New Moon: Danse macabre

"I see them! Over there against the stormy sky. They are all there. The smith and Lisa, the knight, Raval, Jöns, and Skat. And the strict master Death bids them dance. He wants them to hold hands and to tread the dance in a long line. At the head goes the strict master with the scythe and hourglass. But the Fool brings up the rear with his lute. They move away from the dawn in a solemn dance away towards the dark lands while the rain cleanses their cheeks of the salt from their bitter tears." — Det sjunde inseglet (The Seventh Seal), dir. Ingmar Bergman, 1957

It's Friday. Hello.

This has been a difficult week for me. A particularly bad psychological struggle with my day job; I need to quit, but not before I have a couple proverbial ducks in a row, none of which are lining up fast enough to be helpful, so until then I'm trapped. And among those misaligned ducks I've now faced a hopefully temporary but currently hard-to-ignore logistical and physiological hiccup in my fertility quest; it may well resolve in just a month, but until then I have my mind's catastrophizing engine picturing all the worst case scenarios.

Variations on longstanding themes, but worse than usual. In the most acute spells, five or ten minutes at a time, I feel not only anxiety, not only fear, but abject despair. Which is not a stranger to me, but it's rare enough that when I feel it I know just how deep a river I'm fording.

I could stand to seek some ecstatic release, somewhere. And I do not mean in the sense of creature comforts or the most basic, private act of self-love. I mean a fiercer, wilder way of embracing despair in order to move beyond it. While I'd already planned for a while to write about the danse macabre this week, the subject strikes me close today.

Apocalypse past

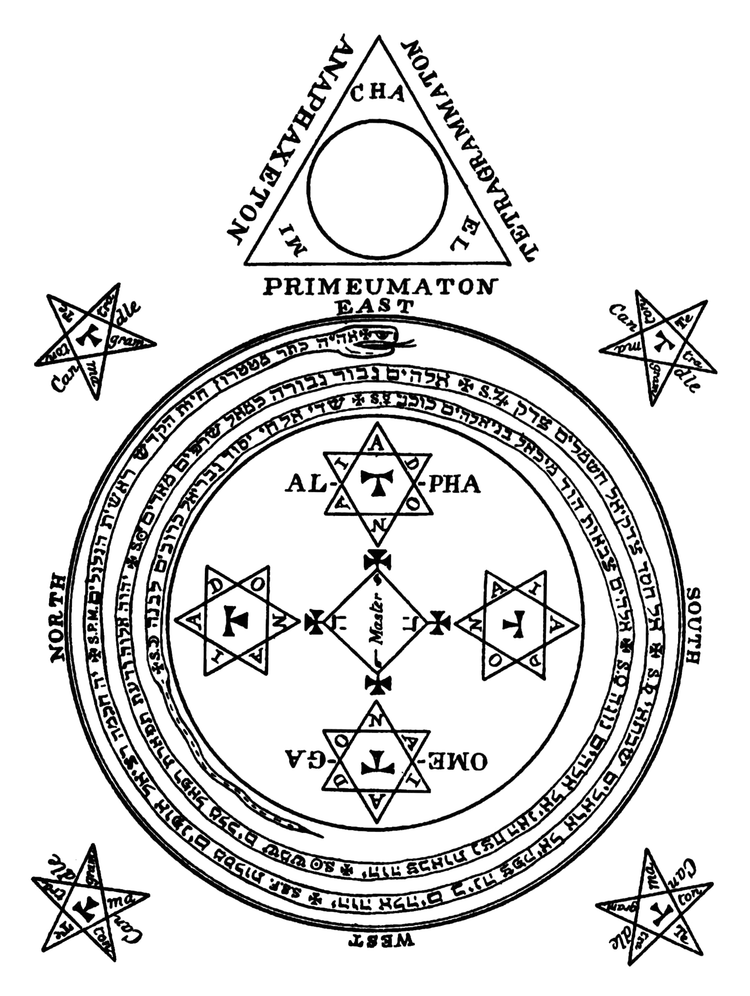

The danse macabre is a motif in artwork of the late 14th century CE onward, concentrated particularly before the late 15th century but also persisting in later material through referential inspiration. In the danse macabre, one or more skeletal figures lead a dance populated by living humans from all social strata, or occasionally (as in the case of the 1493 woodcut that graces this newsletter's landing page) the only dancers are skeletal but they still wear clothes suggesting various stations from when they were living. The images are generally known or assumed to convey anthropomorphic Death as a great leveler, just as the Grim Reaper carries a scythe that cuts down all in its path. No matter how wealthy or powerful some of the dancers may seem, they must all meet the same fate as the more humble folk beside them.

Scholarship tends to agree that there were very clear sociological conditions that informed the development and popularity of depicting a danse macabre. The motif arose nakedly from what historians call the crisis of the late Middle Ages, which was the severe upheaval wrought by factors like war (especially the Hundred Years' War), famine, and the Black Death. I don't think I'm alone in speculating that the latter feels most significant to why an artist might choose to depict Death the leveler: war and famine are not quite so egalitarian in their victims as disease can be, certainly in that era. That is to say, the more socioeconomic privilege somebody has, the less likely they are to live in conditions where they'll be exposed to disease in the first place — but once they actually catch the disease, that affliction can only resolve within their very flesh. Even war and famine, though very challenging to survive, depend on external factors that might reverse themselves. Once an infection takes hold, the body will either fend it off, or it won't, and even with the assistance of modern medicine we remain at the mercy of whether our immune systems function effectively.

Perhaps all of this is speculating a little further than necessary, but if nothing else I know that when medieval diarists who survived (or died in) the Black Death wrote of their cities' or villages' people being felled like trees, the language is particularly apocalyptic. As I've discussed in other posts, I'm convinced there may be almost no event with a more significant traumatic effect to the European psyche than the unprecedented scope of that pandemic.[1] The social impact of covid and even the 1918 influenza pandemic pale utterly in comparison, which is remarkable considering how real their impacts are and were.

Having thought of the medieval apocalypse a good deal lately, I also decided to rewatch Ingmar Bergman's The Seventh Seal last month. For those unfamiliar with this existentialist classic from mid-20th century Swedish cinema, the most visually iconic plotline is that of a chess game between a returning crusader knight (played by Max von Sydow) and the hooded figure of Death itself; but more broadly the film depicts a series of incidents as a few travelers pass through a landscape where the people have been devastated by bubonic plague. The chess plot engages with questions of whether to believe in a benevolent god and afterlife; overall, though, I interpret the film's trajectory as an attempt to portray how different people respond to cataclysmic situations, using Europe's greatest cataclysm as a potent setting.

On this recent viewing, two scenes stood out to me even more than they usually do. One is a procession of ritual penance as Christian flagellants trudge in physical and emotional agony through a village center; their leader makes a chilling speech about how there is no hiding from the plague, from dying, and the scene is bookended by the flagellants singing the "Dies Irae," which as its own motif in music has been recycled and referenced at least a thousand times but originates in Gregorian chant and lyrically concerns the Day of Wrath (Judgment) in the Book of Revelation. It's entirely possible that real medieval flagellants might have been moved to sing the "Dies Irae" or a similar option as they flogged themselves through the streets; and Bergman's direction turns this scene into a profoundly hair-raising spectacle.

The other scene is the final moment of the film. Skip this paragraph and the one afterward if you don't like to know how a story ends before you've begun it, but essentially a large contingent of the traveling characters are trapped by Death and then witnessed at a distance, dancing together in silhouette. Given their various social stations and Death taking the lead, it's a cinematic danse macabre described by the witness Jof in the quote I gave at this post's outset. Presumably, all these dancing characters are now dead or about to be led to that fate.

In the "Dies Irae" scene, I think it's hard to see anything positive on display; the horror is less of death and more of humans fanatically reacting to it, but it's horror nonetheless. By contrast, however, the danse macabre scene feels as if it can be interpreted numerous ways. Perhaps these people are proceeding joyously to their own demise, the tears washed from their faces, or perhaps that's only the opinion of Jof, who's ever the optimist. But if they are dancing in a kind of joy, it might be the kind that comes from blissful ignorance, lambs to the slaughter — or it might be the kind that comes from living fully until the last moment.

I don't know what I really think is afoot in those final moments, but while I'll need to rewatch The Seventh Seal at least seven more times to make up my mind (if ever), considering that possibility of epicurean abandon has led me to think about another medieval phenomenon.

Dancing plagues

Historical records also speak of sudden, maybe even "contagious" outbreaks of people, often peasants, dancing in public, sometimes to the point of death. Even without that tragic outcome, the medieval dancing plagues were also a source of consternation with the decidedly un-Christian indecencies that would often transpire in their midst, and with dancing itself sometimes being condemned for its vanity, frivolity, or what have you.

Compared to the rise of the danse macabre motif in art, there is considerably more scholarly disagreement about what was really causing all the dancing plagues to happen and whether it was really dancing versus cases of mass epilepsy or ergotism, the latter not being completely far-fetched. However, the thing I tend to find most interesting about the dancing plagues is that although they were occasionally documented in centuries before the Black Death, their largest statistics start a few decades afterward. Assuming any sort of psychological basis, I can't help imagining such spontaneous dance-fever in public venues as a delayed, intergenerational reaction to the earlier need to isolate from the real plague.

And people certainly had isolated. Germ theory was five hundred years away, but quarantining was an ancient practice already. It didn't take future scientific instruments for most humans throughout our existence to observe that often if one person fell ill, people who had close contact with them would do the same. Miasma theory — the idea that "foul air" brought disease — was inaccurate, but it held sway for so long because it nearly explained things rather well. Many people in plague-ridden Europe inherently knew they would stay safest through minimizing contact with others, whether by remaining in their homes or (for those with the means) fleeing to less densely populated areas.

Such a flight is the subject of Florentine writer Boccaccio's short story collection known as the Decameron, completed around 1353.[2] However, as Boccaccio experienced the tumult of the Black Death in one of the worst-hit cities, he documented the plague himself and reported how not everyone isolated from one another. Many people would engage in wild, orgiastic gatherings to eat, drink, and be merry before the end they saw as inevitable. Descriptions like these bring to mind the nightmarish scene in Werner Herzog's Nosferatu the Vampyre (1979) as a town wracked by death explodes into similar public partying; the real plague there is a vampire, but the townsfolk don't know any better.

Maybe it was behavior like Boccaccio relayed from Florence that would lay the groundwork for future dancing plagues. Either way, the dancing plagues might not have been especially dangerous besides whatever dehydration, starvation, or crushing was causing people to die — akin to the pitfalls of rave culture — but many people in modern and medieval times alike would probably agree that it's more than a little irresponsible to make merry in large groups during the active spread of a frequently deadly or disabling illness.

It's impossible to write about this subject in 2024 without thinking of the pandemic our species has just endured. But even if "shit never changes" in the instinctive human responses to pestilence, I don't know how many people today really think about why things have stayed so constant. This lack of reflection often made me uncomfortable during covid's height[3]. I obeyed every gathering restriction and I waited to engage in higher-risk activities until I'd been vaccinated; I continue to get vaccinated and I scrutinize large events with poor public health practices; but as someone who experienced severe mental health impacts from isolation, I also did not innately see every person who flaunted gathering restrictions as someone who selfishly thought they were invulnerable to the disease.

People who made such choices were certainly acting out of self-interest — they were hardly altruistic — but they didn't always have privilege in their situation. I knew and heard of many people who were fully aware they would be more likely to die of the disease if they caught it, and they took few precautions because they already expected their lives to be short enough that there was no point (in their minds) treading on eggshells. Alternately, they were seemingly not more likely to die than their peers, but they were chronically disadvantaged in other ways that drove them to despair. They asked, "Why should I limit what few pleasures I already have?" and acted accordingly. It reminds me of what I've heard from queer elders about the peak of the AIDS pandemic in North America; as lovers and friends and chosen family died in droves, some of our people took extreme precautions and became utterly sexless, but others felt so hopeless they continued to engage in the same sexual activities they always had (or even increased) because it was all they had left.

For my part, I definitely prefer to reduce disease transmission rather than go out of my way to do anything that will make it more likely. Hence my own chosen behaviors during the covid pandemic. However, I thought about the desperate/despairing party-goers very often. Embracing ecstatic ritual practice does not have to mean following their example, but I do think it should mean recognizing the humanity/human-ness of people who take such risks to feel alive despite the threat of death. Much of the old "normal" from before covid deserves to pass away, and not enough actually has; simultaneously, the destruction of communal festivities is something I also believe we are morally obligated to prevent,[4] even if we can still debate whether conditions are currently safe for certain festivities to resume.

Ecstatic defiance

As for how to resolve that debate — where to draw the line about what is now safe vs. unsafe degrees of socialization and what precautions people should take — I really don't have useful thoughts here, because I'm often torn. Really I just couldn't write about the danse macabre without acknowledging the Black Death's modern (though not totally comparable) analogue. I am not offering the danse macabre as a statement about covid. Rather, I offer it as a means of widely considering what I'll call ecstatic defiance.

This is found in Emma Goldman's statement that's frequently reduced down to "if I can't dance, it's not my revolution":

I did not believe that a Cause which stood for a beautiful ideal, for anarchism, for release and freedom from convention and prejudice, should demand the denial of life and joy. I insisted that our Cause could not expect me to become a nun and that the movement would not be turned into a cloister. If it meant that, I did not want it.

It is also found in the motto of the 1912 Lawrence textile strike: "Give us bread, but give us roses!"

The original intent behind the danse macabre might have been to induce humility before death, demanding Christian penitence from the viewer. But looking back at it now — and perhaps even to some audiences centuries ago — I think the imagery suggests we need to conduct our lives in more than a state of fear; if we become only fear, we are lost. As death takes our hand, we can still dance.

I have not come close to death this week, but I have thought about it very closely, in more ways than one, and I've wept. I've spent hours as a shell. Lord — my lord of the wood and the wild — let me find the rhythm in my feet again.

I don't wanna end like this (Cataclysm)

But the sting in the way you kiss me (Armageddon)

Something within your eyes

Said it could be the last time

'Fore it's over

Just wanna be, wanna bewitch you in the moonlight

Just wanna be, I wanna bewitch you all night

Just wanna be, I wanna bewitch you one last time in the ancient rite

Just wanna be, I wanna bewitch you all night

— "Dance Macabre," Ghost

[1] Of course, the Black Death did not only impact Europe and most likely began somewhere that by modern geographical standards would not be classified as "Europe," rather Central Asia. However, evidence of a pan-Eurasian plague outbreak is lacking. Death statistics in Asia (and Africa) are essentially recorded for anything encircling the Mediterranean, not further east or south. That said, the mortality rates were similar to Europe, so this is something I have to remind myself about before I grow too enthusiastically convinced that the Black Death singlehandedly completed Christian Europe's slide into colonial expansion and capitalism; what Europe also experienced over the following centuries, unlike in surrounding regions, was the Protestant Reformation.

[2] Disclaimer: I haven't read it, but would like to.

[3] Not that covid is gone, and not that statistics are being reported accurately, but I do choose to believe that case rates are now far lower than a few years ago.

[4] Having just said this, I do want to emphasize that I'm thinking of genuinely enriching, sustainable gatherings. I'm not going to argue that Disneyworld has the right to exist or that massively carbon-dumping conventions, music festivals, etc. should just continue with business as usual. But this is ecological common sense.

Thank you for reading this. If my own spirits still aren't perfectly elevated after writing it, I've at least given myself something to also read and reread, forcing myself to remember my own vows. I have my grief and my fear and my despair, yet the rhythm of the dance compels me.

Next week, I'm going to have a small treatise on the ideologies (plural) of survivalism; and the following week will be an examination of divination through palmistry, not as something I practice but as something I used to and still think about at times, with a skeptical curiosity.

Member discussion