, it's in the actions of anybody but ourselves. They did the thing that meant I had to respond in a violent, abusive manner.

I discovered Jean-Paul Sartre's style of existentialism more than 15 years ago, and although it is no longer the blueprint for the anti-religious anarchism I would then adhere to for a little while, I still owe a good portion of my ethical compass to Sartre's overt philosophical treatise Being and Nothingness as well as the ideas communicated through his theatre and fiction. The heavily digested summary of his existentialism is that belief in fate is a "get out of jail free" card for behaving ethically, and that l'existence précède l'essence (existence precedes essence), meaning we are undetermined, completely free entities before we ever adopt determined, essential characteristics. Our inherent freedom is terrifying insofar as being truly responsible for ourselves is a psychological burden that few people can easily accept, hence why so many lean consciously or unconsciously toward deterministic logic instead; but we are free nonetheless.

Understanding free will in this manner does not have to contradict the numerous factors that affect why our range of likely life choices will not be infinite. Having the option to freely choose our actions does not mean that we will make all our choices in a vacuum. What matters from an ethical standpoint is that within whatever restrictions are imposed around us, we should consider ourselves free to choose the behaviors that are as close as possible to what we perceive as right, and not the behaviors that we perceive as wrong. Even if our brains are not empirically distinguishable from computer programs, if we feel free then we should act as if we are. Better to mistakenly make many good choices that don't really matter than to mistakenly make many bad choices that do matter.

But if that is the simplest way I can describe my own belief in the necessity of free will, I also think you can find the argument in just about any rudimentary philosophical or religious discursive space. I have mulled it over plenty in these 15 years, and although the classic "free will vs. determinism" debate is nominally solved by my position, the real mystery of free will is now found in turning the tables back — in considering why belief in free will has its own historically problematic effects.

Free will imposed vs. free will in flow

Free will in its logical extreme is individualism. For most people in a Euro-colonial mindset, it can be hard to understand why individualism is not a positive word. And personally I will not argue that its polar opposite in collectivism is especially positive, either. Nevertheless, individualism is itself another ideological byproduct of the Protestant-capitalist value system that has become a curse on the very earth.

The individualist is not content to have free will, but believes they must impose that will. The individualist also rejects ethical accountability; instead of deterministically claiming they were inevitably driven to do something horrid, they excuse their actions on the basis that they were acting freely and that to act freely is inherently good. Any restriction on their behavior is an injustice, even if the restriction is simply a request for them not to murder or rape people — or an expectation that if they take something from a forest or field, they should not take too much in case that ruins others' ability to collect things from those environments in the future. The individualist demands survival of the fittest over mutualism. The individualist severs relations because relations hold them back. The individualist disrupts critical natural systems out of a childish lack of awareness that they need to leave those systems in place for their own survival.

Many lessons I have learned as a ritualist — as a witch, animist, occultist, any other label one might use — are about moving freely, but still moving with the current of life. Recognizing the past and the future as active realities within the present moment. Our free actions still have consequences, as did our ancestors' actions.

The mystery of free will, then, is that all things have free will, and those wills forever must clash and influence each other like the interlocking of tectonic plates. We must understand free will in a context of things beyond ourselves. We must be conscientious agents among other agents, respecting them, learning harmonious behavior among them.

Not for the first time, today — fitting perhaps in the context of my health ailments — I think once again of the "serenity prayer," not as a Christian but as a satanist. My latest iteration is:

Grant me the serenity to recognize that which is beyond my will, courage to exert my will where I can, and wisdom to learn the difference.

And now I go to rest my mind.

[1] And let us not forget the overwhelming preponderance of Christians on the far right who would claim they entirely support free will, since that was their god's gift to Adam and Even despite Satan's urging for the opposite.

Thank you for reading. Next week: a hand crafts post on traditional dyeing techniques. The week after: paganism in art, and the erotic undertones therein.

Member discussion