Full Moon: Children of Llŷr, children of Dôn

Hello. It's Friday, and I've been free of my local air quality alert for about 24 hours. I hope that if you've been facing smoke this week as well, it's starting to clear up too. This has been a harrowing time, and I'll admit that while I hadn't thought the smoke was bad enough in my area to bypass my home's air filter, some signs are pointing to the fact that it did, and likewise for my owner. Luckily the effects are only mild to moderate, but like most people on this part of occupied Turtle Island, I'm not used to coping with wildfires. I have many pained, angry feelings.

But I'm going to try and keep them to myself for now, working through them in private until I see how the rest of the summer goes. Here during the Full Moon, in the spirit of my recent resolution to connect more with the animist side of my practices, the thoughts I have an easier time voicing today are about Cymric folklore — or in my opinion, mythology. Many scholars insist on drawing a line between those two concepts; folklore is culturally specific but independent from any religious beliefs, whereas mythology comprises stories considered by their tellers to carry a sacred quality. I think this division makes sense outside of animist societies, but in an animist framework the sacred can appear anywhere. Furthermore, even outside of my own non-expert academic opinion, I believe based on my own upbringing that Cymru — as a reminder, Wales — does preserve a few myths ultimately belonging to a non-Christian, animist worldview, even if the full cosmology and rituals related to that worldview are perhaps permanently obscured.

Two thousand years of colonization (or: two thousand years of syncretism)

I am a witch with interest in reconstruction of "British paganism," but unlike a fair amount of other people who would describe themselves the same way — particularly those on Wiccan or Traditional Witchcraft paths, though I harbor great respect for them — I don't posit a concrete link between what we practice today and what my ancestors would have done. That is not to say I see no throughline from the past to the present; people on the island of Britain have never stopped developing animist and/or magical traditions over the last two millennia.[1] However, I see no well-substantiated grounds for assuming that anyone, even a practitioner of a familially inherited tradition, is following rites that exactly mirror those of, say, the Druids; religion, especially animist religion, evolves too fluidly to remain so static. I also see no well-substantiated grounds for assuming that any modern British-aligned practice has descended with zero interruptions over the centuries from an original Iron Age Celtic form. This is not like the constant persistence of Shinto animism in Japan, nor the dwindling but closely guarded animist traditions of modern, threatened indigenous communities. Interruption has happened, and it can't be reversed.

I can think of at least five consecutive reasons why any Cymric animist heritage practice faces this unavoidable problem.

- There are no written records about religion by British Celts themselves. The Celtic language spoken across Britain in the Iron Age through Roman occupation was Common Brittonic. But while far fewer Romanized Britons actually learned Latin than is sometimes imagined, Latin was necessary for writing as Common Brittonic had no writing system. There are a few scant examples of Ogham lettering being transferred from Old Irish to Common Brittonic in some regions of Cymru, but we basically do not see any British Celtic language written down until the post-Roman period as Old Welsh arises.

- Most of what we do know about British Celtic religion is thus only within the context of Roman occupation, as Celtic deities were syncretized with Roman ones. The colonizing Romans were god eaters and myth stealers, appropriators par excellence. Nowadays, barring some fantastic archaeological discovery, it's impossible to untangle what Britons practiced right before Rome invaded from what they practiced under Roman subjugation. Irish mythology has overall survived a bit better, but we still don't really know all the parts that are uniquely Gaelic vs. which come from an older substrate that influenced the British Celts as well. And of course, the fragments of documentation Romans actually wrote about the Britons before conquering them were unverifiable — such as the wicker man sacrifices, which might have been a propaganda invention — or focused on the conquest itself. The Romans burnt the sacred groves on Ynys Môn (Anglesey); what we know about those groves now is only that they were sacred enough for the Romans to erase them.

- Christian syncretism has continued the Romans' colonial legacy. As I've said several times in other posts, I don't see the Christianization of Britain as an all-encompassing death knell for indigeneity and animism; ultimately I blame capitalism and industrialization much more. However, I also won't downplay the problems caused by Christian ideological insistence on overcoming the pagan past. No matter what pieces of lingering British Celtic animism have been practiced ever since the medieval period by laypersons who either deliberately or unthinkingly blended those older traditions with Christianity — the Catholic Church and its Protestant successors in Britain have either scorned documenting what pagans are up to, or have only documented them through a Christian lens that only further muddies the waters of what is distinctly Celtic vs. a Roman imposition.

- Saxon, Viking, Norman, and even Gaelic colonization swallowed or sidelined all Celts on the island of Britain. Debates rage as to whether the Saxons (and Angles and Jutes) established England through a direct ethnic cleansing pattern or through something more like death by a thousand cuts; I think the evidence better shows the latter, in the sense of constant Saxon settlement expansion paired with raids and anglicization of enslaved Briton captives. Regardless, that may well sound familiar to students of more recent colonial history. The establishment of the Danelaw also marginalized Saxons themselves where Nordic settlement had occurred, but this didn't improve the position of any remaining Britons there whose kingdoms were already destroyed. Increasing Scottish-Gaelic settlement of the far northern highlands also completed the dispossession of any lingering British Celts-as-Picts[2]. And lastly, Norman imperialism under the likes of Edward Longshanks cemented Cymru as a tributary nation whose cultural artifacts were the English crown's right to harvest, right down to the title "Prince of Wales."

- The Cymry (that is, the Welsh, Cymru's people) reached industrialization and whitening, as discussed repeatedly in older posts. Any desire to remain connected to uniquely British Celtic animism, no matter what had survived from the Iron Age, was placed under stress as indigeneity itself was disrupted and "Welshness" was homogenized with anglo-dominant whiteness, aligned with the economic and military programs of the "British" Empire. This didn't always happen willingly in Cymru itself (see the reaction to the English occupying government's commitment to Cymric language eradication); Cymru has always taken the shit end of the bargain as it's become Britain's equivalent of West Virginia. But speaking of West Virginia, Cymric people often began to understand their best chance at survival was to embody whiteness elsewhere in the world.[3]

With so many colonial incursions, one of the most glaring envelopments that's happened in the realm of distinctively Cymric culture is probably what's become of the legends of King Arthur. Arthur could have been anything from a real individual who fought Saxon raids, to a messianic figure invented as a morale booster during those raids, to a much older mythological figure — that is, a sacred figure — repurposed into that savior function. I have my own personal hypothesis about how a "real" Arthur might have fit into late 400s to early 500s Britain, but I think it's interesting to consider his ancient mythological potential insofar as some of the oldest, explicitly Cymric legends about him extend to cosmological assertions of the Otherworld, or to side characters such as giants that are transparently Titan-like mythic beings surviving within wider surveys of Celtic folklore.

Unfortunately, the Normans and the wider medieval francophone world became obsessed for a few centuries with essentially writing fan fiction around this hero and his retinue, working from their own hegemonic position in relation to the Cymry. The Frenchified, more-substantially Christianized Arthurian works are a compellingly written but nakedly obvious act of cultural exploitation. Cymry today are quick to insist upon Arthur's "Welshness" not out of much-stereotyped pridefulness about our scraps of overrated culture — but rather because the colonized Arthur has become the better known form, and this remains a wound to Cymric identity.

However, despite this particular example, and despite the factors I listed above that led to it, I also think it would be inaccurate to describe the thread between Iron Age Britain and modern Cymric animism as being so interrupted that it's wholly severed. Due to the many syncretic blendings that have taken place, it's less like the thread has been cut at several points, and more like the thread has passed behind a fabric we can't turn over. I doubt that anyone today can successfully find that which is hidden, whether by directly uncovering what's missing or by proposing an accurate model of what ought to be missing.

We will never know what came before, and I think anyone claiming otherwise is wrong; at the same time, though, pieces have survived without our precise knowledge of what or where they lie. Discernment and personal interpretation about what those pieces might be falls to we who seek, we who wonder, we who hope to reconnect. And in my case, I'm someone who increasingly looks to one body of Cymric literature that's been colonized by Christian influence but has always retained a completely, un-appropriated Cymric character, never overtaken by external interpretations. These stories resonate so strongly in my psyche that in them I see a clear sacredness suggesting myths that have survived. They are also certainly literary works in their own rights, full of embellishments, but this makes them no different than what the Eddas have taught us about Nordic mythology.

I am talking, of course, about the Mabinogion, alternately phrased as the Four Branches of the Mabinogi.

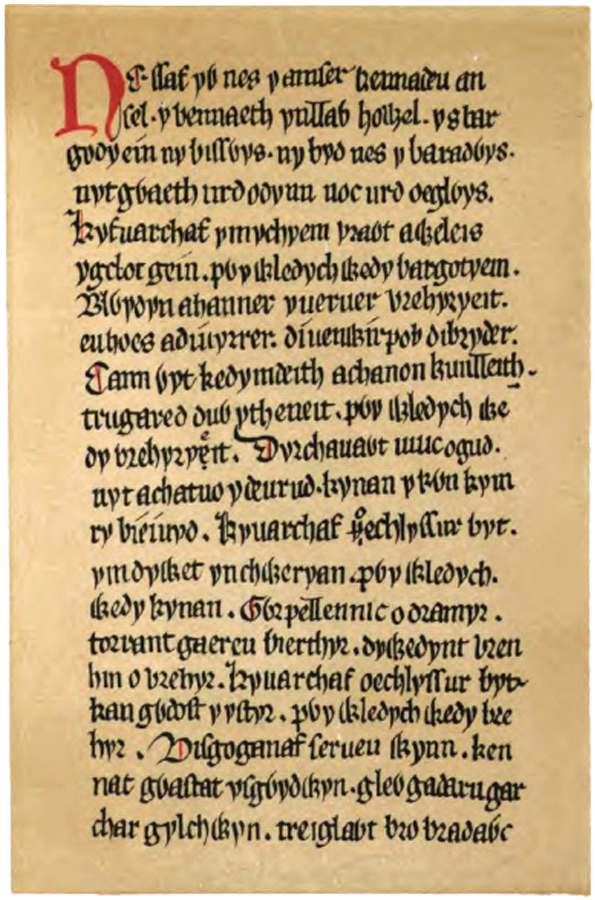

Probably no one will ever know whether there are just four branches, or what a deliberate choice of four would signify. Nobody even agrees on the etymology of Mabinogi. And while one author likely devised the four stories in their recognized forms found in the White Book of Rhydderch (c. 1350) and the Red Book of Hergest (c. 1382-1410), pieces of earlier versions can be found going back to the 1200s — and crucially, the scholarly consensus is that these are compilations or iterations of even older material. How old? Once again, no one can agree.

I personally think that certain elements of the stories must at least pre-date Christianity in Britain, with a few characters possessing divine qualities — and with some storylines echoing Irish myth, which to me suggests a common body of animist lore dating at least to the point at which Brythonic Celtic languages (Cymric, Cornish, Breton) and Gaelic languages (Irish, Scottish, Manx) diverged, and that falls before Roman occupation of Britain. The only question of age in my own mind is whether these stories were imported from mainland Celts when the indigenous Britons were Celticized, whether the stories developed in Iron Age Britain after that point, or (improbably) the stories are tens of thousands of years old.[4]

Whatever the case, here are some meditations I've had on the pre-Christian animist characteristics I see in each branch of the Mabinogi. I'm not going to review the stories themselves in exhaustive detail; I'm hoping a summary will do. For anyone interested, I'm happy to write longer reviews at later dates.

I. Pwyll: Allotments

Pwyll is the Prince of Dyfed. He mistakenly kills a stag being hunted by Arawn, Lord of the Otherworld; in exchange he's bidden to switch places with Arawn and rule over that land for a year, fighting Arawn's sworn enemy at the end. Though Pwyll is tempted to have sex with Arawn's wife, he refrains; he also defeats Arawn's traditional foe. Thus Pwyll returns to Dyfed and sees that Arawn also ruled it well.

Continuing this run of wise choices and good fortune, Pwyll then sees a beautiful woman, Rhiannon, riding on a horse which it seems impossible for his own horse to catch up with until Rhiannon stops and asks to marry Pwyll. The wedding is rocky as an interloper, Gwawl, nearly manages to cheat Pwyll out of both his bride and the feast, but Rhiannon tricks Gwawl in return.

Months later, Rhiannon bears Pwyll a son who mysteriously disappears; rather than take the blame, the nursemaids say Rhiannon herself ate the boy, and Rhiannon is punished in a humiliating fashion over seven years. However, the child is not dead, only abducted, and he's rescued and raised by a kind couple, then eventually returned to Pwyll and Rhiannon. He is named Pryderi by them, meaning "loss" or "anxiety."

The first branch ends here. Within it I see three cycles of displacement and restoration. Something is out of its proper place — a living man in the land of the dead (or the fey), a horse of impossible speed followed by a disruption of a wedding, and a kidnapping — and then it is put back. The cosmic order cannot really be broken; the world course-corrects itself. Preserving balance is something to reward or at least admire.

We could see this as a Christian tale, but in this first branch a pagan cosmos is explicit. The origin of Arawn's name is unclear, yet he's undoubtedly a god, presumably of the dead if not also being the actual bringer of death.[5] He might also carry a seasonal function as he fights his foe Hafgan every year. Less definitively non-Christian but certainly intriguing is the character Rhiannon, whom some scholars fancy comparing to the continental Celtic horse goddess Epona. I find the argument there rather thin; still, I feel compelled to bring it up. In the tale of Pwyll, we find at least one pagan deity, and this casts the story's possible lessons into a more animist light — an investment in preserving the status quo, to be sure, but where the status quo is cycles of the natural world: seasons, reproduction, and children growing up.

II. Branwen: Vengeance

Branwen is the sister to Brân the Blessed, who is king of Gwynedd; both of them are children of a male entity named Llŷr. Brân gives Branwen as a wife to the king of Ireland; however, the siblings' half-brother Efnysien resents not being consulted in this, and he mutilates the Irish king's horses in retaliation. To rescue the alliance that he wanted to forge, Brân gifts the Irish king with many things, including the magical cauldron of rebirth that can resurrect any body placed within it (although they cannot speak). However, once Branwen goes to live in Ireland and bears the king a son, her husband still decides to punish her for what her half-brother did. She's treated like a prisoner, beaten, and given thankless labor.

Rather than simply submit to this treatment, Branwen catches a starling, teaches it to speak, and sends it back to her brother to tell him about her trials. And indeed, now Brân comes to Ireland with an army to avenge her. Various attempts are then made back and forth to sue for peace or sabotage it; Efnysien even kills Branwen's son, and in the war that breaks out the Irish use the cauldron of rebirth to resurrect their dead, until Efnysien breaks it by climbing in it as a living man, killing himself in its destruction. Besides his death, only seven men from Brân's army have survived, along with Branwen, and then the entire population of Ireland is dead except for five pregnant women. Brân himself has been poisoned, and he orders his own head severed for the survivors to carry and bury in London; this head speaks prophecies along the journey, and it is said that as long as the head remains buried Britain will never be truly conquered. Branwen meanwhile dies of grief.

The second branch ends here. This is another tale of displacement and return, but while the first branch's situations implied the restoration of justice, the blood feud now depicted is a quest for justice twisted to escalating revenge that culminates in genocide. It seems cautionary; and on top of the pagan motif of the magic cauldron, Christian concepts of evil are not responsible for what happens, for the main culprit is usually Efnysien, whose name means "strife."

Could Efnysien be some medievally reconfigured pagan god of discord, analogous to the Greeks' Eris? All the children of Llŷr seem potentially divine to me. Brân is described as a giant, and he doesn't appear to be mortal in a traditional sense. Branwen doesn't necessarily have divine abilities, since training a starling to speak is within mortal capacity; but her name means "white raven" and I have to wonder about some kind of avian goddess who can master all birds. And Llŷr himself, though not pictured, is understood by scholars to be a parallel of the Irish sea god Lir, father of the figure Mannanán. Not coincidentally, Llŷr's children are not limited to Brân, Branwen, and Efnysien; he too has a son named in parallel: Manawydan.

III. Manawydan: Affliction

Manawydan returns back to Cymru after the affair in Ireland. He should now be king in Gwynedd, but a usurper has taken his place. As it happens, Pwyll the king of Dyfed is also dead, and his son Pryderi is friends with Manawydan; he offers Manawydan the throne of Dyfed and hand of Rhiannon. Thus Manawydan weds Rhiannon — but the two of them, Pryderi, and Pryderi's wife suddenly find the land of Dyfed transformed to a waste where all the other people and livestock are gone.

The quartet try to survive just by hunting, but this isn't enough. They travel to England, where Manawydan and Pryderi are so skilled as craftsmen that they ought to be able to make a living there; however, instead they're resented for their talents. Eventually they give up and return to Dyfed. A couple of other strange but minor episodes occur until the final act: Manawydan tries to farm a field of grain, but what he plants is cut down repeatedly, until he discovers mice are to blame.

He catches one mouse and declares he will execute it publicly. A scholar, a priest, and a bishop each ask him not to do this; Manawydan insists, until the bishop reveals himself as the brother of Rhiannon's cheated suitor in the Mabinogi's first branch. The bishop can actually use magic, and the mouse is his transformed wife; he himself cursed Dyfed to become a wasteland. Manawydan spares the mouse's life in exchange for putting everything back how it ought to be.

The third branch ends here. This story seems the most affected by evolution over time; however old it originally is, by the time it was recorded in this format England existed, and the existence of a priest and bishop finally gives us some suggestion of Christianity. However, the bishop is hardly a positive figure, in fact correlated with the devastation of a kingdom. I'm not sure if that's a heretical metaphor, but it's at least clear that Christianity isn't what saves Dyfed. The fertility imagery is also, for lack of a better word, potent.

IV. Math: Transformation

The kingdom of Gwynedd is now ruled not by the children of Llŷr but by the children of Dôn. The king himself is Math fab Mathonwy. When not at war, he's magically protected by having his feet held by a virgin girl. His current foot-holder is named Goewin, and she is very beautiful; Math's nephew Gilfaethwy lusts for her. Gilfaethwy and his brother Gwydion, a magician, conspire to send Math off to an unnecessary war with the kingdom of Dyfed, and while Math is gone, they both rape Goewin. Pryderi is also killed, and when Math discovers what's happened to Goewin, he marries her in recompense; he also transforms both his nephews into animals. Gwydion and Gilfaethwy spend a year apiece as a hart and hind, then as a boar and a sow, and then as a wolf and a she-wolf, bearing children each time.

After this punishment, Gwydion somehow convinces Math to take Gwydion's sister, Arianrhod, as the next foot holder. However, when Math tests Arianrhod's virginity by having her step over a magical wand, Arianrhod spontaneously delivers a child who runs away to the sea. She also drops something else (rendered either as another child or as the placenta) which Gwydion saves and ultimately raises to boyhood. Arianrhod is angry when she finds out about this, and she lays a tynged (a curse, think like a geas) upon the boy that says he will never have his own name, nor be armed with weapons, unless she gives them to him. Gwydion naturally tricks her into doing both of these things.

As this named boy, now Lleu, grows to manhood, he is also cursed by his mother not to have a human wife. Thus Gwydion makes Lleu a bride out of flowers, who is named Blodeuwedd. However, Blodeuwedd is not faithful to Lleu, falling in love with a hunter who seeks to learn how to best kill Lleu so that he can have Blodeuwedd for himself. Blodeuwedd manages to find out that Lleu cannot be killed by any normal means, only through an almost impossibly engineered situation; nonetheless, this is achieved. Mortally wounded, Lleu turns into an eagle and flies away, where Gwydion recovers him. Ultimately, Lleu kills Blodeuwedd's lover, and Gwydion transforms Blodeuwedd into the first barn owl, a hated bird.

The fourth branch ends here. And in the fourth branch, all is quite different from how it went in the first. There is no justice, no proper placement of anything. Everything is liminal and transitional, presented chaotically, ambiguously, almost nihilistic at times. The line between human and animal (or even human and plant) is constantly blurred, and Lleu can be killed neither by night or day (thus at twilight) among other complex prohibitions. Gwydion is like a trickster god, sowing Loki-like chaos and only being occasionally punished for his transgressions. And if he is a god, then what if his kinfolk? What of the other children of Dôn?

The sea & the stars

I love all these stories and have cherished them for nearly as long as I can remember.

I have also largely been content not to intentionally seek deities within the Mabinogi, because they are just wonderful (and perverse) without any further explanation behind them. Even now, I remain reasonably convinced that the one god to whom I dedicate myself — known sometimes as Arawn — is only one within the potential pantheon hinted here. I'm not looking for more gods specifically to worship them.

But in turning my gaze more closely toward what I think Cymric animism ought to look like for me, I do wonder what divine forces besides Arawn there are, even if I'm not sworn in blood to their service. And if nothing else, I find myself joining in some other people who have seen potential in the figures of Llŷr and Dôn.

Llŷr is a sea god in keeping with his Irish counterpart; as for Dôn, scholarship used to supposed she was a male figure, but now the consensus is she might be female, so I suppose she is a goddess, specifically a goddess of the stars. This isn't an arbitrary assignment — in Cymric constellations, the one Greeks named Cassiopeia is "the court of Dôn," and likewise her children are assigned other astral realms, such as the castle of Gwydion in the Milky Way, and the castle of Arianrhod in Corona Borealis.

I imagine there could be other gods and goddesses besides these (and Arawn), and I do not particularly see Llŷr and Dôn as a mated pair. But it's very fitting for a Cymric animism to possess a god of the sea and a goddess of the stars. The sacredness of these spaces for the Iron Age Britons would have to be natural. The Cymric people within living history have survived immensely off of the sea's gifts; I am the child of fisherfolk and pearl divers. Other legends of ours speak of kingdoms eaten by the ocean. As for the stars: going by the hundreds of stone circles, it's well understood that the ancient Britons were astronomers, even if they never wrote their studies down.

The sea and the night sky. Two of my own favorite things. It feels right. It's not important to me that I construct a Cymric animism off of these particular stories, partially because at the end of the day there would be many gaps to fill in anyway, and partially because it's not strictly necessary for animism to have a perfect, pure throughline from the past to the present — as I said toward the beginning of this post, these things should always have room to evolve. Nonetheless, it's tales like the Mabinogi that serve as a kernel of something from a time when my ancestors were land-connected, and this is powerful inspiration for recovering that connection myself.

[1] I'm nearly done reading Ronald Hutton's The Triumph of the Moon and have already read his Pagan Britain, and I will always, always, always recommend him for this area of research.

[2] Who the Picts even were is also a gigantic debate, but having researched this to the best of my ability for years, my own view is that they were more or less related to the British Celts further south; they were just never Romanized. Their colonization process jumped straight to Christian incursions, then the Vikings and Scots did the rest.

[3] Here is an emphatic sidebar: although I believe very, very strongly that the Cymry experienced generationally traumatizing, systematic colonization following a fairly close model to more recent capitalist-era colonialism, and although I believe the Cymry were meaningfully oppressed in their own homeland up until as recently as the early 20th century (and remain second-class citizens of the UK today) — this doesn't change the fact that in the histories of the United States and Canada, Cymric settlement contributed early on to the centuries-long assault on indigenous communities on this continent. Many, many Cymric settlers were also slave owners; it is not an accident that some of the most common Black surnames in the US are habitually Anglo-Cymric names like Williams and Jones. "Welsh Americans" are not an oppressed group, and looking at the historical record we were plainly granted whiteness over here much faster than Irish migrants were. When I talk about the Cymry as victims of colonialism I'm speaking completely in terms of the Cymric experience on the island of Britain, which is where my own ancestral experience lies right up until my mother's mother or, looking on the other side of her tree, her paternal grandfather.

[4] Yes, as if things weren't complicated enough, Britain and Ireland were not settled by ethnic Celts, instead by relatives of the Basque people. These indigenous British and Irish populations probably weren't wiped out by Celts, either, but they underwent some process of adopting Celtic languages, art, and technology. This might have occurred through relatively peaceful trade, not through a coordinated invasion, so it's hard to say whether we should apply the "colonial" label that far back.

[5] Some would say the Cymric god of death is Gwyn ap Nudd, leader of the Wild Hunt, but to me he seems like a psychopomp, bringing people to the Otherworld but not directly reigning over that land. Gwyn might be to Arawn what Hermes is to Hades.

Thank you for reading, and apologies for the delay, as this post took a lot of extra thought and review of other material. Next week might be the same, as I will be discussing stages of grief in comparison to the alchemical process; after that, there will be a special post for paid readers about the upcoming holiday of Litha/Midsummer.

Member discussion