Full Moon: A stargazing update

It's Friday. Hello. As you might surmise from the title here, for the first time I've changed the subject of this week's missive to something different than what I "advertised" I would be writing about.

Previously, I'd intended to offer some thoughts about the erotics of paganism in art. However, while I'd had a rather strong sense of what I meant to describe, and while I imagined this might be of interest to readers who subscribed to get posts about kink — which I am writing about more, but still less than I thought, at least not directly — this morning I confronted myself with several problems:

- While my art history knowledge is better than the average layperson's, I don't have anywhere near the depth of study that would allow me to really do my writing idea justice. Of course I often write about things where my curiosity exceeds my actual knowledge base, but I usually then try to frame my perspective as, "Here is something I've been very interested in, here is why, here is what I know so far, and here is what I hope to find out." In this case, what I really wanted to say would have been less exploratory and more explanatory, so I would have needed to do some research to confirm or flesh out certain parts of my post.

- This specific week, I have not had the time or focus for research on that scale.

- Of all the aspects of the Full Moon that I meditate on here, art is not actually where my mind and heart are turned this month.

So rather than half-bake a post that reads more like an abstract than as the dissertation it ought to be, I'm gambling on your good will — on how readers who give me private feedback generally mention that anything I write about is interesting to them. Perhaps a surprise post from a more intuitive source is the order of the day.

I'm going to write about some things that I've observed about the night sky this month, and that I expect to observe as summer advances. Consider it a seasonal stargazing review, in the mode of my other Full Moon posts themed around "astrolomy" or "tungolcræft." I may or may not repeat this for other seasons in the future.

The dancing ancestors

From roughly the 10th through the 13th of May, a series of extreme geomagnetic storms occurred as the Sun, right at the peak of its sunspot cycle, produced solar flares that reached our planet and disrupted satellite communications, including for my phone's navigational GPS. Many of you reading may have been well aware of the storm because of living at latitudes where ordinarily the Aurora Borealis (or Aurora Australis) would not be visible, but you were advised that on those nights if you looked outside you might have a perfect chance to catch the lights. In some cases, I know you saw them. And so did I.

I had thought my sole enormous celestial event for this year would have been the total solar eclipse; but while my two eclipse experiences have both overwhelmed me far more than my two aurora viewings, it still seemed an astonishing gift to receive the aurora right above my house. Previously, I'd watched them in Iceland about six years ago. I had gone there expecting I might not see anything at all, but hoping I would see a vast, colorful light display. What really happened was that I did see them, but largely in the far distance, and I discovered what the "Northern Lights tour" guide meant by cameras capturing different frequencies than what the naked eye sees: the lights I glimpsed were slightly green, but mostly pale white, ghostly, and nothing like what I'd seen in photos or timelapse video. My owner took a few photos with our DSLR camera, and only those few shots showed an aggressively bright green hue. Taking the experience for what it was, I did marvel — and I also thought that unless I moved somewhere further north or visited Iceland at just the right time again[1], this could also be my one and only aurora viewing. Where I live right now, sometimes the aurora will allegedly be visible, but there has been such bad luck with cloud cover each time my owner and I hear the aurora forecast, it's outright comical.

Even on the night of the 10th, when we did bear witness, we had thought we wouldn't be able. There were clouds that evening, and they were supposed to continue into the next day. Possibly they would break at various points through the night, but chances were deemed low. We had resolved to peek out the windows just after 22:00, when we would normally start getting ready for bed; we tried this, noticed the sky seemed a bit light for the Moon phase we were in, but determined that because no stars were visible, there was definitely cloud cover as well as our area's standard degree of light pollution — a far better degree than when we lived in Boston, but we are still on the very, very of the East Coast Megalopolis. The poisonous glow hides at least half the stars we ought to be able to easily see.

After 23:00, ready to sleep and giving up hope, we took one more look. Incidentally, this was near magnetic midnight, the time when the Earth's northern magnetic pole was opposite from the Sun, thus when aurora activity has the highest chance of visibility. And behold, the clouds had parted in most parts of the sky, including a large gap to the north. We shut off all the lights in our house and had to use our phone cameras to confirm what our still-adjusting eyes suggested — and indeed, if we'd been more patient, we shouldn't have used our phones as the light of their screens interfered with our night vision activating properly[2] — but there, indeed, the lights were dancing.

They covered far more of the sky than I had seen in Iceland. And there were more colors. My eyes were struggling all the while, but I could still begin to distinguish green near the horizon from a reddish pink higher up. Some of the bands' and arcs' movements were very slow, gentle, thoughtful, and some of them were wildly teeming like a salmon run.

I was stunned, but because I was better prepared than the first time, I found myself able to think more actively throughout the experience. And those thoughts often came back to the question: how should I, with my practices and my ancestry and the land I'm settled on, relate to the aurora in a ritual capacity? I have long had solar eclipses woven significantly into the very fabric of my rites, but despite being fascinated by the concept of the aurora for as long as I can remember, I haven't had many stories or symbols attached to it. It's been a grand mishmash of Philip Pullman[3], Inuit lore (and indigenous lore from further south) that I would not feel it was my right to engage with, a wistfulness about how little we know about the aurora's significance to pre-modern Celtic peoples, and a mess of competing ideas about what the lights might have been to the ancient Norse.

In the last case, I truly cannot overemphasize mess. You may have been exposed to rumors that the Northern Lights were regarded by pre-Christian Scandinavians as light flashing off the Valkyries' shields, or as the Bifröst bridge showing the way to Asgard. These are both modern Romantic embellishments, which does not make them useless to believe in now, but certainly inaccurate if describing millennia-old ancestral traditions. When examining Old Norse literature, it becomes very clear that the Bifröst was seen in that time as a much more everyday but beautiful sight: a rainbow. After resolving that fact for myself, I then had to know what Vikings or their Iron Age predecessors might have actually believed about the Northern Lights instead — and the answer surprised me. Due to periodic magnetic pole drift, during the Viking Age it may have been extraordinarily uncommon to see any aurora in that part of the world.[4] This would explain why the lights are barely discussed in such literature. And it may mean there's not much point referencing the past for creating a Nordic (or broader Germanic) aurora myth anyway.

But I think I syncretized and coaxed out something from all my ancestral threads and land threads as I watched the sky two weeks past. For me, for my rites, a cross-culturally common but beautiful story feels good: the lights are dancing ancestors. They are seen in the night sky, but they are not of outer space; they move as liminal shapes at the edge of the Earth's atmosphere. They dance because they are happy; they are not an ill omen. They dance in the darkness to remind us there can be beauty in death, in transformation, in the cardinal direction where mysteries are hidden.

Heliacal settings & risings

As for other hidden things, of the stars that I've been tracking since the autumn equinox, three have just been hidden by the Sun's light this month: the Pleiades (really thousands of stars, but visible as that distinct cluster), Aldebaran (the other bright star of Taurus), and Sirius (the brightest star in our sky besides the Sun itself). When these stars disappear from view until the Sun's course along the ecliptic has moved further on, this is known as their heliacal setting. Because of their exact placement in the sky, these three stars had their heliacal settings in extremely close succession, while their heliacal risings on the eastern horizon will be more spread apart.

I am still figuring out which stories to tell about these stars — about what it means when they are resting like this — but I know that in relating them to my surroundings on the landscape, their heliacal setting this year coincided with the end of the great spring bloom, where various flowers are still growing but the predominant color of the world is now green, green, green. Looking ahead to the rest of summer, I've guessed[5] the Pleiades will have their heliacal rising close to the solstice, heralding our region's most hot, humid, and miserable weather despite how the star cluster itself feels like a staple of winter nights. Aldebaran should follow a week or so later, thus serving as a second warning. Sirius, meanwhile, will not return until mid-August, so he does not hold the foreboding "dog days of summer" association for me that he did for the Greeks; he seems like a blessing for the summer to turn to harvest.

The summer scorpion

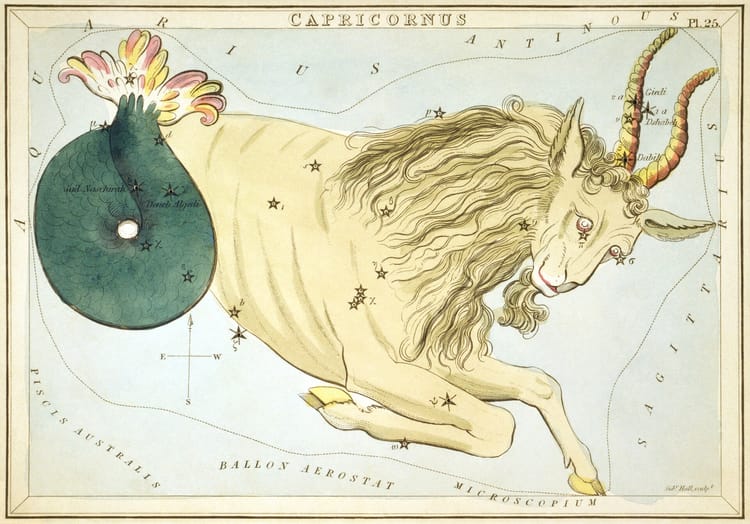

Another star I associate with the upcoming solstice is Antares, and this also goes for the constellation Antares belongs to, Scorpio (Scorpius for the pedants). Currently, Scorpio makes its midnight crossing of the southern meridian on the summer solstice, eternally in opposition to Orion the Hunter in winter. The Greeks had enshrined Scorpio as the one monster who defeated Orion instead of the other way around, and it's clear this story was a way to build relation between these two prominent constellations that track across the southern sky all night long at different times of year.

For astrological purposes I and many others of course think of the midsummer buildup and aftermath as Gemini season and Cancer season, but leaving traditional associations aside I also regard this upcoming time as a major annual window to connect with Scorpio. One of the very first things I think of seeing on a steaming summer night, besides fireflies flashing on the edges of the woods, is Scorpio's head and pincers inevitably being visible somewhere to the south. I like this because although we often regard summer as a time of brightness and openness, Scorpio is such a chthonic, ecstatic part of the zodiac that seeing the constellation at summer's height is a potent reminder of how darkness is important in this season too, just as light is important in winter. The binaries are wrapped up in one another yet again.

I am also simply fond of Scorpio as a token for all people of my generation, born with Pluto in that sign. That planet[6] is in its zodiacal home, but this brings both great power and great challenge. Our inheritance is collapse.

Caer Wydion

Just east of Scorpio is Sagittarius, and it is in this constellation that the galactic center is concentrated. That is: the Milky Way stretches in a band that for me in this hemisphere runs through Aquila, Cygnus, and beyond; but the more visible that Sagittarius is in particular, the more prominently we can see the features we most associate with the "Milky Way" as such. My region is now entering the time when, leaving light pollution aside, Milky Way viewings are at their best. If I drive just an hour northwest, I should be able to see it on a cloudless night.

I briefly touched on this feature of the summer night sky in my last astrolomy post, but to speak more of it now, in Cymric folklore this is Caer Wydion, the Fortress of Gwydion the wizard, who is either heroic or villainous depending on your perception, perhaps closer to a trickster figure. He may also be either a god or a mortal, depending on how you interpret the Mabinogion's origins. I've known his association with the Milky Way for a long while, but what I have yet to learn — if anyone still knows — why the galactic center bore such a name for my ancestors.

The name implies that Gwydion lives there, but does anyone else? What's supposed to be within? What lost stories involve this abode? Generally with the stories I know Gwydion from, he's either in the court of his uncle King Math or he's out and about in the world.

The trinity

I have just mentioned Aquila and Cygnus, two other constellations that the Milky Way passes through. The brightest stars of each constellation are respectively Altair and Deneb; adding Vega, the brightest star of Lyra, forms the asterism[7] known as the Summer Triangle.

Deneb and Vega lie far enough north that there is a substantial stretch of the year where they are each visible all night, Deneb especially. Altair passes much more from due east to due west (not quite, but close enough), so he has a shorter window, and hence why the Summer Triangle is of the summer: it becomes most prominent starting around now, seeming to accompany Scorpio but more directly overhead.

I value and track all three of these stars in their own right, but I also enjoy this celestial season when they're seen as a larger unit. The number three of course bears massive cross-cultural (spi)ritual, magical, and mathematical meanings. I wonder what non-Christian tales we might weave in our time for Vega, Deneb, and Altair as a sacred trinity.

The Perseids

The last summer event of great significance to me, besides Sirius' return, is the Perseid meteor shower. It falls directly between my birthday and my owner's, and besides being a simply brilliant shower, one of the best each year, I think it ties us together in a more-than-symbolic way.

For not only is there the calendar coincidence, but once upon a time, more than a decade ago, I was in that very abusive, unsafe, damaging relationship that left me with not all but much of the trauma that I have been working to heal myself from ever since. Just a week before I finally ended things, the Perseids came. I had already met the young man who would become my owner, and though we were attracted to one another, neither of us would be ready to admit it for a few more months. First I had to walk away from the person who was doing me such great harm. And I was in such abject despair that month, when I stepped outside to try watching the meteor shower, I didn't see anything special for a while, and I began to weep and plead with the firmament to show me at least one meteor. I needed to see at least one in order to have any hope that I was going to be all right, that there was any way out of my fear and pain.

There was one single shooting star. I made a wish. The rest is history.

Grounded in the sky

Compared to my trepidation about the art post I'd planned, I felt quite confident writing this, and I'm not surprised. After eight months of star-tracking and generally paying even more attention to the night sky than I used to, I've been glad to realize that something else I wished for has come true: I'm increasingly quite capable of orienting myself outside at night, provided the clouds hold off. It's not even necessary to find Polaris and thus know which way is north; I can examine the stars I do see (Polaris can actually be a bit faint here), know a number of them by name, and cross-reference them with the season to know what time of night it is, or conversely cross-reference them with the time to know the season, and overall be quite confident in my cardinal directions without the Sun to guide me.

I am grateful to have accessed this ancient skill, and with a few more years of practice I think I would be happy to heavily mentor someone else in the same thing. In the meantime, again I may repeat a post like this for some other season down the line. For today and tonight, though: praise the stars of summer!

[1] As I've mentioned before, my mother moved there when she retired, so although I don't have family from Iceland, the island is starting to feel like a very occasional home-away-from-home, and I would love to develop more than a mere tourist's relationship to it.

[2] Trouble with night vision adjustment was also aggravated by a couple of distant streetlamps and by neighbors who obliviously had all their outdoor night lights on.

[3] I'm not a devoted fan, but The Golden Compass was a beautiful read in my early adulthood and it did very obliquely inspire some of my satanism.

[4] A reasonably concise, refreshingly low-tech source: http://www.vikinganswerlady.com/njordrljos.shtml

[5] Of course this is entirely knowable, but as mentioned in past posts I'm trying to treat my star-tracking as though I am a human in a culture who does not have written records available for me to learn from, and I learn new things night after night instead, even as I technically look at astronomy software in addition to real stargazing.

[6] Astrologically speaking.

[7] An asterism is a star formation that extends beyond the bounds of a traditional constellation to encompass stars from several; it can also be a star formation within a single constellation that doesn't comprise the whole constellation, such as the Big Dipper within Ursa Major. Asterisms are a convenient shorthand for talking about star shapes that are more visible despite light pollution, whereas many actual constellations cannot be seen in full without a very dark sky by modern standards.

Thank you for bearing with the change in subject. I remain quite committed to next week's post, which is for paid subscribers only and concerns the mode in which death work and kink intersect through extremely high-risk kink activities. The week afterward, I will take a deep breath and examine the deservedly contentious realm of "womb magic," laying out the unfortunate reactionary politics therein and reflecting on how I try to honor that part of my anatomy without casting myself as a binary woman or regarding wombs as necessary (or sufficient) for womanhood.

Member discussion