Last Quarter: Healing from loneliness

Hello. It's Friday. Unlike some weeks, I'm prepared to dive right in to the meat of my meditations. Be warned only that what I'm writing about today may stir difficult emotions in you, and perhaps also for me as I go. And yet as Last Quarter posts go, I will be describing something that is in the end very positive.

At first I have to work through the initial problem, which is a screaming, starving, traumatic loneliness; then there is the approach I've been taking to undo it in myself. That approach is an intentional process of changing how I engage with the very fabric of the universe — shedding ideas and tendencies from the culture of my upbringing, which have been so deeply ingrained that despite spending most of my life intellectually rejecting the socioeconomic models by which that culture operates, I was still caught in certain psychological patterns that are significant side effects of being raised in those models, or being raised by people who were affected by them as well. Now I do not quite feel free; but I feel many bonds loosening, and perhaps some are even broken. I know what freedom from loneliness may be like, and I know that the loneliness is artificially imposed.

It's worth noting up front that my journey has not been about moving from negativity to "the power of positive of thinking." There has been no "law of attraction" or "manifesting" here. I have not become less lonely by figuring out a magical technique (or charismatic manipulation) to draw more people into my personal orbit. Orbit would be very much the wrong word here. I am not the center of the universe, and nothing is. What I've been trying to accomplish — and starting to succeed at — is to recognize my place in an infinite network where many connections already exist, where more can be formed if mutual efforts are made, and to both work and hope for a life where any non-interaction between myself and a neighboring node is actually an equitable, deliberate protocol rather than a simple failure to communicate. The increasingly trendy but very accurate and powerful phrase to describe my goal is "living in relation."

But before the solution, there is the problem, as warned.

Abandonment & avoidance

My sibling, less than two years younger than me, was probably the only real, close friend I had until I was nine years old. My earliest school years were enjoyable when it came to learning new things (with a few stubborn exceptions), but not when it came to socialization. When I interacted with other children, either we couldn't connect beyond a very temporary situation or I would get bullied, in the latter case sometimes by a couple of classmates who simultaneously tolerated me in their sphere but not really to my own benefit. And even when I turned nine, I made a friend who was just as isolated as I was, and we formed a weird duo whose association was not particularly understood by anybody else, and whose obsessions were largely mocked, and whose emotional dynamic was still not balanced enough to last after elementary school.

It took going to a "gifted and talented" summer camp during my teenage years — as well as venturing onto my first web forums and chat rooms — for me to have friendship rapidly extended my way, and for me to learn how to not only accept and maintain it but also to take what I learned in those unique spaces and integrate it into my social life during the school year. Maybe it also helped that I had been an old head on young shoulders and suddenly everyone else was growing up around me, too, so I didn't seem as strange and I felt more like I could let my guard down.

Even then, though, my friendships never felt completely satisfying. I changed summer camp locations over several years, losing track of people each time, and my online friendships were emotionally and intellectually significant but lacked the dimension of getting to share offline activities together; and my new friends in school were real, but I was never anybody's best friend, luckily bullied less and less but still circling just outside the crux of any one friend group, a second or third or even fourth thought. And like anyone at that age, I made my share of stupid mistakes that made some people who liked me previously not like me so much anymore.

I was also never asked out on dates, and I always had the few attempts I made rejected. To be fair, I was in passionate first love with an online boyfriend for a couple of years, and during our one parentally-sanctioned rendezvous he became my first kiss as well as a few other stops on the proverbial baseball diamond; but I ultimately ended things because (among other reasons) I was working in a monogamous framework and had struggled repeatedly with having my heart tugged by people much physically closer to me, and I knew I wasn't going to be able to hold out for additional years of high school and college without committing some youthful infidelity. For a while I quietly but bitterly regretted my choice when it seemed like I had thrown away a guarantee for a small string of people who didn't have any such interest in me.

It might have been easier to cope with if by that point I weren't also living with divorced parents, one of whom was highly emotionally distant. Intimacy was so foreign that to encounter it anywhere, romantically or not, felt like water in the desert; I grew quickly responsive to whoever seemed to like me and want to get to know me better, and sometimes I'm astonished I didn't get into more trouble than I eventually would after I left home.[1]

So far, what I've described is somewhat common for a queer and gender-nonconforming child, but even moreso for a classic autistic childhood, especially for an undiagnosed, high-masking autistic girl. Before I write about what came afterward, I have to pause and ask myself for the thousandth time: how many of my challenges resulted from my autism interfering (in a genuinely negative way) with the self-expression, emotional regulation, patience, and receptivity that are all necessary for forming good relationships with other people? And how many of my challenges resulted from other people unfairly ignoring my potential value as a friend or partner because of how I failed to conform to the neurotypical guidelines created by white capitalist hegemony?

But I can step back further and ask how many of my challenges also stemmed from how the Western educational system may inherently make learning healthy social skills more difficult, fueling the false introvert/extravert dichotomy between "smart but withdrawn people" and "outgoing but stupid people"[2]? What stemmed from something similar to but much more destructive than my autism, which is societal individualism or atomism, the general expectation that every human is an island who ought to be able to do everything themselves — meaning that in school we are taught various cognitive or physical skills and pieces of information, but we're almost never taught empathy, respect, collaboration, or solidarity, instead expected to naturally pick that up among our peers or be taught by parents and religious leaders, even though there is such constant interruption (for us and for them) by capitalist demands that we not empathize, respect, collaborate? My autism is assuredly material, not purely a cultural construct, but how many of my early social problems would have existed if I had grown up in an environment where I was given more chances to meaningfully overcome autism's real social downsides, and where everyone around me was more immediately inclined to kindness instead of competition?

I'll come back to this later on, but let it suffice to say initially I believe the answers to all these questions are bound up in each other, and that in my childhood loneliness I dealt with something that is not unique to autistic people; autism both makes it exceptionally difficult to overcome and then, as I'll get to, paradoxically helps for finding the way out.

Whatever the case, meanwhile I reached my early adulthood with lasting effects. I was not traumatized socially by any singular, massive incident — not the way I was traumatized by things like my uncle's suicide, my parents' divorce, or the September 11th attacks[3] — but loneliness is a trauma because humans are a social species who can and do die faster when we lack strong ties to each other. And as my loneliness fluctuated but ultimately compounded over the course of nineteen years, by the time I met the young woman who would emotionally, financially, and sexually abuse me for two and a half years, I was in a severely vulnerable position. Her abuse further reinforced my loneliness because of my university social life that she singlehandedly destroyed through isolating me. But even if I hadn't met her, a good deal of damage had already happened earlier in my life, stunting my psyche; indeed, though it was never my fault that she hurt me, I would never have tolerated it as long as I did if I hadn't been afraid to lose the closest non-familial relationship I'd ever had.

I did escape, but for at least a decade afterward I struggled to heal. More precisely, even though I found myself in a highly rewarding new partnership and marriage, once I recovered from the abuse itself I still struggled to make any progress at improving my interpersonal skills beyond the point where it had been arrested in my early 20s. In my marriage, despite how loving and stable we generally were, I became repeatedly terrified that I would either be abandoned on an emotional level that led to similar mistreatment as had happened before, or abandoned on all levels as I was surely destined to never have someone really care about me as much as I cared about them. I even meta-worried that my anxieties and efforts to keep things stable would themselves drive my owner away.

And as much as I developed what psychologists would call an anxious attachment pattern on that front — unable to recognize just how safe the relationship actually was — with my eggs all in one emotional basket I found myself in avoidant or disordered attachment with others. I couldn't be lonely or feel abandoned if I didn't let myself get too invested in anyone. I should leave places that were uncomfortable before they could beat me down. I separated myself repeatedly from a few adult social spheres, the first because of getting burnt out on others' immature behaviors, the next because I felt like they wanted me to be a "geek" archetype that I was not, the next because my values and priorities conflicted too much with some of them, and the next because of a serious organizational blowup where sides were taken and I gradually became disillusioned with both. Somewhere amid all that, I ghosted a friend whom I'd previously spoken with every day for years, because not only had they grown stifling but I couldn't bear to work through my problems with them.

Of course, it was right for me to enforce boundaries, but I was also frustrated with myself. Why was it so difficult to find people who saw "the real me" and honored it? Why was it so difficult to find people who I not only liked right away but felt I could trust long-term? Why did it feel like my most frequent interactions with people I knew were taking place on social media and not in situations that were more enriching?

Eventually I settled in the local kink scene, which has so far given me a sense of real belonging, and I don't think I'm ever really going to leave it no matter how wildly dangerous and dramatic it can be. But for a long while, I still felt lonely in odd ways. I would desire emotional (and being nonmonogamous, sometimes sexual) closeness with some people, but that desire would often follow a disappointing pattern: I'd spend a few months or years getting to know someone just well enough that I would grow very excited about how close we could eventually become, only to discover the limits to that potential, sometimes because that other person really wasn't invested in me the same way, but often because they were too busy (or had too many challenges of their own with communication and executive function) to build a stronger connection with me even if they wanted to.

I would know just enough about the rest of their life to grow jealous, because here they were investing that time in other people, and then I would ironically allow my jealousy to inhibit my willingness to stay connected. "They don't care about me the way I care about them, so I suppose I shouldn't care about them at all." Luckily I managed to not walk away from everyone this happened with, but I knew something was wrong. I felt poisoned inside.

And all the while, I'd been tolerating a couple of unhealthy friendships inside and outside the kink scene for years and years and years, because I still wasn't completely familiar with what a positive one looked like. All told, my social life finally looked excellent at first glance, but somehow even in my early 30s I was simultaneously allowing myself to spend too much time on people who shouldn't have mattered, and fretting myself sick about not getting to spend enough time with the people I wanted to. I had a very strong sense of my own identity and interests, but little sense of getting to share that with others, except the exceptionally tiny number of people who felt close enough I was petrified of losing them. I wasn't adrift, however I felt like I was anchored somewhere with other beings drifting around me, and like my only options with them were to shut down or pine forever for the impossible.

Abandonment pathologies on the individual scale

In a Western clinical sense, what I'm describing may not only feel familiar to other autistic people but also to people who have received a diagnosis of either borderline personality disorder or complex PTSD (C-PTSD).

Periodically I've feared "being borderline" because of how damaging the condition really is to people who enter that personality's path, including myself as my abuser ticked nearly every borderline box there is; I've been afraid of becoming like her. I've also feared "being borderline" because of how exceptionally stigmatized the condition is for people perceived as female. However, trustworthy therapists have reassured me repeatedly that I've grappled with something much more like C-PTSD. Compared to typical borderline behaviors, I have an evolving but non-volatile worldview, good impulse control, few dissociative episodes, and a tendency to move slowly in relationships rather than to rush into them. My sense of self has been in flux, which can be considered more of a borderline trait, but the fluidity has largely involved gender and not much else; I've also stabilized my identity through the natural course of growing up, without needing deliberate intervention. My attachment patterns have definitely been a mess, and I'm not proud of my moments where I've ghosted, unfairly mistrusted, or grown possessive of people; but as far as I've been aware, I've never stalked, manipulated, or lashed out at people, never "split" my perceptions of them to switch violently between love or hatred. I keep my turmoil to myself, basically, and that's considered much more of a C-PTSD trait.

But of course, that is still not exactly an easy way to live, and I know for a fact that C-PTSD has sometimes made me difficult to live around, and I'm lucky my marriage these days is not only intact but on the upswing. I know some people can still find me weirdly aloof, too, and they probably haven't even realized the half of it, only that I'm a person with a busy social calendar who nonetheless needs a lot of time and positive experiences to let myself reveal vulnerabilities. Most of all, I believe that it's vital for me to mind my potential "tipping points" into a borderline personality pattern, because as far as I'm concerned the two separate diagnoses describe behaviors that largely stem from the same source: abandonment, neglect, loneliness a sense of having no one else really looking out for you. How our minds respond to that accumulated stress is governed by factors so complex that it can nearly seem like a roll of the dice which condition we're destined to develop.

And as I discussed already, autism muddies the waters further. It could partly be the foundation of some of my social difficulties in adulthood; but not everything that I struggle to do is automatically from trauma. Trauma is something to heal from, too, whereas autism is not. I will always be autistic. I will always have some ill-understood but genuine neurological distinction that makes my focus on the world tend toward the monotropic. I don't have to "split" in the borderline sense to still leap more toward judgment than neutral perception: a person may be wildly interesting to me, or quite boring/off-putting, with not that much in between. This might always inhibit my ability to form friendships or other relationships, even though I fundamentally prefer to be with other people than to be alone.

But now I've wallowed enough in this post. A few years ago, I started to un-fuck myself. As the world entered pandemic lockdowns, as people all across this society suddenly became even more isolated than we already were, I realized how dangerous that would be to my mental health. I complied with gathering restrictions, but I resolved to invest more time in the relationships I wanted to have, first remotely and then in person as it became safer to do so.

I started to text people I deeply cared about just to catch up, instead of relying on social media for that purpose; I started to plan more private get-togethers, digital or physical, where I could be confident that people who mattered to me were present, instead of showing up at public events (or events hosted by other people) where I had to hope a connection with someone might get nurtured for a few hours; I started to take joy in any amount of interaction that I got to have with someone I liked, even if they were interacting with other people more than me; I started to tell people directly how much they matter to me, instead of hoping they'd read my mind; I started to trust that if I liked someone, the feeling itself wasn't a one-way ticket to disappointment. In tandem, I'm now asserting and maintaining better boundaries around interactions with the people I don't like that much, but this looks much different than tolerating someone for a while and then ghosting them — it's more like keeping certain people at arm's length from the start, and not feeling tempted to let them close because I'm satisfyingly busy enough with others.

And yet, all of this is not the actual solution I found to my loneliness. I've described concrete steps I took, but the real change has been in something so much bigger than any one relationship or even any one social sphere. I feel as if I've been learning to stop thinking of myself as a singular individual whose needs and wants are absolutely my own. I've been consensually dissolving the edges of my selfhood, learning to tolerate the intrusions of another's will. The first place I began to learn this was years ago with my owner, and unsurprisingly it was my marriage that improved before the rest of my peer relationships did; yet at some point I discovered this skill matters not only for a D/s relationship but for existing comfortably in the universe.

I can speak about personal trauma, personal neurodivergence, and their roles in forming personal pathological behaviors, but we all live within such a complex social system that no matter the specifics of what I've struggled with, I also feel keenly aware of how virtually any human within this system must feel the struggle of loneliness — and how the struggle runs deeper than trauma, deeper than brain wiring. It's in the ideological fabric of white, Euro-colonial, capitalist, Christian hegemonic civilization.

Relation-makers, relation-destroyers

Humans began by relating. If there is a "human nature," that's all it is. Like any species, we can only survive in our environments by fostering close relations with what's there — by knowing it, letting the parts of it that are outside ourselves influence our choices for how to behave, and giving some part of ourselves to our surroundings to help maintain it. As a social species, we also relate to each other very heavily, generating knowledge and furthering our survival as a group effort. As a tool-using species, we can take more from an ecosystem than most species can, and we can also give back more; we can transform our environments with exponentially more impact, and if we are wise and careful that impact produces greater abundance, not less. And as a heavily linguistic species, we can tell stories and preserve stunning amounts of information to help us foster the best possible relations in the future. Our species' earliest and ongoing indigenous ritual practices have reflected these realities, using animistic concepts to help successive generations grasp how their lands and seasons work, how to flourish, what to do, what not to do.

The less that we live in good relation with each other and our environment, the less we can depend on those things, and past a certain point our only route is death. Similarly, the more we insist on doing things completely alone, the more likely we'll forget how to stay in good relation with other beings. This is why empires never last and also why no empire is beneficial; indeed, this is why centralization of any kind will always collapse at some point, and why trying to concentrate instead of distribute power always hurts someone or something. It wasn't a mistake for humans to invent agriculture or adopt less nomadic lifestyles, but any time we give in to the extractive instinct that the land is there for us to take what we please, unidirectional and entropic, then we go through one more cycle of a few elites hoarding resources until they run out where they are and have to reach out further, then again, then again, and then at the point of maximum instability there's collapse.

This mistake has happened probably more times in human history than we will ever know, let alone be able to count. However, for a very long while, there were technological limits on just how far we could afford to push ourselves out of relation with the earth or one another. An empire could only grow so large, and the same for a war. And even when catastrophes occurred — such as how humans did probably cause the extinction of most planetary megafauna through overhunting in the Stone Age — animist beliefs and stories helped to specifically preserve memories of those mistakes with lessons to avoid repeating them.

As I've written of in this newsletter before, we're in the state we are today because of a perfect storm of spiraling developments that have brewed for a few thousand years. It didn't particularly have to take place in Europe, but that's how the coincidences shook out. A standard round of empire-building ran its course with Rome, but even as the collapse played out similarly to so many others, it coincided with the explosion of a new religion that though perhaps once espousing a liberatory theology for the sake of colonized Jews was now wedded with Roman power structures and Platonist philosophy about elite meritocracies. This religion's proselytism did not destroy the animist belief systems of Europe overnight, but it created a strange overlay among lower classes, interrupting the stories they had originally told each other, and among the upper classes it was a tool of new empire. Plague then came, killed half the humans on the continent, traumatized them on a social scale that has possibly never been witnessed at any other point in history, and created so many voids in the already parasitic feudal social order that worse opportunists took hold and merged it with the existing merchant class to create the capitalists. The common land on which most people lived was torn out from under them and privatized; a new form of the existing religion emerged which particularly emphasized the filth and squalor of the material world compared to the purity and separateness of heaven; the development of free, good sciences was marred by entanglement with economic pressures, the need for a clockwork, transactional universe free of non-human (and non-white) agents; industry emerged. Europeans' right to relation was stripped away, and then through colonialism this became everyone else's problem, a thousandfold.

Most humans now live under a paradigm (either directly or through external influence) where relations are meant to be severed. You are not meant to understand or touch the land beyond what is necessary to remove something from it — something which will never be put back. You are not meant to love or care for anyone but yourself; the modern mantra of self-care is deceptive, demanding that you prioritize yourself so extremely that somehow, over and over again, actually having a life that involves anyone else sounds just a bit too exhausting. And of course it really is exhausting when your job grinds you to the bone. No wonder it's so tempting to ask people to pay us for casual emotional labor, instead of working to build communities where transactional payments don't need to exist.

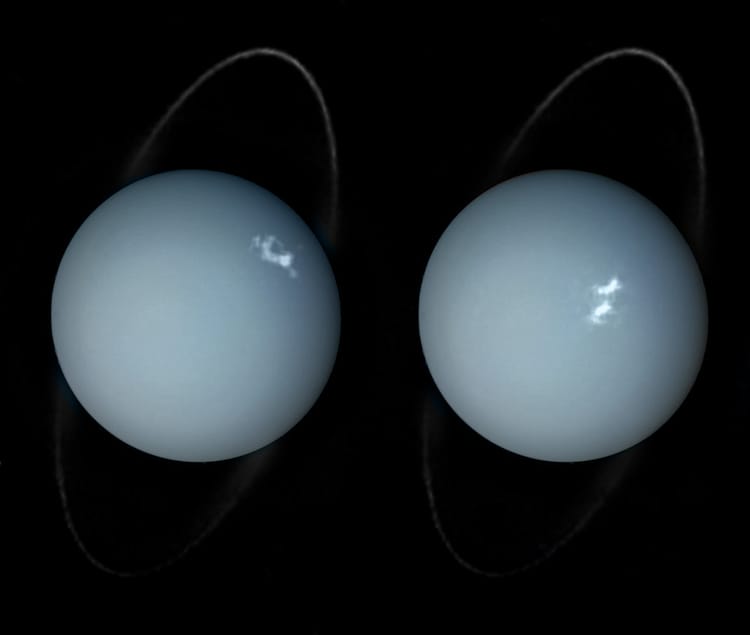

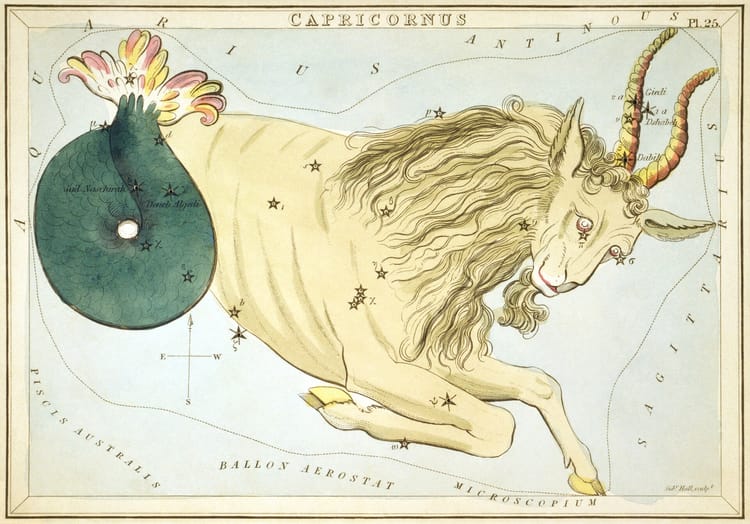

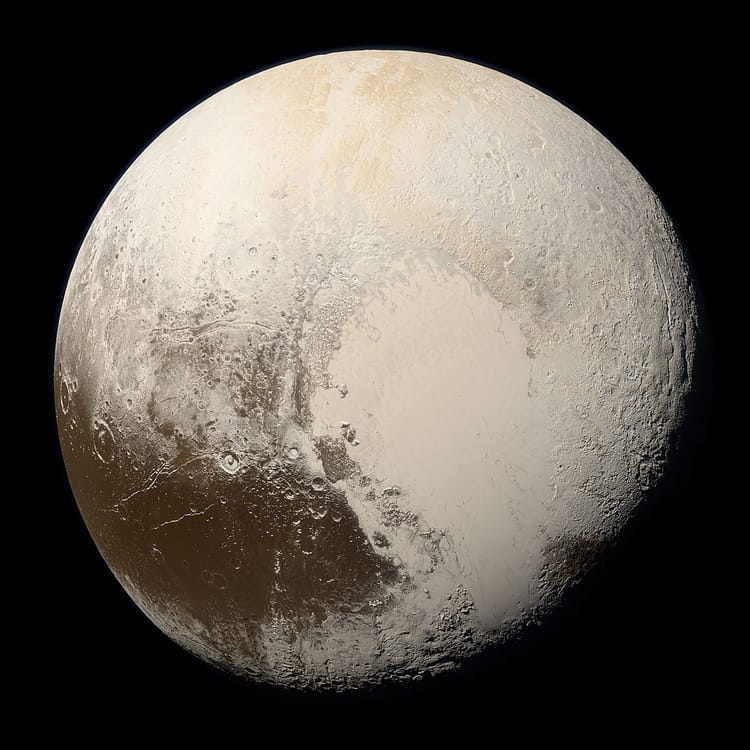

Once our species was rife with gift economies, but no more. And disturbingly fewer and fewer people know anything about their local biospheres. Fewer people know what stars should be overhead on a given night, even if they could see any. Fewer people know what phase the Moon is even in. Fewer people have any social environments to congregate in besides their own homes, if those homes even have room. Fewer people have two-way, lengthy conversations instead of absorbing someone's opinions that have been blasted into an online void, and occasionally blasting their opinion back. Fewer people trust their neighbors or even know their names. Fewer people are having sex. Fewer people are having children even if they'd like to, because they know they don't have a care network to help raise those children. Fewer people are happy. Our disconnect with the earth is reflected point for point by our disconnect with ourselves.

It is as if our instinctive gift for relation-making has lost against a relation-destroying virus. With all that in mind, I sometimes worry that my autism could be a bad thing — do I have an excessively modern, colonized brain, insisting on rigidity and control and schedules and taking life one tiny parcel of a thing at a time because the totality, the complexity, the ambiguity is otherwise too much?

Well, maybe some contemporary manifestations of autism are prone to falling into traps like that. But when I've really meditated on my autistic experience and on the things I hear from other autistic people, not only am I convinced that we've been a part of human communities forever, I'm also certain we are often among the most adept system thinkers, pattern recognizers, and thus relation-makers. There's even no harm in being a strict schedule-minder if the schedule being kept is the Wheel of the Year — as long as we learn to account for that wheel's slow, ideally gentle changes.

My un-loneliness today

When I started un-fucking myself, I was following good instincts about what actions to take, but after a slow burn for the first couple years I made progress in leaps and bounds once I started to consciously understand that I was pursuing a more relational way of living. I can thank writers and thinkers whose work I've been immersed in lately and reference here periodically — Yunkaporta, Rasmussen, Kimmerer, Graeber, for example. However, what excites me is not just reading things and undertaking loose "self-improvement" therefrom; I am not trying to be a better person, only to be a person who dwells in the right place. In all senses of dwelling, all senses of rightness, all senses of place.

This has particularly helped to guide me through becoming less lonely. I cannot be lonely if I'm in good relation. And being in good relation does require a lot of work, but it's work that feels rewarding. I am not disinterested in being loved, but the act of loving feels just as beautiful. I do not need to feed a hurting ego, because there's less of an ego — or perhaps it's that I feel my ego spreading beyond the bounds of my body. I feel understood by what's meant to understand me. I am not worried about being understood by things whose relation to me is of formal avoidance.

If all of this is starting to sound a bit arcane, don't worry — I'm going to unpack it in the months to come. This is part one of many. Like me, and like you.

[1] Especially from how I was an early bloomer in adolescence and so verbally articulate. I was being offered alcohol by waitstaff by the time I was sixteen and I regularly surprised (and possibly worried) fellow online denizens by revealing my age. I had a few interactions with older men, both in person and digitally, that were nowhere near as inappropriate as they could have become, but which still were dangerous insofar as I had no idea what the risk was at the time and we should absolutely not have been in those situations.

[2] At this point I describe myself as an extravert out of a certain contrarian spirit, but I would rather we move past this binary entirely.

[3] Or their nationalistic aftermath with its long-lasting sociopolitical consequences today.

Thank you for reading. Next week's post concerns the Devil represented as Pan; the week afterward there will be a post for paid subscribers only on my first psychedelic experience.

Member discussion