First Quarter: Willow, alder, birch

It's Friday. Hello.

Today I have less philosophy and more celebration — not only because I've wanted to pivot from didactic writing toward the more broadly reflective tone I've intended to use, but also because celebration will often be in the nature of posts for the moon's first quarter. As the moon's light has waxed to the point where crescent will soon become gibbous, the night is brighter by a noticeable degree, and the energy of the earth itself seems to increase. We can move around more, do more, before the time comes to sleep.

Symbolically or otherwise, this is the time in my rites for doing the most with the fully material realm, whether that means crafting things by hand, playing with chemistry in the kitchen, taking care of other pragmatic needs in the home, tending to the garden, or as I'll do today, delving into wild nature and seeing what it offers us, foraging in various senses. I'll come back to this point time and time again: I can't say I believe that the moon above influences affairs below in a physical way beyond the ocean tides, but my interest isn't in obeying the moon as though there were some dogma imposed upon me, as though doing certain things during the "wrong" phase will court disaster. I'm not trying to act superstitiously. I'm only finding a life rhythm that makes sense to me, and I'd rather this rhythm arise in a kind of harmony with the moon (and even moreso with the sun, my king) than with the constructs of capital and industry.

So today, with the first quarter just recently past, I meditate on the gifts of the earth.

Hedgecraft

In some witch or witchlike circles there's a discipline called hedgecraft, for which I was long an unwitting disciple and over the last few years have decided to embrace more directly. Sometimes I've struggled to distinguish hedgecraft from herbalism, as the point of a hedge witch often seems to be that you know a lot about plants and what can be done with them in folk medicine; but I think I ultimately see herbalism as a practice wherein you predominantly focus on the medicine part, with or without any folklore or ecological thinking thrown in, and although I'm actually pro-herbalism in the right contexts, I'm skeptical and concerned about certain ways that it tends to appear in our modern society. The few self-described hedge witches I've known personally do practice herbalism, but their deepest interest seems to lie in studying the place that specific plants occupy — in the human communities where they grow today, in the historical communities that may once have relied on them more, and in the food chains and ecosystems they occupy with or without human involvement.

Or maybe that's simply where my deepest interest with plants lies. I love plants less for their utility to other beings, and more for their mere existence. So despite overcoming many years of thinking I wasn't a "natural gardener" and starting to garden and meeting with modest success so far — despite seeing intense merit in my household growing food and herbs and flowers ourselves in order to live more off-grid if/when necessary — I can't say the thing in the forefront of my mind with gardening is anything about encouraging a productive yield or guaranteeing that I'll always have certain plants forever. I care about those things abstractly, but my main train of thought probably centers more on keeping an ecosystem going, on just making sure that plants growing on the land where I live are doing well, aren't overwhelming other plants, and are playing a good role in the overall environment (which includes providing utility for my household, but I appreciate relatively "useless" plants just as much if they aren't invasive). I need to get better about things like watering and composting, as I've witnessed firsthand how failing to manage those properly can kill a formerly healthy plant or result in seeds never sprouting, but I would also say that half our achievements in gardening so far can be attributed to simply taking a hands-off approach and focusing on growing things that naturally do well on this exact plot of land. Agriculture doesn't have to despoil the world, regardless of what some arch-primitivists would argue, yet I do think many (not all) agricultural and ecological problems derive from people trying to grow the wrong things in the wrong places.

In turn, though I like gardening, I've been arguably more interested in learning to forage, even if the learning curve is steeper in terms of recognizing safe and unsafe species, knowing how to collect and use them, and actually putting in the work to find and process them. Over the past few years I've gradually learned a decent amount about theories of foraging and recommended best practices, and for as long as I can remember I've been a collector of information about wild plants, especially those common to my region that sits squarely amid Northeastern temperate broadleaf and mixed forest while occupying a liminal zone between maritime lowland and Appalachian highland. I love the idea of excuses to hike beyond "hiking is good" (it is, of course), I love the notion of gathering my food from whatever's available right around me, and everything I've read from both indigenous and non-indigenous sources suggests to me that this is the most sustainable way of eating imaginable, as long as you carefully time your foraging sessions and take only what you reasonably need before your next visit; this applies to hunting and fishing, too, by the way, but I'm going to save my thoughts about ethical animal use for another time. In any case, however, even my enormous love for foraging as a concept has not yet translated to foraging on a regular basis. I'm still an amateur and I aim to diligently avoid framing anything I know or think about plants as being some sort of advice for other people unless I'm absolutely confident I can give it.

For reference, I can count the number of wild (i.e. not deliberately cultivated) plants I've eaten or made other use of so far on probably one hand. I've taken bites of wood sorrel, sheep sorrel, and broadleaf plantain; they all taste delightful. I harvested great mullein leaves this last summer and made an experimental tea out of them; and this autumn I harvested the remaining stalk, which my owner and I turned into a hag's taper, something I'll write about later. I don't think I've done anything else that would really count as foraging, not yet. My owner and I can confidently identify hen-of-the-woods mushrooms, but we haven't had a chance to collect any. This summer I discovered that, like milkweed, an Eastern black nightshade species growing near our driveway is in fact not particularly toxic and warnings about toxicity really do come from conflations with deadly nightshade (which is not black nightshade) turning into misinformation, in the same way that there are just as many gravely incorrect rumors about certain dangerous plants being safe to eat; despite the Wikipedia links I've given here to explain which plants I'm talking about, I do not use Wikipedia for the final word on whether a plant is safe to consume or touch. It has incredibly biased information added from both overly credulous people and people who are skeptical as an ideology rather than as a habit. In any event, I still didn't try eating any of the black nightshade berries this year, because it still felt like too much of a mindfuck.

But for all my lack of direct experience, I am a writer. Writers are, I think, the supreme example of people who can admire, loathe, and in either case effectively discuss at great length many topics that we've come to know about simply because we know something and have a reaction to it. The worst scenario here is of course the writer who doesn't even know very much about something but still thinks they have something worth saying. Twitter hot takes were, I'm convinced, invented by writers. More positively, however, there is the writer as bard: as the figure who elevates humble things, as the figure who shapes narratives, as the worshipful giver of praise. Thus I've chosen to write about plants first and foremost as things worth praising.

Tree lore

The place where my hedgecraft-aligned praise begins: trees.

I choose to focus especially (though not exclusively) on trees out of both personal and cultural significance.

The personal: I grew up in the woods — not in the sense of living somewhere so rural that my family had no neighbors for miles, but I mean quite literally that the house I spent most of my youth in was part of several small developments plunked down in some of the town's northern mixed forest. Being at home meant being on a two-acre lot where I could see neighbors' houses but only through a fairly dense growth of red pines, oaks, maples, birches, and then an understory of saplings and brambles. Then, when I went to college this was a campus with heavy tree cover, and I lived in a forest-encircled apartment nearby too. After graduating, I spent nine years living in the Boston area — a wholly urban, relatively tree-free environment — but since mid-2018, my owner and I have been back living a town or two away from where I grew up, with woodland or outright forest right in the backyard of our last rental and now of our house. It would feel very strange for me to live somewhere that didn't have a lot of trees, and it feels nearly as strange for me to visit places without them. Though I can certainly find those places beautiful in their own fashions, trees mean home to me. I'm not particularly good at climbing them, but to feel their cooling shade in summer is a gift, and to experience a silent forest in winter is intoxicating. It's no accident that I love Tolkienian fantasy beings like ents and wood elves, or that one of the earliest ecological problems that ever stirred me particularly hard was the devastation of the Amazon.

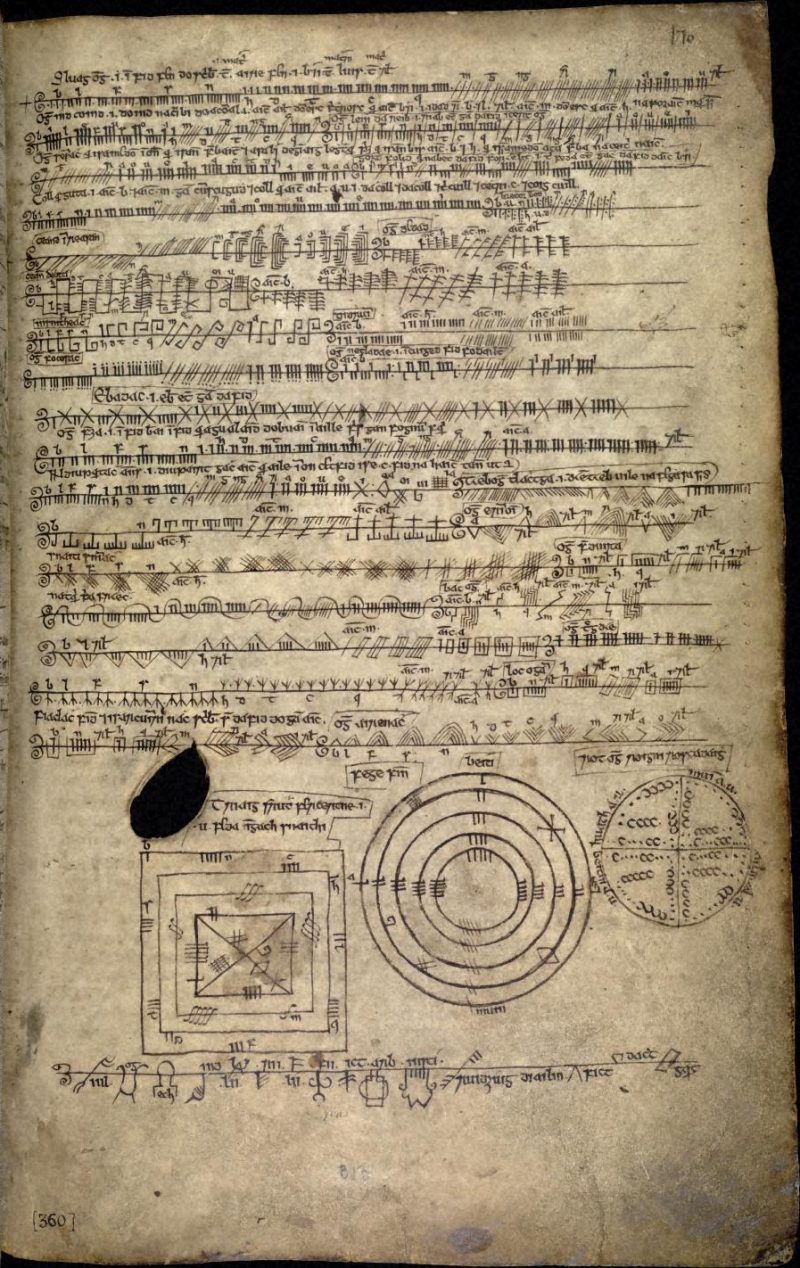

The cultural: from birth I speak English, and for better or worse I'm an anglicized person, and though folklore around trees was hardly unique to medieval English communities, I certainly have been influenced (probably including in ways I don't even realize) by the particulars of English culture regarding the symbolic or practical importance of certain trees and woods; above and beyond this, the ancestors to whom I feel most connected were and are Celts, whose lore around trees has been meta-mythologized in its own right. Celtic tree lore is itself not unique — I try very hard to resist essentialist stereotypes that gloss over the explosive amount of ethnobotanical lore available in cultures which are still actively indigenous or at least haven't been largely subsumed into whiteness — but I understand why many people do posit some sort of special connection between ancient Celts and trees, as I do feel fascination about how nakedly that connection is suggested by the archaeological/historiographic record while it simultaneously remains unexplained due to Celtic peoples' lack of pre-Christian written records and due to their oral tradition being severed over the course of Roman, English[1], and later invasions. Ironically, the strongest suggestion of magical Celtic tree lore comes from the one Celtic writing system that seems to have anyone in agreement Celts invented by themselves: ogham, the Irish "tree letters."

Ogham holds only a kind of limited value for me, insofar as I have no Irish family that I know of; although for a number of reasons I don't believe that having x ethnic background is relevant in terms of "blood" — oh hell, such a dangerous concept — I appreciate and support the common indigenous perspective I've encountered, which is that belonging to a given ethnic community is really about whether you were brought up with their traditions or not. (In other words, white people can claim they have a Tsalagi/Cherokee great-grandma until the cows come home, but this doesn't mean much if they were never raised with explicitly Tsalagi/Cherokee traditions.) I don't think the historical relationship between the Welsh and the Irish is such that I need to have any concern about appropriating Irish culture, but I quite simply find that because I was raised by a partly Welsh family with a distinct and serious sense of Welshness, I feel myself rooted most in the Brythonic flavor of Celtic communities — so cultural tokens of Wales, Cornwall, the Scottish lowlands identified by the Welsh as the Old North, and to a lesser extent Brittany. By comparison, Gaelic things — the cultural tokens of Ireland, the Scottish highlands, and the Isle of Man — hold less emotional or mental resonance.

Nevertheless, at least ogham is something, a glimpse of a possible pan-Celtic past that frequently seems unrecoverable beyond Ireland. There are even Ogham inscriptions found in Wales, especially Pembrokeshire — still usually using primitive Irish, thus implying an appearance through Irish raiding and settlement of the eventually-Welsh coast during the post-Roman period, but I've read of tantalizing cases wherein such Wales-located ogham examples at least present primitive Welsh/Common Brittonic names (or British Latin ones) and therefore indicate a brief time period in which the ancestors to the modern Welsh may have been experimenting with using a non-Roman writing system. That said, if there's any pan-Celtic quality to ogham's history, I don't mean it in terms of the orthography itself — I really think that before Roman invasion, most Celts probably didn't write — but I mean rather that the long-running folkloric association of each ogham letter with a particular tree species (and thus with various mythic symbolism) begs the question of what ancient Celtic tree lore these associations may or may not have sprung from.

As I sing a song for favorite trees, I may well draw on what I know about ogham. But I will likely sing of many other things that go into what makes each tree so special, beautiful, and important to both humans and the rest of the planet. The trees I've chosen today are in many respects quite different from each other not only in terms of folklore but in terms of general appearance and functions. However, they also share wonderfully distinctive things in common along the axes of kink, ordeal, and metaphorical or literal healing.

Willow

Is willow the tree of pain?

Certain willows we say are weeping. Willows are named sorrowfully in translations of Jewish/Christian[2] scripture:

By the rivers of Babylon — there we sat down and there we wept when we remembered Zion. On the willows there we hung up our harps. (Psalm 137:1-2, New Revised Standard Version)[3]

There is also the mournful willow of Shakespeare in the song of Desdemona, indeed willow suffuses Will's tragic heroines branching from the one — think of the famous painting of Ophelia and you may well imagine willows on the riverbank where she drowns, although I think there are in fact none.

I look at the English word willow itself. Its roots lie in old words for grass, or for twisting, but then there is Latin salix, whose origin is shared with word used in the tongue of my mother's mothers: helyg, akin in turn to Irish sail, and this name sail is given to the fourth letter of the ogham, for the sound /s/. And in Irish sail is associated both with willow and the kenning of "lifeless pallor." The Latin, the Welsh, and the Irish forms all come from *sal in Proto-Indo-European, or so it's speculated, we must guess always at these things, but they are good guesses. *sal- is then, in English, the origin of sallow.

Willow, sallow, sorrow. Beauty and ugliness. Sing all a green willow, my garland shall be.

But to all this, I sing of more. Although certainly being a willow species, weeping willow is not native to the lands where such words developed. It is not even native to the river banks of Babylon. Weeping willow: an export from China in the 18th century C.E. — the harps of Zion are, translated rightly, hung on a kind of poplar.

Despite literary and linguistic associations of sorrow and sickliness, willow's bark gives us an almighty, non-addictive pain killer and reducer of inflammation: salicylic acid. Salicylic acid: precursor and metabolite for the chemical we call aspirin. Even in its original form, I apply it on my face several times a week as it's an ingredient in commercial products to treat my acne. I would not simply use raw white willow bark as medicine — I do not have the requisite knowledge or tools to measure the appropriate dose, and I do not have the local indigenous knowledge useful for identifying which willows near me have safe and useful amounts of salicylic acid. But people with greater awareness and training — or conversely people with less common sense — will not only speak of willow as a historical medicine, but use it, and in the case of trained people they might even meet with success. In my position, I will reduce pain, swelling, and fever with something precision-crafted and tested, because although white willow bark might produce less adverse side effects than aspirin, it's also far less potent; but if I ever lost access to pharmaceuticals, I would possibly try an unprocessed willow bark formulation for lack of alternatives. (Although in my personal case, as I believe my mother is allergic to aspirin, I've always avoided ingesting it and know that willow bark is similarly contraindicated. For NSAIDs, ibuprofen is my real choice.)

Is willow perhaps not painful, but instead a healer of pain?

The dose makes the poison. Salicylic acid and its derivatives are well tolerated enough by most humans that overdose would have to be a deliberate act, but in smaller animals a single aspirin pill can be deadly, and pet owners are advised not to keep willow plants anywhere that their animals might be inclined to lick or nibble. In the medicine, poison always reamins.

And then there is the kink of willow. Remember many a switch — the punitive kind — made from willow branches. Process the branch and you have the pain killer. Swing the branch and you may inflict misery.

Willow is the tree of pain, but I sing willow as a mysterious dyad again, the giver of pain and the taker-away.

There are willow's other gifts as well. I sing for the pussy willow, for me a sacred plant whose catkins tell us of coming spring, symbol of Ostara. I sing for wicker, which may be made of many woods but is often willow. Willow, source of baskets, ancient weaving fiber, o willow.

Willow loves shade, and willow loves water. In times to come, I hope it will survive heightened droughts and stay with us.

Alder

We may find salicylic acid in another tree's bark, so in surviving ordeal and healing from trauma, I see this tree as another potent symbol: alder.

Alders are peculiar, rife with their own folklore, not so much of sorrow as that of red rage — their wood being reddish — and red being so often tied to war. Fitting then that I've read of alder shields in the past, and that the ogham kenning for the letter fearn (alder) can be "vanguard of warriors."

I've been learning about alder more recently than willow, because we have alder species in my region, but I'm bad at recognizing them. My song here is thus more brief. Consider this a vow to learn more, especially as it's one tree that's also a source of tannins; it would be revered by traditional tanners and leatherworkers.

Leather. Kink again.

Like willow again, although there is no close relation, alder likes to grow near water. I hope this tree, too, will nonetheless survive coming droughts in many areas, most of all because I've learned it plays a large role in forests' nitrogen cycles.

Birch

I return to a relative of alder that's also a tree used for switches. But unlike alder or willow, birch is not so much a pain killer. For me it's less earthly, more unearthly.

Otherworldly.

Birch, I sing to you directly because you are so dear to me, so revered. Your white bark, paper bark, your black jagged markings like wounds. You rise in young woods, eventually overwhelmed by mightier, hardier brethren; but sometimes you also grow in vast stands of your own, hallowed ghostly groves that catch naked golden winter sun or contrast with the flush of summer's green.

From what I can tell, just as you are sacred to many people now, so were you sacred to my own ancestors. Among the trees of the Druid cult, surely you were held in high esteem, even if it is not plainly written. There are the Celtic legends speaking of birch growing in the Otherworld, suggesting some article of old animist faith surviving or intertwining with Christian conversion. There are the traditional May poles of certain communities who mark some sort of May Day — not always a birch, but where the people of Cymru[4] have long been concerned, birch is often the choice.

We have painted birch trees over our marriage bed. I have a wand of birch, carved by my hedge witch friend. The wand is one of my four ceremonial tools.

Birch, whistling swinging switch and spirit of life-death, known-unknown, mystery.

Despite my own associations, I know that the birch has plenty of practical uses as well. A good firewood, a good wood for furniture and plywood, a good bark for certain indigenous construction techniques (for homes, canoes, and more). People can make tar from birch. Birch yields sap for syrup. Even though I don't know how to do these things with birch myself, I love that the tree is worth more than its appearance or associations. Nothing in nature is.

Birches are another drought-vulnerable tree. Changes in climate are also enabling birch's pests to damage it more. I loathe to imagine losing this tree in the coming times.

But as with the other trees I've sung for today, I think the first step to protecting it is to cultivate even more reverence. To let it bring me not pain, but joy.

[1] Throughout future writings I intend to try simply referring to the original Germanic settlers of England by the term English instead of phrases like "Old English" (correct for describing their language, but I doubt the people themselves would have identified as "old") or "Anglo-Saxon" (still a common choice among scholars and laypersons alike, but fundamentally loaded with racialist/racist ideology in its development as a phrase). Being Welsh, I've been equally tempted to just say "Saxon" insofar as in the Welsh language a root meaning "Saxon" is how you refer to English people, culture, and language; but I think that when saying Saxon in English even eliminating the Anglo- prefix fails to remove the racializing connotation (it might make that worse) unless you're talking very specifically about Saxons as a distinct group from the Angles. Anyway, I may change my mind around all of this, but for the moment, I speak of any past, present, or future culturally-dominant inhabitants of the place we call England as "English."

[2] In keeping with trying to use words that make the most sense to me and are also the least negatively loaded, I intend to always specify Judaism, Christianity, or Islam (and for that matter the Baháʼí faith, Druzism, Samaritanism, or Rastafari) rather than attempt to group them as "Judeo-Christian" or "Abrahamic" religions. The worst case scenario with those groupings is that they have the potential for (and some history of) being used in contexts that understandably upset some members of the religions in those groupings which are by and large persecuted by Christians when existing in a hegemonically Christian society. Even in a best case scenario that assumes good intentions on everyone's part, I encounter all sorts of situations where someone's claiming to generalize about "Judeo-Christianity" when really they're only saying something about Judaism or Christianity, not both, or they claim to generalize about "Abrahamic religion" when what they're saying still only selectively applies to particular faiths claiming Abraham as a patriarchal figure. So if I mean to say something about just Christianity and not anything else, I will say Christianity; if I mean to say something about Christianity and Islam but not Judaism, I will say Christianity/Islam; and if I mean to say something about Judaism and Christianity, I will say Judaism/Christianity, but not Judeo-Christianity.

[3] Contrary to the fact that I'm not comfortable belonging to an organized religion, and to the fact that I have a satanic alignment — there will probably be citations throughout this newsletter from various religious texts, for various reasons. For the record, for Christian scripture (and Jewish scripture reinterpreted by Christians) I will usually be making use of the Bible I used when I was briefly Catholic, ergo the New Revised Standard Version with the Apocrypha. This translation is generally fine for my purposes particularly since I still approach Christianity with a Catholic flavor of familiarity. However, if I ever want a more purely dramatic flavor I'll gladly pull from the King James, and if I'm ever dealing with a "biblical" text that needs to be presented in exclusively in its original Jewish context, I'm already overdue to ask some friends for recommendations on a good translation of just the Tanakh.

[4] Cymru is the Welsh name for Wales. I hope, increasingly, to use that name exclusively over "Wales," but I want to ease unfamiliar readers into it. To pronounce it, you can usually just say "KUM-ree."

Every time I try to make a post shorter, so far it doesn't work. To some extent I will blame my natural tendencies, but I also suspect it's that even when I'm trying to write something less didactic, in the newsletter's early stages I'm still obliged to explain why I'm going to write what I'm writing. This lengthier habit may therefore continue for at least another 1 to 9 weeks, regardless of exact topic. But thank you for staying with me so far, and I hope you're enjoying things even if it takes you some time to get through what I've written. Remember, too, that paying just $1 every month makes this writing more worth my time and opens up comments right here — but if that's not affordable or worthwhile for you, honestly I would love to read or hear your reactions by whatever other means you may have of contacting me (which, going by the current readership, are largely people who found me first through my local kink community, FetLife, or Mastodon). Sound off in those other places if you like. I love talking about all of these things, constantly.

Member discussion