Last Quarter: On heat deaths of universes

Hello again.

I've designed a kind of cyclical writing prompt pattern to help me post here every week without talking about the same type of subject matter for several weeks in a row. It's not at all coincidental that the pattern I have in mind is aligned with moon phases. Much is misunderstood about moon phases; sample myths which come to mind are the unproven notion that people who menstruate have evolved to do so because of the moon's phase, or the equally unproven notion that the moon's tidal effect has an influence on agriculture beyond the macro-effect of sea tides on their attached rivers and the flood plains thereof. Nevertheless, I think it means something that people want to attach significance to what the moon is doing, and I find increasing peace in measuring my life by the moon as well as by the sun.

I intend to write a later piece with expanded thoughts on the insufficiently rationalized beliefs that people have about the moon, and the ways in which I can see them being absolutely inaccurate versus correct from a slanted perspective. For now, I'm only going to note very briefly that as the moon's monthly shifts provide an organic rhythm for pacing different ritual activities and making sure nothing's neglected, my writing pattern here will match that rhythm. Each Friday I will post something whose subject and character is informed by the moon phase that's most recently been reached, as that's where my headspace will be.

Consider these the keywords I'm working with, phase by phase.

- New Moon: ordeal, satanism/occult, mystery, ecstasy

- First Quarter: hedgecraft (incl. tree lore/plant use), hand crafts, domestic work (incl. land stewardship and homesteading)

- Full Moon: divination, astronomy, paganism/living animism, art, fertility

- Last Quarter: mental health, state of the planet/society, death work

There will, I promise, be discussion of kink worked into most if not all of these posts. And there will of course be special extra focuses in posts written near the eight solar holidays that my owner and I observe, and which some readers may also celebrate.

With that, we have recently passed the last quarter, and that seems like an ironically appropriate way to truly begin Salt for the Eclipse: to begin by talking about endings.

For this post, and for any other Last Quarter entries, please consider there to be a blanket content warning about very, very heavy and depressing topics. Even when I don't necessarily offer pessimistic conclusions to these posts — optimism is quite plausible in some cases — I recommend setting this material aside to read on a good day, if you're having a bad one.

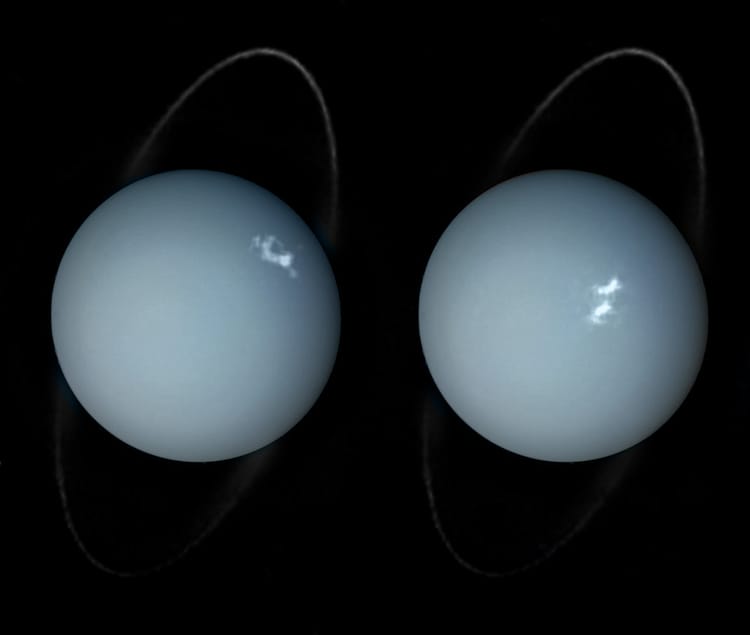

Stargazing

As Chelsea Wolfe has sung: "Simple death feels infinite compared to the end of it all."

I don't remember what age I was when my parents explained death to me, but while I think I was a toddler. It terrified me in the same way that I suspect it terrifies any child who doesn't receive a sugarcoated summary, it would take the violent suicide of a close relative to send me down the road to panic attacks about dying. That traumatic event didn't happen until I was in late elementary school. In the meantime, and therefore for practically my whole life, I was more constantly afraid of something else I'd learned in my toddler years, which was that the very planet on which I lived was going to be destroyed eventually and inevitably by the very star on which life depended growing so large that it would expand and consume several planets in its orbit. I was also afraid of meteors and comets sending us to the same fate as the dinosaurs, but depending on our technological capacity that still seemed preventable, or survivable. The expanding sun was the real horror.

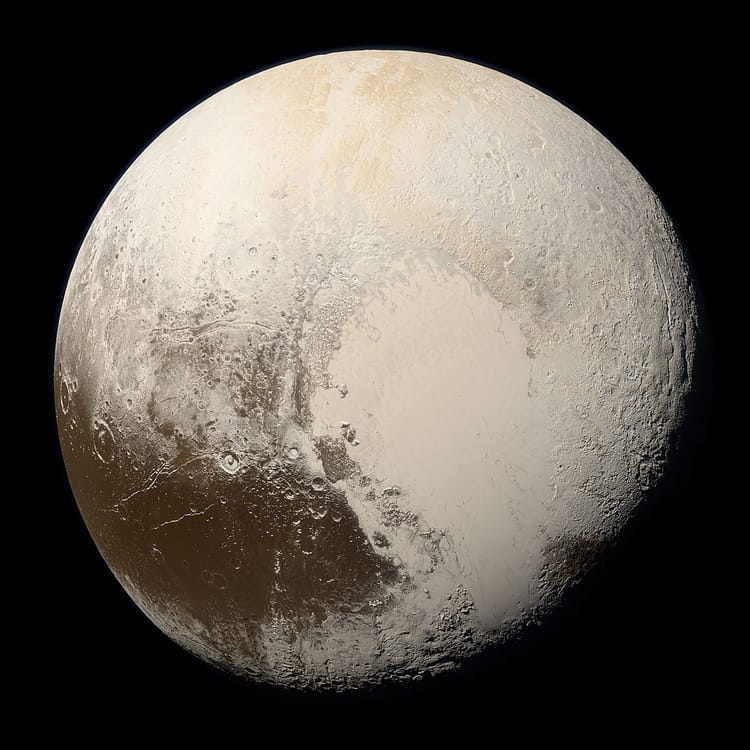

In turn, even if humanity (or whatever form we had by then) managed to escape this apocalyptic event, an equally powerful horror was that unless we ever discover some new, heartening truth through physics or are all given a mass cosmic revelation that in fact there is a benevolent god who controls reality — without these chances, then the universe itself, reality itself, will eventually become completely inhospitable to human life, to all life, even to mere existence. There are competing theories about what exactly will happen, but the "heat death" theory is what I think now carries the most physicists' votes; in this scenario we go not with a bang but a whimper, burning out and fading away, everything in the universe expanding so far away from itself that the only particles can survive being ripped apart are photons, and then I think even those will go. There is quite simply no way for anyone or anything to cheat this final annihilation.

So I was afraid of these inevitabilities in the same way that some children are afraid of going to hell, although I suppose unless you're a Calvinist then if you believe in hell you at least also have the consolation offered by believing in heaven. Somehow I was still utterly in love with outer space. I wanted to be an astronaut for a while, and I ate up anything space-related I could get my hands on. On long car rides at night, I would stargaze out the window and feel like I, despite living in an atheist household, was receiving divine wisdom. But as much as my love for outer space was an authentic and classic neurodivergent special interest, part of me wonders nowadays if my fascination further developed as a way to combat my fears. After all, despite how much I feared my own death, I couldn't get enough of morbid art and learning about topics like poisons, pandemics, murderous cults, and so on.

After all, I was a goth by the time I became a teenager. After all, I was a self-acknowledged kinkster by the time I could legally have sex.

But there was one other thing that over time came to frighten me beyond reckoning, and that created an unholy union of my fear of death and my fear of apocalypse: an apocalypse happening within my own lifetime, potentially therefore the cause of my own death, and this apocalypse namely being something ecological in nature. Like the expansion of the sun and the heat death of the universe, catastrophic ecological change might arise on its own without human involvement; but unlike those other two existential threats, something human-caused was also possible, and in fact ongoing. I feared this not because it was inevitable, but because it wasn't, and yet none of the people with the power to hit the brake were doing much besides hit the accelerator. Somehow we were, and are, facing a heat death of our more localized universe, maybe in a hundred years or less.

A collapse of ecosystems

Since not everyone reading this knows my age: for clarity, I'm 35 right now, and I'm speaking about discovering ecocollapse when I was in preschool. 1990 to 1992. I spent some of my formative years amid a curriculum furor around teaching kids about the awful environmental effects of CFCs on the ozone layer, of oil spills such as the Exxon Valdez, of plastic in the ocean, of deforestation and habitat destruction, of greenhouse gases melting the ice caps, and so on. During this halcyon educational period, I was taught that as potentially cataclysmic as these problems were, everything was going to be all right, because collectively humanity knew what to do and we, the children, would be especially superb ecowarriors. I was overly aware of these challenges, but initially harbored the belief that we would conquer them.

Well, people in my generation may know now that although recycling metal and glass and paper has gone well, plastic recycling is a farce, and the situation with plastic is now even worse than we could have possibly imagined at the time. But in fairness to my educators, I think I was mostly taught the truth. For one thing, in the early 90s we were in a substantially better position to beat runaway global heating than we are today. For another thing, if the momentum in those classrooms were really harnessed by the time we all got out of high school, I think such energy would have accomplished a lot. Instead, unfortunately, come my high school and college years the US (whose environmental policy doesn't need to set the benchmark for other countries, but does have an outsize effect on the actual environment) got the Bush administration, 9/11, and the 2008 financial crisis. My generation couldn't afford to have an eco revolution right then and there, and we were mired in too many flavors of stinking shit which distracted too many of us from managing more than get next paycheck and manage what few, flaky interpersonal bonds The Grindset lets us have.

Then social media happened.

I'm not talking about the original World Wide Web, and I'm not talking about cell phones, and I'm not even talking about smartphones. All of those things have had their own problems, but I think that on the whole their invention has been fairly useful and could be even more useful under the right conditions.

I'm also not necessarily talking about specific online communities that engorged and metastasized with the help of social media. Certainly, though varying somewhat in precise toxicity, social media has either created or nurtured hellscapes including but not limited to "the manosphere," the chans (4 and 8), the "Dark Enlightenment," Qanon, more niche yet pervasive cryptofascist movements, fandom culture, gamer culture, identitarian Vampire's Castle infighting, the neoliberal smugness network, a faction of online leftism I'll generously call larpers, and pedophiles networking to exchange child pornography by entrenching themselves in poorly moderated spaces exemplified by certain corners of anime fandom, furry fandom, and my dear friend FetLife. However, all of these groups are a fairly natural consequence of the socioeconomic circumstances that much of the world is living under.

(The above is to say that violently bigoted conspiracy theorists have existed for far longer than the entire internet's been around; likewise, neoliberalism is always going to do what neoliberalism does; the left's reputation for eating itself has existed for as long as anyone's talked about "the left," even though I admit that as much as I'm tired of leftists jettisoning solidarity for ideology, I'm also tired of leftists who only complain about this and never attempt to actually build back solidarity itself; and I don't wish to actually be dismissive of all gamers, anime fans, furries, kinksters, or anybody who just really passionately cares about certain works of art, partly because I fall into several of these categories and partly because despite my historical cynicism this newsletter is an attempt to describe the world both incisively and compassionately.)

When I bring up social media, I mean specifically engagement-driven social media. I mean the dopamine feedback loop that everyone knows about but nobody talks about but actually everyone talks about but also nobody likes talking about. I mean how phones aren't addictive, and in fact not even notifications by themselves are addictive, but the things that notifications often bring us — endless heartwarming content from strangers, endless horrifying content that we can build up our own egos with to say "look at that awful thing which I would never do," and most of all, attention — are the emotional analogue to heroin, with their own long term effects and overdose risks.

Besides being online since before social media existed, I joined Facebook 17 years ago, early enough that it was only for college students, and I witnessed the introduction of the News Feed first hand. I was slower to join other platforms, as I already disliked what was becoming of Facebook (if it had ever been good) and I could see how most places were using the feed model; I was still partial for a while to social discussion setups like LiveJournal and forums, and in a way I still am, although the people I would want to connect with are usually not there. There are some platforms I've skipped altogether and doubt I'll ever try. But I've tried and left a few places, sometimes after many years and sometimes after just a couple. I deleted Facebook (for a second time) in 2015 and haven't experienced any appreciable loss of anything good in my life. I've also tried and stayed on some other platforms because the benefits actually manage to outweigh the negatives (as with Mastodon and the wider fediverse), or because alternatives for those platforms' functions are still in utero (as with FetLife). I hate engagement-driven social media not for lack of understanding it or for having never fallen prey to what it does. I hate it from direct experience.

In online societies — that is, in cultures who spend a fair amount of time online today — I think we've spent almost 20 years experiencing not only the collapse of our planetary ecosystem(s) but also witnessing normal social communication, our innate human quality, transform into something increasingly unusable. I say normal although it's a loaded word; I have to note that I mean this in the broadest sense possible. Once upon a time, regardless of how much you talked, what method you used to talk (speech, writing, signing, etc.), or how you expressed yourself when you talked, it was a simple fact that nobody in the world would hear or see what you were saying except for people in your very immediate community, unless you were accorded an extremely high status position. The burdens and corruptions of celebrity were real for such people who met that criteria hundreds or thousands of years ago, but there were far fewer of these people than there are today. And I say celebrity also in the broadest sense possible here, because as many an anthropologist or other types of researcher has written before, human beings' brains have not had time to evolve to handle keeping track of more than about a hundred people in their vicinity.

Despite humans now being born with social media handles and e-mail addresses picked out for them already, none of us have ever been psychologically prepared for what being followed by tens (or hundreds) of thousands of people is like. None of us have been accountable to that many people. To be lifted up daily by even just a few hundred people is an impossible rush, of course you would come back for more. To be verbally scourged (never mind threatened) by so many people is an experience so overwhelming that it only makes sense for so many individuals to lash out when it happens to them, even when those individuals very definitely did something terrible and everyone who knew (of) them had their own right to be upset about it. A lot of people haven't even had thousands of negative judgments and death threats flung at them, but they know the prospect is tangible enough that they will tie themselves up in breathtaking knots in order to avoid having that happen to them, or help point the finger at other wrongdoers just to make sure they themselves are blissfully ignored.

Again, I'm not talking about any particular community within this online paradigm. I could talk for ages about how these phenomena affect certain demographics, but I'm still using a very wide angle lens.

Through this lens, I see a planet of people who are unable to solve the eco crisis because even when some of them aren't yet directly suffering from the crisis itself, they are trying to meet the basic human need of socialization while being continuously tricked into "socializing" by the unhealthiest means possible. I'm not exempt from this and I am trying to take a forgiving view toward people who are more immersed in it than me. Almost none of us built this system of interaction, we just tried that cigarette because it was marketed to us. The people who did build all of this are even, I might guess, less malicious about it than the oil companies who willfully covered up evidence about climate collapse in the 1970s. I really try to follow the adage never attribute to malice that which is equally attributable to stupidity and this has spared me from entertaining most truly tinfoily conspiracy theories since the one I did get into for about a week in college (nobody asked, but it was the Loose Change 9/11 truther thing, I apologize). I think even the people in power who are doing really bad things are usually just ignorant of what effect they're having. That doesn't mean they shouldn't be held accountable, but it does create the self-evident truth that if we have social networking platforms generally not being designed with deliberate systems thinking in mind beyond "attract users," how on earth could we trust those designers to program content/suggestion algorithms that wouldn't do something incredibly damaging?

We don't need to worry about an AI like Skynet taking over the world. No program is going to be smart enough to decide humans are a threat which should be eliminated. We have what we already have. It's algorithms with the qualitative awareness of rocks — rocks which have been enchanted to take the already twisted situation of hundreds of millions of people paying inordinately close attention to each other, and then to amplify the agony by orders of magnitude. What gets the most engagement, what delivers the most dopamine, is news and reactions to news. The more horrifying the news, the better, because responding to it is the easiest way to position oneself as a moral superior and receive positive attention from one's followers.

We are a planet of people who are currently paralyzed from stopping the eco crisis because there are approximately one billion other injustices screaming for attention every single day, cut up into 24-hour morsels of misery, and even the people who know about and worry about the planet's ongoing catastrophe are constantly being worn down by 1) the work we do for economic capital, and 2) the work we're now being forced to do for social capital.

The worst part of all is that many of the injustices screaming for attention are completely wretched things that it's good to make sure people know about and take action against. But what happens when we're so inundated by stories about injustices happening at a degree very far removed from our day to day lives?

Atomic warfare

So far, humans seem to have reacted to the online overabundance of news either by losing whatever empathy they ever tenuously held, numb to all others' suffering but their own — or by being consumed wholesale by that empathy until they can no longer accomplish anything in their immediate lives.

Proponents of capitalism and/or government are very fond of arguing that the natural order of things is "survival of the fittest," "every man for himself," and so on — that communism and/or anarchism would never work because humans are too inherently selfish to exhibit the requisite amount of altruism for such alternate systems, or at least we wouldn't do it willingly. At this point I have very complex views about if and how communism and/or anarchism are viable, which will have to wait for another time, but there's one point on which I've never wavered in two decades, which is that no person is an island. We don't merely "live in a society." To be human is to be society.

Except that in industrial capitalism, with 40+ hour workweeks eating half our waking time, and with ourselves as workers divided and destabilized by the employing class, and with the other half of our waking time increasingly caught up in the non-stop online dopamine machine (or harboring actual physical addictions, as the timing of the opioid crisis is not an accident in my opinion), and with public gathering spaces diminishing through the undervaluing of libraries and parks and social clubs, through the shuttering of unique small shops in the face of faceless online ordering giants, and yes, even through lowered church attendance (I'm certainly glad less people are going to most of the churches in question, but religious communities under good circumstances are a valuable emotional support system): we do, increasingly, seem to be living on islands.

No island life was better exemplified than when the covid pandemic started. Animal Crossing: New Horizons released at the perfect time, everyone in the video game commentariat agreed. You couldn't have a "real" life now that you were just supposed to stay indoors forever, so it was time to kick back and simulate a real, cuter life on a magical island where you do have to work a bit to get what you want, and in fact you even still have a landlord, but everyone likes you and anyone you don't like can get kicked out and you can spend fake money on cute fake things.

I actually liked watching my owner play ACNH during its peak, and am completely and hopelessly fond of several of his islanders. I have devoted a questionably high amount of emotional headspace to the likes of blue penguin Sprinkle. Nintendo enthralled me with cute personalities even though I was and am resistant to life sim games. In fact, I'd go so far as to say that despite my sardonic phrasing above, I think even in a post-capitalist world there would be a place for life sims. When designed well, these games can teach children and adults many interesting things about time management, resource management, and social skills. I don't know if ACNH is a perfect example of what I have in mind, but it's a fine game and in certain respects it's superb. What I rankled at with its release was how its indirect marketing appeal was specifically that this could substitute for having flesh-and-blood experiences in your local community with friends, because a pandemic was on.

Of course it couldn't do that. But this was just one straw in the giant pile of straws that covid has been, resting on the camel's back of human socialization under late-capitalist technological conditions. Across social media, as lockdowns began offline, the exultantly smug cry began: I'm an introvert, I've been training for this my entire life. Can someone really say they're an introvert if, when they stay at home and avoid heavy interaction with people outside their home, they still interact 24/7 with people online? I used to think I was an introvert for a long time until I realized that I communicate very comfortably over text, whereas my bandwidth for going out to socialize isn't sapped because of the socializing but because of the scheduling effort involved. But I run into a lot of people who seem to be in my own boat and yet haven't made this realization.

Leaving aside the fact that the introvert/extravert dichotomy isn't even a real thing, there's a privileging of introversion in the highly-online mindset that troubles me. Not so much because extraversion is written off as shallow or "normie," but rather because of the archetype of the introvert being someone who thrives best on their own, for whom social interaction is taxing rather than restorative, for whom trusting people is difficult. This isn't so different from what many people describe as toxic masculinity, the difference being only that it's a "going-it-alone" hypervigilant attitude for all genders, or for people who don't put Punisher logos and blue line flags on their rear windshields.

Coming back to the introvert/extravert dichotomy not being real, I want to note that although I'm critical of the introvert archetype itself, I sympathize with people who genuinely find it difficult to socialize, whether in person or online. Even knowing I benefit from socializing — my anxiety always gets worse when I'm alone or haven't been able to see too many people for a while — at the end of the day I'm still a neurodivergent person for whom dealing with other human beings can be supremely frustrating and misanthropy-inducing if I don't have some baseline level of trust established between us. I didn't know how to make friends until I was in junior high, and I still can tell that I give off some sort of aloof air that suggests other people shouldn't try to get too close to me, even when I'd like them to. It's not a far leap for me to imagine someone else, for whom the emotional payoff of socialization isn't even that necessary, finding the mental and emotional calculus too overwhelming to be worth it, and thus tending to withdraw from the situations where that calculus is required. Even if that's not my own challenge, I understand why it would be yours. You're entitled to make your own choices and prioritize your own needs in that regard.

For people in those shoes, I could see why living in pandemic lockdown would at least be a neutral experience if not in some ways a positive one. And I likewise recognize the people for whom even without a pandemic their physical and/or mental health prevents them from spending time outside their homes even when they'd like to. I'm grateful that the pandemic has generated a boom in better approximations for physical social contact via digital means, and in normalizing virtual hangouts and meetings, because that helps many disabled and immunocompromised individuals out in a way that they weren't helped before. It even directly helps me see friends more, with my own needs. I hope we don't lose such changes.

But those are not the changes that worry me about the pandemic's effects on human socialization. Those positive changes toward accessibility and diversity-of-socialization are material. What's been concerning me is something about the islandness of the conditions under which those changes have occurred.

The atomization.

Among my other apocalyptic fears, I wouldn't rule out nuclear armageddon as one of them, made recently more potent by the war in Ukraine. Nevertheless, that kind of atomic warfare doesn't concern me as immediately as the social bonds which are being increasingly severed between humans in general, making each of us atoms, forcing us to consider ourselves alone.

Under such conditions, mistrust rules the day more than ever. Trauma perpetuates itself, turns survivors into new abusers within all political alignments. We have become so touch-starved, literally or metaphorically, but any attempt to interact with other people seems increasingly vile, because the methods of sustaining that interaction feel cheap and unsafe and rife with surveilling each others' behavior. We are so lonely, and angry about being lonely, and all that so many of us can do is look for the engagement we hate. We are performing psychological splitting en masse. I saw the need for pandemic lockdowns, and followed their rules, and have been disappointed by how governments didn't even do enough to properly stop covid from destroying as many lives and livelihoods as it has; but all this time I've simultaneously mourned how so many people have been denied certain communal experiences together for more than two years now, fueling our atomization even further.

And into these stranded atoms steps a unifying force, not that of cross-demographic solidarity, but that of fascism.

If fascism is capitalism in crisis, what arises during planetary crisis?

This is an open question. I believe that fascism is capitalism in crisis, but that it also comes from something more. I think it comes from sheer despair. People who feel let down by absolutely everything and let that despair coagulate inside of them and transmutate into utter hatred. Many white, cisgender men become fascists without ever being impoverished, because for them it's the end result of violent patriarchal conditioning. Many people of other demographics also wind up supporting outright fascist or generally authoritarian political leaders because they haven't been supported in good faith by alternatives on the left and they've lost hope in asking for that support. All of these people are atomized to such an extent that, as identity is formed in relation to other people, they have no identity, and fascism arrives to tell them what they are, which is an identity explicitly defined by not being something bad.

It's fashionable now on the anti-technologist left to jokingly or non-jokingly idolize Ted Kaczynski, the Unabomber. I suspect that if I read his manifesto, I'd agree with a large portion of what he was trying to communicate, or at least whatever would naturally follow from the oft-quoted opening statement: "The Industrial Revolution and its consequences have been a disaster for the human race." At the same time, though, everything I've ever read about Kaczynski leads me to understand that he was only slightly less of a right-wing reactionary than Charles Manson was. I might read his manifesto sometime in order to have an informed opinion, but I don't trust it.

In turn, I think this is another reason why some other section of the left doesn't know what to really do about saving the planet. Many leftists are afraid, and reasonably so, of turning into ecofascists, or of letting ecofascists into our midst. It doesn't really matter that ecofascism is a little difficult to define — it could mean people who think we need to reduce the human population through eugenics, it could mean people who think the "decadence" of things like queer and trans identity have torn us away from nature, it could mean people who think we should live tribally and "primitively" along racially/ethnically delinated lines, or some combination of these things, or more. Whatever ecofascism implies, though, I would certainly like nothing to do with individuals who could ever deserve that label.

The ecofascist may correctly understand that humans have divorced ourselves from living in harmony with the environment, that humans have not evolved to endure global communication and connection, that we need to downsize many aspects of our lives if we want to survive the coming ecological conditions and ideally improve them. But the ecofascist's hypothetical solutions are not solutions at all — only a violating, bigoted symptom of the thing that's brought us to this precipice in the first place.

Who's the real culprit: technology, profit, scarcity, Christianity, or something else?

To ask who's the real culprit is a way of asking what needs to be eliminated, or counterbalanced, in order to solve the problem at hand.

If technology were the root of our collapsing planetary and social ecosystems, would removing specific technology (or all technology) help? Or would we simply need to invent different, better technology? I feel as if my answer to this question is paradoxically yes, on all those fronts, and also no. It was only by technological advancements that humans became able to poison the planet in the ways that certain humans are willfully allowing to happen. It was only by technological advancements that we've reached this absurd state of online communication. Industrialization incontrovertibly has torn humans away from the land. And yet, one beauty of humans is that we are tool users. I think to deny our ability to design tools would be to deny our own existence. We certainly must make technology. How much technology we should get rid of is an interesting thing to consider, though. And perhaps the guiding principle for technology is, cliché though it's become, Jeff Goldblum asking us whether in addition to thinking about the fact that scientists could create something, did they think about if they should. I like to imagine a society in which most technology development has gone into things like medicine, universal accessibility aids, protecting people from disasters, producing and storing good food, storing information, providing entertainment, and traveling for sheer leisure. There are a lot of other technological developments that fall outside these categories that I don't think we need, even without capitalism as an intermediary. As for that...

If the profit motive that underpins capitalism were the root of collapse, would overthrowing capitalism help? Undoubtedly, but we're under an impossible time pressure where the planetary ecosystem is concerned. If we found a way to destroy capitalism rapidly, we might not have a replacement structure properly worked out, and then our societies in the years to come would suffer slightly less than if capital still reigned, but only by so much. Conversely, the kind of replacement structure that might get worked out in a pinch is more likely to become authoritarian in its own ways, and I can't summon much enthusiasm for that. I think we certainly must get out from under capitalism as much as we can, and not delude ourselves any further about simply reforming it (reforming the profit motive is not possible, profit is destructive by definition); but will we have the chance to prove that a new world could truly rise from the ashes of the old? I don't know.

If artificial scarcity were the root of collapse, could we simply inform everyone in the world of the abundance we really have, and prove that altruistic societal organization is possible because there was never any reason to act selfishly? Maybe, but I think we are again nearly out of time. As the eco crisis worsens, more resources are becoming genuinely scarcer, and there may not be a way to equitably distribute them according to the world's needs — not because people would never be willing to do so under real scarcity, but because if a resource disappears altogether, you can't share around what doesn't even exist.

If Christianity were the root of collapse — and some people do think this, because ideological Christianity was an active symptom of the Roman colonization which first created the de-indigenized Europeans who then went on to colonize on other continents, bearing the cross alongside the sword and the fire and the disease — would we save the world if we all became atheists, or any religion that wasn't Christianity, especially a self-styled "earth-based" religion? Well, I'm not a Christian, wasn't a Christian for very long, and am opposed to many tenets of its ideological form. I desire to reclaim the animist worldview that belonged to my ancestors before Christianity came along, and I think Christianity has a uniquely destructive history compared to other major world religions. But I also don't think any religion is good just because it's not Christianity, and atheists don't have a blank check here either. What you believe is not as important as what you actually do based on those beliefs. And in some cases, Christianity has syncretically integrated with indigenous communities' existing beliefs; I'm not going to tell them that's wrong. There's also a special history of Christian leftist activists, which I think is worth remembering, and I agree with people who say that the historical Jesus, whoever he was, probably would sympathize with a communist and/or anarchist philosophy.

So of all these possible culprits for why things on our planet feel so hopeless on both ecological and sociological levels, I can't pick anything that could easily be proven, and I can't think of anything else. I suspect the culprit may be more of a Gestalt effect from the factors already described. For several hundred years if not a couple thousand, the interplay between ill-chosen tech, capitalist machinery and morals, resource hoarding, and anti-animist mindsets have created a great dung ball that rolls along through this timeline without any beetle behind it.

For even a chance at addressing the dung ball, I've resolved myself to combat it by several means. These means are what I've sworn myself to as a witch who is also a kinkster. Rites of the seasons, of the earth, of communal sacrifice and endurance and consensual power transfer. I think other people would do just as well to choose other routes like forming unions at their workplaces; I'm no stranger to union organizing, and the reason I stopped was really for mental health, so when I say what I'm trying to do as a witch, I don't mean that my way is the only way. The dung ball can be stopped with a diversity of strategies, of which mine are only a few.

My future writings here are part of that struggle: an effort to fully kindle animist relations with nature, to imagine new rites of passage into truly local communities, to ponder and celebrate ways to heal from the trauma that the dung ball inflicts upon us, to further pare down the reasons why I ever need to set foot on social media instead of maintaining healthier online and offline connections. No matter when apocalypse inevitably comes for the Earth and any life that started here, whether that's in a century or in literal aeons, one thing that is not inevitable is how we choose to live before the end. It is only fitting that the choices we might make for better living before the end are also likely to help prolong our ecosystems' life, that we might survive long enough to leave our planet for a new one when the sun prepares to eat this place. I no longer fear the heat death of the universe itself, for even if humans could survive eternally except with that limitation, I would consider our species' achievement blessing enough.

I said I would make future newsletters shorter than my first. I may have lied, since this is even longer. But I'm hoping that some of this explosive verbiage is just the initial, thick trunk of a tree whose top sprouts a thousand smaller branches and twigs. Thank you for bearing with me on another long read, and a heavier one to boot. The next piece will expand a lot on my final words above, and may be more hopeful, or at least more invigorating.

I also won't close every newsletter with a plea for paid subscribers, but as I keep working to get this fully off the ground, I do want to note based on a test subscription that the paid tiers are apparently not 100% visible when you sign up. So please note that if you're looking to pay, after you subscribe and verify your e-mail, just click on the red circle on the bottom right of the page and this will bring up a panel with a link to your account info. Click the red button for plans and start off with the 14 day free trial for the $1/month Supporter tier, which allows you to leave comments and read most locked posts. After that period ends is when I gather you can select exactly which subscription tier you'd like.

Since this info isn't displayed to you immediately, I also want to mention what can happen if you choose a tier higher than Supporter. The Occult tier, for $5/month, unlocks extra-special posts and gives you my e-mail address to send questions which I'll answer in a seasonal Q&A entry if I receive anything. Lastly, the Alchemist tier ($20/month) means you can do all of these other things and also request full essays by me on a certain topic that I'll post within a month of you asking, subject to my discretion if I think a topic is inappropriate. Hopefully once you're a Supporter you'll be able to read this for a while and then decide whether you'd have an even better reading experience at a higher tier.

That's enough marketing for now, and I promise that once I have at least one subscriber at a higher paid tier, I won't feel like I need to reiterate this info too often, since I'll be assured people know where to find it in their account if they need.

Thank you again, and enjoy the last days of Scorpio season. I'll be sending my next missive on the capitalist holiday of Black Friday.

Member discussion