Full Moon (Zodiac Series): Underworld, Otherworld

It's Friday. Hello.

To some extent I'm grasping for what or how I can still write this week, because it has come to pass that I'm about to lose my second pregnancy, seven months or so after losing my first. I cannot say whether my grief is proving easier or harder to process than before, with so many factors at play, including that this time the pregnancy is ectopic. I do know that because of the ways in which this is indeed grotesquely difficult, it feels most tempting to write something about those challenges — and about how they connect with the first loss, and to generally revisit the ideas and sentiments underpinning my quest for a child in this terrible era. Simultaneously, two nights ago I quite suddenly overcame the greatest source of psycho-spiritual anguish that has faced me during said quest, and thus as I sit here in an odd, unprecedented serenity I feel just as tempted to elaborate on my epiphany that is showing me a path beyond fear.

But in either case, the right words — the truly right words — are not yet ready.

Fittingly, I may approach things slantwise through what I had intended to write originally. Here is the next installment of Salt for the Eclipse's "zodiac series." I have meant to serve Gemini season with some thoughts on whatever lies beyond the veil, after this life, guided by the image of Gemini's ruling planet Mercury — he who rules over many exchanges and liminalities but none so darkly powerful as the journey between this world and another.

Underworld: Land of the dead

Though Mercury is the god's planetary name and the face he wore in imperial Rome, I know the silvertongued psychopomp a little better in a Greek context, where he is Hermes. In turn, the first stories of the Underworld that I was raised with were also Greek. This shadowy land was the domain of Haides[1], joined for half the year by Persephone; it was bordered by the river Styx, guarded by the three-headed Kerberos, and divided into various smaller realms for the heroic dead, the more ordinary dead, and the dead condemned to punishment. And although this triad of deathly destinies calls to mind the later Christian division of heaven, purgatory, and hell — indeed heavily shaping those concepts through Hellenic influence in the Church's early days — all of the Underworld was equally "hellish" in the sense of being treated as something underground, subterranean, chthonic.

Chthonic afterlives are by no means confined to Greco-Roman cosmology, either. They abound in other animist systems of the past and present, whether as all-inclusive homes for the dead or as fates reserved for only specific dead. The Mesopotamian civilizations had Irkalla; ancient Egypt had Duat, which must be traveled before one's heart could be weighed and judged; the Aztecs and their descendants have known the Mictlan; the exact placement of the Nordic tradition's Hel (or Niflheimr) is a matter of interpretation but it at least lies somewhere beneath the roots of Yggdrasil and thus presumably beneath Midgard, where living people dwell. These are a scant few examples out of hundreds, if not thousands. And I will admit that because my own sense of death centers around its finality and the dissolution of flesh, even when I was an atheist I responded intuitively to chthonic afterlives more than to the notion of heaven. Especially if that Underworld was morally neutral, swallowing the righteous and the despicable alike.

However, relating most easily to a chthonic Underworld does not preclude apprehending its celestial twin. As the esoteric scholar knows: as above, so below. What is below does not have to be seen as separate from what is above. Not only are the stars are our ancestors, and not only does the night sky tell a story of things echoed from the deep past; the sky may indeed mirror the subterranean directly. Any of us could live "above" the sky if culturally our linguistic schema were that gravity makes us fall "up." Perhaps so many lakes are sacred in so many places because when their water is clear and smooth it reflects the heavens as though there were also a galaxy inside the earth's bowels.

This is also why something resonated within me when I read one view of indigenous Australian afterlives[2] presented in Tyson Yunkaporta's Sand Talk. There he describes the body not having one spirit but four. The first is like a higher self that travels skyward upon death and lives among the stars; the second is bound to one's land and will remain there after death instead; the third is one's life force and flows out at the end to travel the earth as water. And the last is a shadow, that which motivates one to pursue one's desires, which sometimes makes it destructive but sometimes not. Yunkaporta does not describe the shadow spirit's fate after death, and in any case I do not feel eligible to adopt this exact ontology of the soul; but because the self is already an illusion, a limited way of understanding consciousness, I suspect that it can broadly be valuable to conceive of multiple spirits or souls inhabiting bodies during life and then dispersing in many directions afterward. Below us, above us, and all around.

But before I can explain what fully drives me to see things that way, let me turn from Underworld to Otherworld.

Otherworld: Land of the fey

I have primarily encountered the term Otherworld as an anglophone "translation" of overlapping concepts in pan-Celtic folklore. More literal translations would be something like the Un-Earth (from the Cymric Annwn) or the Land of the Young (from the Irish Tír na nÓg), or a shared concept like the Isle of Apples, which appears as a literary motif in British and Irish myths alike.[3] Although I'm fond of this last phrase for reasons I'll come back to later, I am even fonder of thinking of the Otherworld as the Un-Earth because of the etymology behind Annwn, namely the Gaulish word antumnos which would literally be the word for earth with a negating prefix. Ironically, I have yet to uncover when English adopted Otherworld as the chosen rendering, but since it does come close to something like an Un-Earth I find it suitable.

In any case, the Otherworld or Un-Earth is defined by its opposition to our own, while remaining very abstract. Different Celtic legends offer substantially different pictures of what the Otherworld contains, apart from the fact that it's a realm inhabited by supernatural beings of some flavor. They may be the Fair Folk or the Aos Sí; they may be gods and impossible heroes; they may be kings and queens that are harder to distinguish from mortal beings but clearly do not lead an ordinary existence. As a collective, I think of them as the fey. And besides having these unusual denizens, the Otherworld is also a place where time does not work the same way that it does in mundane reality; to enter the Otherworld, someone must also typically enter an unusual geographic portal, such as a cave, a body of water, a bank of mist, or sailing endlessly toward the horizon.

Some non-Celtic traditions do not describe a totally similar realm, but there are still some parallels that at least span northern Europe[4]. Nordic tradition establishes multiple worlds beyond Midgard, not just Hel, and one that very strongly suggests Annwn or Tír na nÓg is the world known as Álfheimr; this is the abode of the elves, in some stories ruled over by the god Freyr. In English, we also have the land of Fairy and its identically named residents, and the lore of these fairies has plainly formed through the merging of pre-colonial Celtic and imported pagan English stories, then through distillation in the fabric of cultural Christianity.

These are the geographic limits of any Otherworlds that I know much about, but even lacking a wider scope — which there may well be — this particular folklore thus emerges plentifully in the Celtic and Germanic aspects of my rites. And I find that in modern anglophone literature the motif of an Otherworld also has been repeatedly reinvented, often for child audiences but with an enduring appeal to adults whose nerves are tapped by some ancestral memory. There are Lewis Carroll's Wonderland and Looking-Glass World respectively, and there's L. Frank Baum's Oz, and J. M. Barrie's Never Never Land. These aren't simply fantasy landscapes like J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth, much as I admire that project; they are specifically established as otherwise impossible spaces accessible from this reality by peculiar methods. Follow a white rabbit down a hole, climb through a mirror, get swept away by a tornado, or aim "second [star] to the right and straight on till morning,"[5] the last of which implies chasing the eastern horizon — and indeed, Never Never Land always seems to be reached at sunrise. Considering the transit methods to the Otherworld already described above, I do not think the similarities are coincidental, even if they may not be conscious.

In my case, of course, I have once visited a parallel reality that I also typically refer to as the Otherworld, and I managed this through the assistance of psilocybin. Another old tale about how to enter the Otherworld — often by mistake — is to step in a ring of mushrooms, and as far as I'm concerned a hallucinogenic mushroom is a teaching vessel for fey of the woods to occupy. I've already written about that experience several times, and whether or not I ever repeat it[6] I've found the one instance transformative on levels I'm still uncovering. The most harrowing aspect was that during the "comedown" phase I was confronted by a primordial fear of death, almost as if I underwent the act of dying for several minutes. And that brings me back around to the Underworld.

One & the same

Despite everything I've written in this post so far, until now I have obscured the most important part: the recursive interplay between Underworld and Otherworld together. They are really two ways of looking at the same realm.

Where the Underworld is concerned, it may be "below" but in many mythologies it is equally "beyond." Indeed, in the Greek tradition Haides is a chthonic space beneath our feet and a strange realm beyond the borders of the world's encircling ocean. And likewise, at least the Celtic Otherworld can be both "beyond" and "below," since accessing it through a cave or a lake is a decidedly subterranean maneuver; and the etymology of Annwn may not simply be the Un-Earth but also derived from an older Gallo-Brittonic word, andedubnos, which would itself be Beneath-the-Earth. And if an Underworld is populated chiefly by the dead, it is not also without strange spirits and monsters; if an Otherworld is populated chiefly by the fey, it also often seems to be an afterlife destination for mortal souls to enter.

Typically as the Wheel of the Year turns I will distinguish between the two poles of time when the veil between worlds is thinnest. Between Calan Gaeaf and Jól, I speak more of the Underworld bleeding through, with my ritual responsibility being to welcome ancestral ghosts. Between Calan Mai and Litha, I speak more of the Otherworld intruding, and I engage more deliberately with the fey. But in the end, this is just a weighted emphasis, not an ontological division. Whenever the veil thins, this is a matter of both magic and death together.

One Cymric legend embodies this quality for me like no other, along with the sense of the Under/Otherworld as existing across multiple dimensions. This is the Preiddeu Annwn from the Book of Taliesin, and it's generally understood to be a short poem about King Arthur venturing into the Otherworld in order to recover the Cauldron of Rebirth. Much scholarship around this poem tends to focus on connecting it with later Holy Grail tales in the Arthurian corpus, since this far more pagan iteration predates all of those. However, fascinating as that study is in its own right, when reading the Preiddeu Annwn I am separately struck by how no stanza specifically names the Otherworld and instead uses various names like Caer Vandwy, Caer Sidi, or Caer Wydyr.

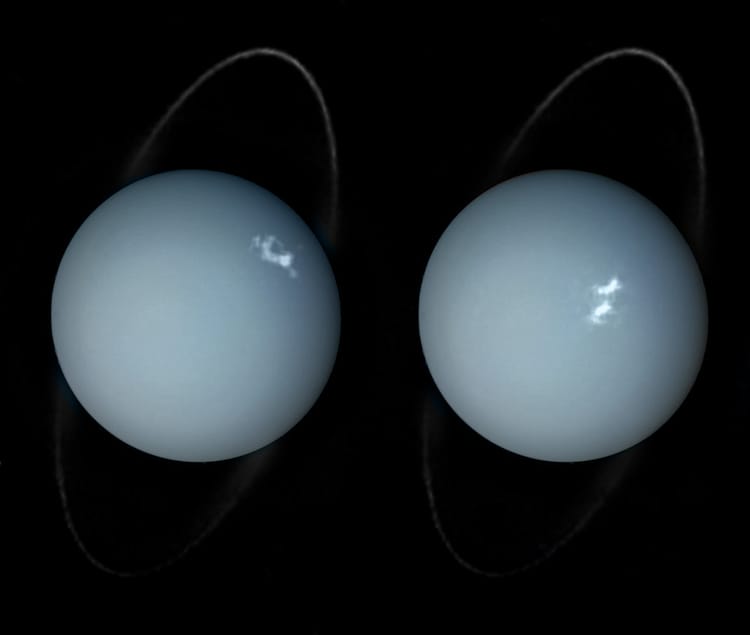

Caer is Cymric for a fortress and typically forms the first part of how many real Cymric castles are identified. As the poem continuously repeats the image of the travelers entering and exiting this fortress — noting that only seven manage to leave it at all — such a large, stony enclosure suggests a cavern, chthonic again. Yet beyond this, a name like Caer Sidi can be translated as roughly the "revolving" fortress, and a common interpretation these days seems to be that a revolving enclosure brings to mind the heavenly spheres, more precisely the rotating zodiac constellations. Arthur and his knights may at once travel beneath the earth and into the firmament. But look even further, and one may notice how Caer Wydyr is the "glass" fortress, implying a transparent structure. Without being able to see the walls, Caer Wydyr might be around us at all times. Thus the quest for the Cauldron of Rebirth seems to happen in a realm that exists below this world, above it, and all around.

Doppelgängers & psychopomps

The interrelatedness of Underworld and Otherworld would certainly explain why someone does not necessarily have to be dead in order to enter it, and why someone can still leave if they're lucky or follow the right instructions. Besides King Arthur or modern travelers like Alice, Dorothy, and the Darling children, there are other classic myths like the descent of Orpheus to try (and fail at) rescuing his beloved Eurydike from Haides' dominion. There is also a similar yet perhaps even darker Mesopotamian myth where the Sumerian goddess Inanna (Ishtar, in her Akkadian form) enters the Underworld to overthrow her sister Ereshkigal and suffers almost Christlike torments before deliverance, only to be required to have her husband take her place there.[7] Another very modern version is easily Dale Cooper's passage in and out of the Black Lodge in Twin Peaks. And I'm only naming the most immediate stories that enter my mind.

In these stories, at least, a particular and potent theme also tends to repeat, an answer to the question of whom we really meet and struggle with when one enters the Under/Otherworld: I contend this thing is one's self. It spoils only a little of Twin Peaks for me to say that Dale Cooper confronts his doppelgänger very overtly. And while in the other stories this doppelgänger is less explicitly illustrated, the principle of self-confrontation is the same. Inanna faces her sister, with the mythic motif of siblinghood being a common way to suggest twinning, mirror images. Orpheus may not see any version of himself at all, but his assigned task is to overcome his own fear of loss rather than look back at Euridike as he leads her out; as he glances back to confirm her presence at the very end, this is why he loses her forever and emerges from the Underworld alive but mad from guilt.

My own journey to the Otherworld also largely involved confronting myself from the inside out. And it was perilous, so I was wise to have a fellow human accompany me without taking the same substance. In turn, I understand more fully why gods like Hermes and Anubis are assigned the sacred function of psychopomp, soul-guide: even to undergo a one-way trip to the land of the dead, it's best to have a companion who can enter and exit that realm at will, without harm.

During the months and years to come, as I continue making sense of my multiple pregnancy losses, I am certain I will have to engage with Hermes/Mercury more often than my god has shown that face in times gone by. I have already been left with the sense that the children I began to carry and then had to give back to the Under/Otherworld will be waiting for me when I begin walking that road myself, holding my hands with their own shadowy little fingers. And also, I suppose, the planet Mercury is wrapped up in both their identities. The first child I lost would have been born in June, right at the cusp of Gemini and Cancer. And now this other loss will likely complete itself at the same time.

[1] This name (more commonly romanized as "Hades") was also the word for the Underworld itself, not just its ruling god.

[2] I emphasize one view because not only is it just one man's framing, it is also informed by his specific tribal context, and as there are several hundred different Aboriginal tribes these cosmologies of course vary wildly across that landscape.

[3] In the British context, this is Avalon, from the same root for the modern Cymric afal, "apple."

[4] And probably further, but I'm less familiar.

[5] The star addition was Disney's.

[6] I was considering it for the solstice, but my health situation now prohibits it.

[7] This sentence is then commuted in a very Persephonian way, as Inanna's husband is permitted to leave the Underworld for half the year and be replaced by his own grieving sister.

Thank you for reading. Although this month has grown difficult for me, I would like to repeat my assurance that today I'm faring much better than a few days ago. Also, while I would still appreciate paid subscriptions in this stretch of unemployment, there have been some positive developments toward the likelihood of me realigning my non-writing career (to the extent that I might even become proud of it), and under those circumstances I've managed to probably secure some better cash flow for the time being.

Next week, my offering for (and directly on!) Litha will be a midsummer's meditation on water scarcity in the eco crisis. After that, I will have a post for paid subscribers only that finally details my complete views on the ethical use of animals in both ritual and mundane life.

Member discussion