Full Moon: Winter constellations

It's Friday, and these woodlands are seeing their second day of thaw after several weeks of snow that doesn't melt, rain that always turns to ice, and bitter Arctic winds. Given that the temperatures are even unseasonably mild — we can no longer have a winter that is ever just frigid — it would be easy to mistake the energy of today as belonging to February, to spring approaching. But exact temperature aside, it's long been normal here for January to slip above freezing at times. And the current forecast is another plunge next week. And the nights may be shortening, but they are still very long.

Winter is far from over. Hello.

I have less time to write today than I normally do, due to nothing other than a scheduling hiccup. However, what I had in mind this week was relatively compact, or can be. So without further ado: today I come back to some astrolomy after a little while without. (If you need a reminder of why I coined astrolomy instead of saying either astrology or astronomy, look at the first couple of paragraphs here.)

In another context, I've started to actually teach some amateur star-finding and celestial navigation skills, so to celebrate the long darkness of the midwinter period I feel even more comfortable bringing some of that knowledge to this newsletter and framing it in an educational manner. And thus I am going to share with you how to find certain constellations in the Northern Hemisphere's winter sky, mingled with stories I know about some of these. Portions of this post will at times rehash material in older astrolomy posts, but I hope to present this material in a more pragmatic manner than before.

A quick general primer on the stars: what does "winter sky" mean?

Why do we only see certain constellations during particular times of night, or during particular seasons? Depending on how much astronomy and/or astrology you've ever paid attention to before, even this question might be novel; you may have assumed that we see all the stars in the sky every night, rising and setting every night, always found in the same position every night. But this could not be further from the truth.

To learn identification of any stars or constellations such that you can find them on a given night, it's not enough to study a star map. First, you must account for the fact that many stars are only visible in either the Northern or the Southern Hemisphere, and for stars that are visible in both they will usually only be visible (or achieve maximum visibility) during that hemisphere's summer, based on the Earth's axial tilt. Building on this fact, talking about the "winter sky" refers partly to what stars are visible in the night sky when one's hemisphere is tilted in its winter direction, e.g. further north in the Northern Hemisphere.

Secondly, you must account for the fact that whatever stars the Sun appears near in relation to the Earth, at least below a certain nightly altitude, we will of course not see those stars because they will have risen and set in tandem with the Sun, whose light obscures them completely. As the Earth orbits the Sun over the course of 365 days (approximately), this relative positioning slowly changes and the obscured stars thus also slowly change. So talking about the winter sky then incorporates this other aspect.

I will not catalogue every winter constellation of the Northern Hemisphere here today, particularly since depending on one's latitude there are "borderline" southerly constellations visible to some of us here that are not visible to others. And indeed, even of the few constellations I've selected here, a couple are fully invisible or only half-visible past a certain threshold within the Arctic Circle. However, based on my known readership, I think nearly every one of you should be able to find all of these stars in theory.

One last thing to note here: as for finding those stars, it helps a great deal to start by orienting oneself to how stars "move" relative to the Earth.[1] Because of the direction the Earth spins, if a star rises then you will see it growing higher in the eastern sky, then when it sets you will see it growing lower in the western sky. The time that any given star rises each night will generally advance by four minutes from one night to the next, meaning the star will rise earlier and earlier. In this hemisphere, if you face south then you can watch most of that night's visible stars pass left to right either ahead of you or squarely over you, at least if you have the patience to watch for hours. Meanwhile, if you face north then you will see some stars that neither rise nor set, but just spin in a counterclockwise circle, pivoting around the North Star.[2]

After you've internalized this information, which may take some nights of practice, patience, and learning where the cardinal directions even are if you are not yet sufficiently grounded in your landscape — then it will become easier to find the following constellations in the winter sky.

Finding Ursa Major & Orion

For most of this post, I will be usually using constellations' and stars' scientific names, which like the 88 scientifically delineated constellations themselves are a modern hodgepodge pulled from Babylonian, Greek, Islamic, and other ancient astronomy, plus recent Euro-colonial additions. Given that this does not perfectly correspond with all past or present cultures' stories of the stars, I want to emphasize that I am only using these names and constellation groupings for convenience, aided by my personal biases as someone descended from cultures who traditionally recognized similar constellations even if specific names and stories varied. Some of those other names and stories will appear as needed.

Now, having said that, the first constellation I will explain how to find is Ursa Major, the Great Bear. For most people on Turtle Island who experience this continent's typical and unfortunate amount of light pollution, it is unlikely that you will usually see the entirety of Ursa Major; some of the stars here are too dim. What you can probably see instead is an asterism (smaller[3] star formation) within Ursa Major, known as the Big Dipper. You probably know what the Big Dipper looks like:

The question is whether you know where it's located. The simple answer: it's always somewhere to your north, because it's one of the constellations that just endlessly pivots around the North Star.

The more complex answer: given the Big Dipper's location, even though you can always find it somewhere you may have to crane your neck more depending on the season and what time of night you're looking. I have found that winter is, however, the best time to see the Big Dipper right after the stars come out at dusk, because it hangs very low on the northern horizon before it turns slowly upward through the rest of the night. (By sunrise, it's just past fully "inverting" itself much higher overhead.) Thus these stars form a staple of winter evenings.

Note that while I have said the Big Dipper here, in English as it's spoken on the islands of Britain and Ireland this constellation is often called the Plough. In my ancestors' mythology it was the plough pushed by the first farmer to harness oxen, although they did also recognize the larger Bear constellations. This farmer is usually known as Hu Gadarn, and he maps to the modern constellation Boötes nearby, but I just call him in turn the Ploughman, working the sky's "agricultural" region.

Turning south, there is another very prominent winter constellation you can also observe without too many light pollution problems. This is Orion, who is one of my favorites. I love Orion for several reasons:

- As the Hunter in some of my own ancestral mythology, within that context he is associated with the Wild Hunt and thus I treat him as the king of the Otherworld (Arawn), the king of winter (the Holly King), and even as a psychopomp (Gwyn ap Nudd), all several faces of my god.

- In Greek mythology, Orion presents a cautionary tale about pride; though the greatest hunter ever known, he became boastful that he could kill anything, so the gods sent him a little scorpion to fight. The scorpion was agile enough to evade all of his weapons, and she killed him with her deadly sting. Then the gods hung both Orion and the scorpion in the night sky as a reminder about humility.

- Because Orion and the eponymous Scorpio have their heyday over the southern horizon at basically opposite times of year, just as Orion's reign helps to indicate the dark half of the year Scorpio's reign thus helps to indicate the light half. The pair chase each other around and around for eternity.

- The Hunter contrasts with the Ploughman on the other side of the sky.

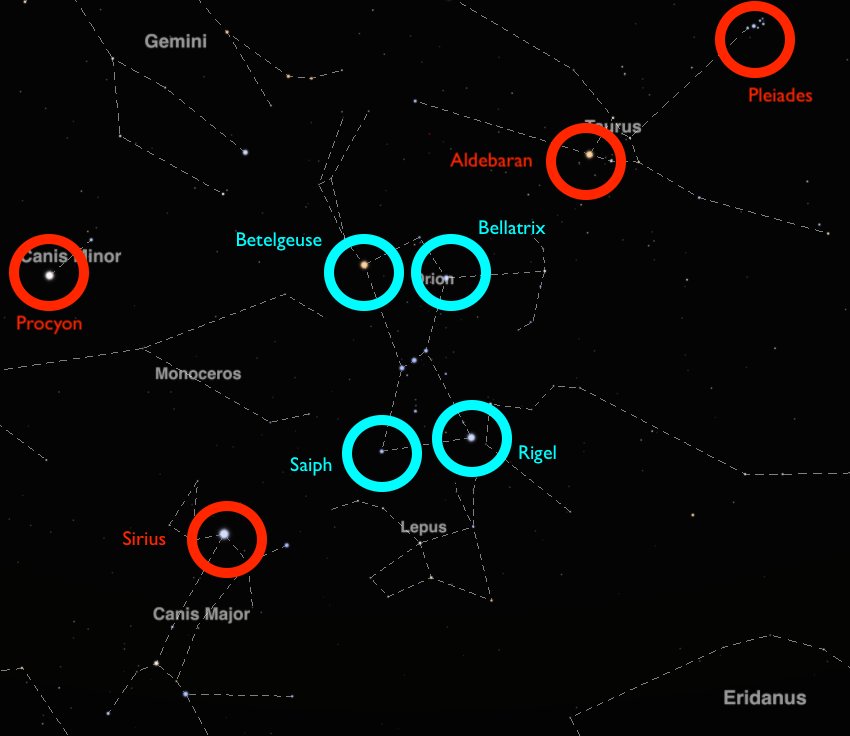

Now, technically some portions of Orion are harder to see than others, but you should at least be able to see this classic "lower" portion:

The top left star there, appearing in a warmer hue than the rest, is Betelgeuse, whose name comes from the Arabic يد الجوزاء (Yad al-Jawzā’, "hand of Gemini," which will make more sense in the next section). Betelgeuse, a red giant star, is generally regarded as Orion's shoulder. The top right star is Bellatrix (from Latin), his other shoulder; the bottom left star is Saiph (from Arabic), his knee; and the bottom right star is Rigel (from Arabic,) his opposite foot[4] as Orion is seen as kneeling. The three stars cutting through the middle form Orion's belt, and if you have slightly better visibility you can also see his short sword dangling from it as another couple of stars.

Orion is considered to belong to the Northern Hemisphere's stars, given that he can be seen in whole or in part all the way up to the North Pole. But because of his position relative to the Sun, we can see him best during winter regardless. While his visibility is slowly diminishing by this point in January, he is still overhead nearly all night. So on some evening this month, look east to catch him climbing higher, and if the night has further advanced you can see him walking some distance above the southern horizon.

Using Ursa Major & Orion to find other constellations

The value of learning how to find Ursa Major or Orion is that knowing where either one is located will help you find several stars that are both worth finding in their own right and also highlight other constellations.

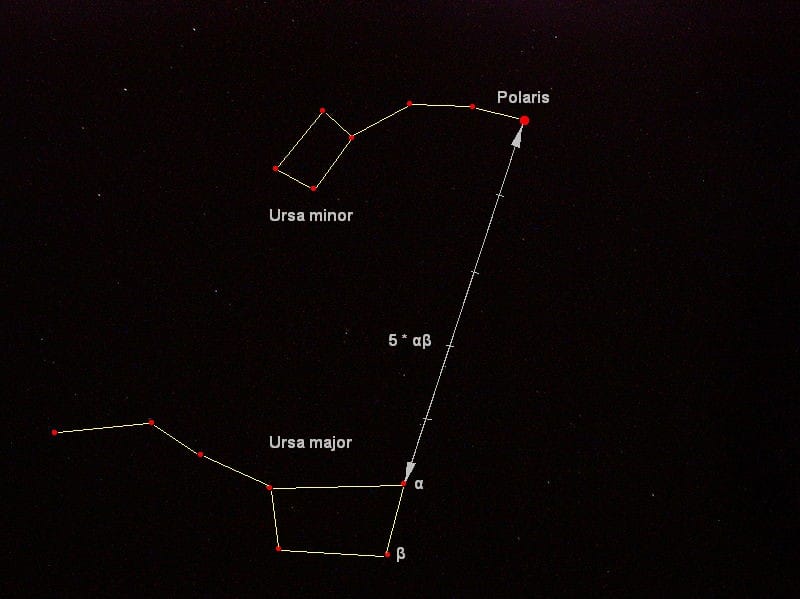

As you may or may not have heard, Ursa Major — or at least the Big Dipper portion thereof — can guide you to finding Polaris, the North Star. Polaris sits on the tip of the handle of the so-called "Little Dipper," an entertainingly similar asterism in the constellation Ursa Minor; but with average light pollution Polaris can be somewhat dim, and the rest of the Little Dipper is too inscrutable to be of much use. Thus, the rather-visible Big Dipper comes to the rescue, especially when it's right on the north horizon during a winter evening.

As illustrated below, two stars in the Big Dipper, commonly known as Dubhe and Merak but also classified as Alpha Ursae Majoris and Beta Ursae Majoris (hence the Greek lettering), are nicknamed "pointer stars" because if you imagine a line drawn between them that also extends past Dubhe, this line would intercept Polaris.

On a clear enough night, feel free to give this a try sometime. If you can find Polaris you may eventually not even need something like a compass to help you know where north is at night, which is an invaluable survival skill and likewise an important means of orienting oneself to the landscape and the cosmos all at once.

As for Orion, three of his brightest stars also serve as reference points for others, as I've illustrated myself from a simulation screencapture:

Betelgeuse points left to Procyon, the brightest star in Canis Minor. Saiph points left and down to Sirius, the brightest star in Canis Major — and the brightest star in the entire night sky. Various stories are associated with both the Little Dog and the Big Dog, but in my personal cosmology they echo Orion's place as the Wild Hunt's leader; they are the Cŵn Annwn, magical hounds of the Otherworld.

Meanwhile, Bellatrix points right and up to Aldebaran, the brightest star in Taurus the Bull, and then in a fairly straight line we can also use these two stars to find the Pleiades star cluster, which will look more like a blur because of how many stars are in it. Many cultures including my own ancestors' call the Pleiades "the Seven Sisters," who are often being chased by the bull behind them, or by Orion; but they also generally escape in these stories.

While there are certainly plenty of stars that exist in the negative space of this image without being depicted, it's very unlikely that you will see them unless you live in or visit a dark sky sanctuary. So this reference technique works quite reliably as long as you can see Orion's basic shape, especially because the other stars in question are either as bright as or brighter than his own stars.

And do you remember me mentioning Gemini earlier? As you can see in this image, Gemini is situated next to these constellations, on the upper left. While no specific "pointer stars" indicate any stars within Gemini, once you can infer the locations of Canis Minor and Taurus, it becomes fairly simple to deduce where Gemini is, and (though not caught in this image) the Twins' heads may be spotted as the two stars Castor and Pollux. This positioning explains why Betelgeuse's Arabic name refers to "the hand of Gemini"; Gemini seems to sit atop Orion's shoulder in this way.

While there are a few other bright constellations in the winter sky of the Northern Hemisphere besides these ones, if you can identify this collection with Orion at the center, then you are off to an excellent start. And furthermore, by identifying Taurus and Gemini you can start to use them as references for other zodiac constellations that stretch to either side of them along the plane of the ecliptic.

I hope this was edifying, and I hope that if the stars have interested you for a while but still gone unstudied, perhaps this may encourage you to build more of a relationship with them.

[1] That is, we are simply under the impression that they move because the Earth itself is spinning and we are thus constantly looking in a new direction overhead. But it's fair to say there's at least "apparent" movement.

[2] I believe I have no readers in the Southern Hemisphere, but if you ever travel there — and I would love to for exactly this reason — then you will need to turn north in order to watch the grand procession of constellations from east to west, which from this perspective means they move right to left. And in turn, you will need to turn south in order to watch any constellations spin around, and in this case they will spin clockwise; there is currently no South Star for them to pivot around, either. And of course, any constellations you see in the Southern Hemisphere that you can also see in the Northern Hemisphere... will appear "upside down."

[3] An asterism can also be a formation of bright stars that otherwise belong to multiple constellations, such as the Summer Triangle, which is composed of Vega (in Lyra), Altair (in Aquila), and Deneb (in Cygnus).

[4] The Arabic derivations here are respectively سیف الجبّار and رجل الجبار, Saif al-Jabbar and Rijl al-Jabbar. The former refers to "the saif of the giant," and a saif is a type of sword, so evidently Islamic Golden Age astronomers saw this as where Orion's sword hung. But the latter does refer to "the foot of the giant," so there has been less evolution on this front.

Thank you for reading. It's been a little while since I bothered to ask, but if you enjoyed something about this post, especially if you've been reading for free for a while, I would like to once more request that you consider upgrading to a paid subscription. There are two reasons for this: 1) I've been unemployed for nearly 12 solid months and am still searching for full-time work, and 2) all writing is chronically undervalued in this society, especially with the advent of LLM usage.

Even if you aren't capable of paying, however, I still do appreciate your readership and the opportunity to be in dialogue together. Thank you again. Next week I'll have a post for paid subscribers on my mental health as visualized through the metaphor of my Capricorn Moon; after that, I'm going to examine the mystery of who really holds power in D/s (consensual power exchange) relationships.

Member discussion