First Quarter: The homestead & the commune

Hello. It's Friday. I had a fairly terrible start to this week, but it took several upturns yesterday, and now I happen to find myself in an almost unusually relaxed frame of mind (which I may get to explain later, but I'm not ready yet). I hope you have some chance to feel the same.

It goes without saying that most people I'm close with or even tangentially acquainted with are coping with mental health challenges, many centered around or at least caused by the festering wounds of capitalism and its underlings. This week's surprising improvement notwithstanding, of course I share these friends' position; it's a major reason I decided to focus Salt for the Eclipse in certain directions. What I'm writing about today is now one of the most pervasive symptoms I see from my peers' and my own suffering — and one of the gateways into this newsletter's last founding principle. This symptom, this gateway, can be written as a single sentence, a quotation attributable to no one person.

I just want some land where I can run away with all my friends and start a commune.

The meme

I have heard the above quote so many times in the last 5-10 years, from so many people, that I couldn't possibly tally everything up; and its frequency practically invites parody. At this point it might not be an individual sentiment so much as a meme. In my own circles, the sentence is often modified by highlighting queer friends or a queer commune, but this is not just a dream of us queers. The cottagecore trend on social media is a related example, along with homesteading blogs; these things seem to vary in how much they emphasize the communal part of an off-grid, self-sufficient agrarian lifestyle, but I'll get to that in a few paragraphs. And although I know that I tend to hear the pro-homestead/commune sentiment from people who are especially beaten down by knowing about the state of things around the globe — people who are, to use a phrase that I consider non-ironic, terminally online[1] — a good deal of the people I've known/known of who actually go so far as to start homesteads are not online nearly as much as they're offline. Such individuals may either have stopped being online or were never very online to begin with; whichever the case may be, there's one very simple explanation for why they can't be very online now, which is that operating a homestead takes a staggering amount of time and attention (not to mention up-front resources, which I'll return to later as well). Despite such effort, I've never heard or read any reports from homesteaders who find the work anything less than incredibly healing and rewarding, at least if they haven't been burnt out by external factors.

The healing and rewarding possibilities of "running away" or otherwise cloistering oneself in a smaller group of peers on a special plot of land: does such appeal simply come from having an excuse to finally shut out the clamor of white noise from terrifying news and hateful people, to concentrate instead on simple practices and shared values? I believe such considerations do play a role here. When I myself feel the urge for a homestead and/or commune setup, there's a monastic quality about it. And a tribal quality — as I've written in the past and will write again, humans have still not evolved to empathically connect with more than about a hundred other people, therefore our deepest instinct is still to organize ourselves into communities no larger than that size.

But these considerations do not explain why the contemporary homestead/commune urge refers to an essentially rural lifestyle — or, if urban possibilities are put forward, why the homestead aspect still manifests through city houses with chickens in the backyard, or apartment complexes with gardens on the rooftops, or broader solarpunk dreams of green cities where trees outnumber buildings. To address the true core of homesteading and intentional communes, I always think of the broader picture of radical movements that can be encapsulated by another meme:

"Back to the land"

It is not new for lots of people who don't have their own homestead to find themselves wanting one. There have been iterations of this ever since societies began industrializing, and going back even before that — ever since the progression of private land enclosure as a component of early capitalism.

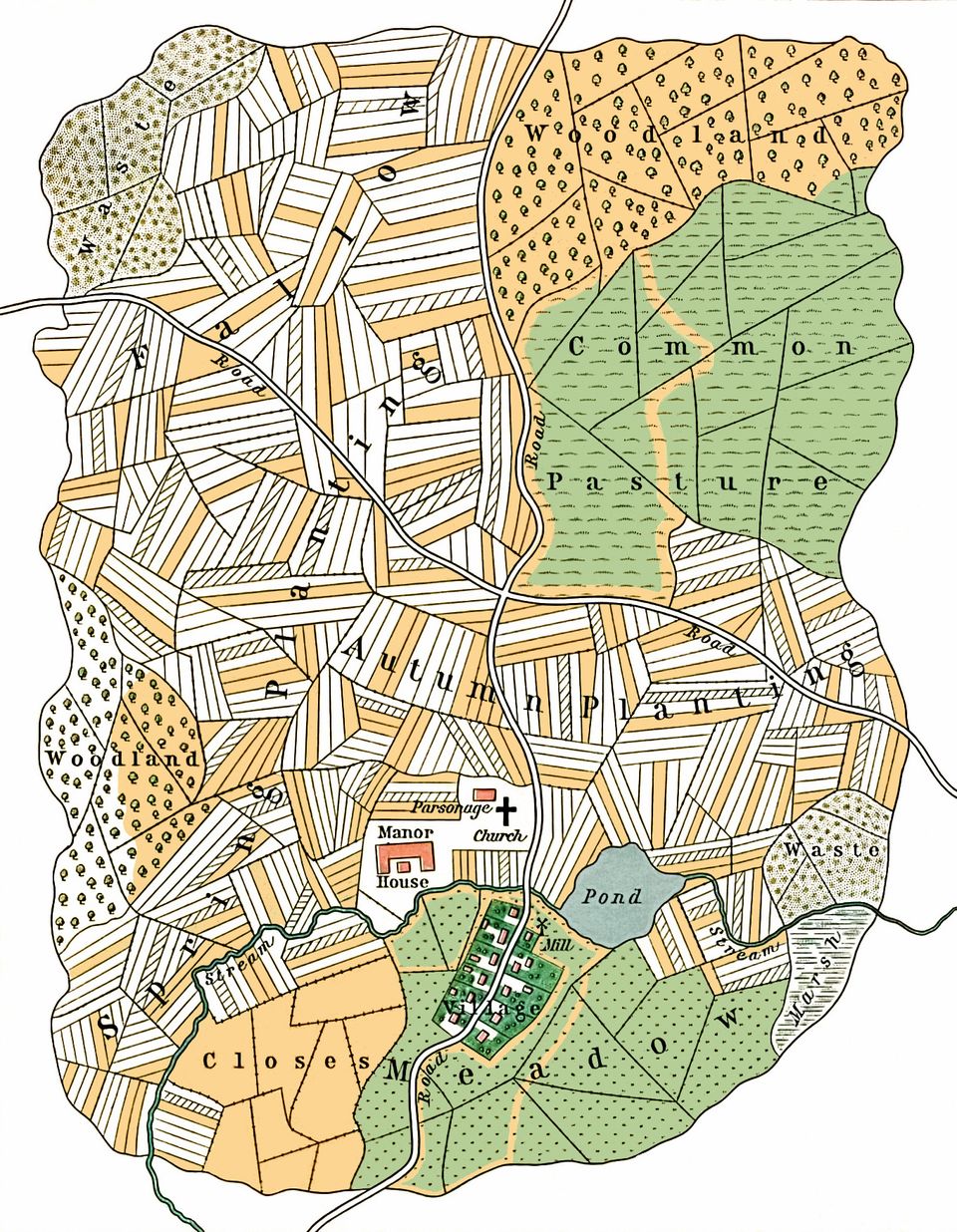

Let me get into some history in case you're not aware of what I'm referring to. Virtually anywhere you go in the world, but focusing on early-modern Europe as capitalism's epicenter, a pre-capitalist socioeconomic structure would be signified through most people working (or hunting and foraging from) their surrounding land in order to survive, not working for a wage to convert into purchased goods and services for survival. The land available for this subsistence purpose was not all public, for instance certainly not Britain's royal forests in the feudal era; but crucial portions remained public, not in the sense of being owned by a state institution but in the sense of being held in common by the people.

It's hard to wrap one's head around some aspects of this common land — the commons for us anglophones — because sometimes it really didn't belong to anyone on paper, but frequently the commons would also refer to manors and other forms of nobility-controlled land, where peasants rented and paid this rent by turning over to their feudal landlord an annual portion of their livestock or harvest. Many of these tenant peasants, called serfs, were borderline slaves often trying to work off a debt (and indeed the European feudal model grew out of slavery-reliant Rome). But free peasants also existed. Crucially, too, it's worth noting that depending on the exact place, time period, and landowner, the amount of rights and privileges — and the lack of close regulations — extended to serfs could be rather surprising compared to the kinds of restrictions that 21st century working-class tenants experience in their lease agreements, or that contemporary homeowners deal with if they've made the classic mistake of buying a house in an HOA. To make a broad but I hope mostly accurate generalization, the medieval European peasant experience typically offered a best case scenario where your livelihood depended on land that you[2] had a modicum of democratic(-ish) control over; a mid-case scenario where your livelihood did somewhat depend on turning over a fraction of your land's output but you had total control of your time and how you chose to work your own plot; and a worst-case scenario where even though your livelihood was subject to an asshole who either demanded too much output from you or failed to protect you from other invading assholes, your daily life still kept you in touch with the earth and the seasons, while you still had a communal social life with your fellows.

Whether this would be a necessarily or sufficiently liberating lifestyle is probably in the eye of the beholder. But no matter what, prior to introducing capitalism into an agrarian community, a universal constant is land-connectedness and a chance to develop an intimate relationship with the land on one's own terms, regardless of what other rules and laws one might also have to follow. And naturally in the case of pre-agrarian hunter/gatherer societies, most if not all land is basically held in common within a given tribal unit, especially if the people are nomadic — indeed here there's often the sense that humans can't own land so much as the land owns them.

Over the course of the late Middle Ages through the Victorian period, commonly held land — simply called the commons — was gradually subject to a practice referred to in English common law as enclosure. I am most personally versed in the history of enclosure as it happened in Britain, and that's what is usually taught to anglophones, but equivalent practices happened across Europe as capitalism's profit motive affected more and more people's thinking about the function of land. In the wake of the Black Death, many peasants had taken their labor away from their feudal lords and moved off that land into urban centers, and those peasants who remained could demand more rights and privileges than they had before because their labor was at a premium; whether a deliberate backlash to this or not, landowners repaid this maneuver by completely privatizing common land units, one after another, on the logic that they could generate more wealth for themselves by having total control over that land's output. When any sort of tenancy system was replicated now, it was in the return to slavery used by colonial plantations; colonized land was itself enclosed much of the time, apart from relics like we see in New England town commons; in Europe, over these centuries more and more people lost the opportunity to live off and with the land, especially during the 17th-19th centuries. Common land now persists in small pockets across various European countries, but in Britain's case for instance millions of common acreage has been swallowed up.

Despite enclosure's perceived victory, people did not like this. Early-modern European history is absolutely riddled with resistance efforts. Even while their relationship with their land might not have been the same as a hunter-gatherer's, the peasant class (turning gradually into the wage worker class we see today) were often under zero delusions about enclosure's absurd logic. For untold generations their ancestors had been permitted to drive pigs through particular woods, to rotate crops through particular fields, to tend particular apple orchards and keep a winter's worth of apples for themselves. In some cases the land was completely theirs to do with as they pleased; in other cases, it did belong to someone on paper, but it was the way of the world that ordinary, non-owning commoners could do something with that land. Now, through government acts and through the wealthiest landowners banding together as glorified bullies, the peasants were told in fits and starts that no, you couldn't use this land anymore at all, and you can't live on it either.

You have no home anymore. Get a job. Good luck finding one that will pay you enough to ever buy land for yourself.

People revolted in various ways over the centuries of enclosure. Spontaneously provoked riots were a popular option whenever a land dispute arose over people attempting to use private land that was previously held in common. There were also more intentional movements like the Diggers. Some historians and sociologists believe, and so do I as a general observer, that as these attempts failed, lower-class Europeans — i.e. most Europeans — developed a form of generational trauma around being robbed of their land, becoming ecologically dispossessed. Effectively, though they weren't colonized in the way we often learn that concept today[3], and though they would come to benefit from modern chattel slavery and the dispossession of indigenous peoples elsewhere in the world, enclosure was the keystone by which most European indigeneity, already damaged, would come to be destroyed.

This had reactionary effects and also revolutionary ones. Landless Europeans clung to the ideology of colonial settlement as a solution for their trauma even as they now weaponized this longing against other cultures and traumatized them in turn. But simultaneously, once industrialization was introduced, the Luddites reacted to the technological angle — and the Romantic movement in "Western" art was born, packed with a craving for all things natural. Paganism as a deliberate religious framework came out of Romanticism. So did ethnonationalism that would fuel legitimately necessary self-determination movements for marginalized ethnicities — but also would, by the early 20th century, lay the groundwork for fascism. To me, fascism is not just capitalism in crisis, but an inevitable result of capitalism as capitalism is crisis, constantly manufactures crisis, runs on the byproducts of crisis. Simultaneously, a progressive backlash to that crisis is also inevitable, and will occur again and again; the 19th century was flush with religious communes going "back to the land," and in living memory we have hippies starting communes within the upheaval of the 1960s-1970s.

Tradwives & unicorn ranches

We are in a fresh wave of the same phenomenon. I do not think it's coincidence that the contemporary homestead trend is often stereotyped as being a "white" thing; people whose ancestors assimilated with white identity are so often looking now for a sense of landedness that most of them haven't really had for centuries. Simultaneously, people whose ancestors were more recently colonized or enslaved by white people are now frequently erased in homestead narratives. In the Americas, it's uncomfortable for most white homesteaders to acknowledge they're working land that they only hold as occupiers, or that might once have been worked by slaves. Maybe even by their own ancestors' slaves, given that in order to afford a homestead most white people who do it are benefited by generational wealth of some kind, and it's a roll of the dice how much of that wealth came from truly despicable sources. And meanwhile, across the globe there are people of color and/or indigenous people who still frequently don't have the option to homestead as easily as white and/or settler-class people do.

But even after accounting for these problems, all sorts of people want to live off of the land again today. For every luxury homesteader on their Instagram, there are all the people who are both materially and psychologically dispossessed of land, whether due to centuries-old enclosure practices or due to more recent abuses, who dream of homesteading not as an #aspiration but as a sacred right. If the wave of people desiring this is not its biggest yet, I wouldn't be surprised if it did become the biggest over time, given the stakes we're facing environmentally and sociopolitically.

Unfortunately, as with the mixed reactionary and revolutionary outcome of enclosure and industrialization mentioned a few paragraphs up, the homestead/commune urge does not come laden with entirely positive moral weight, as far as I'm concerned. Homesteading — especially on land usually defined as belonging to the United States — has a right-wing reputation when it comes in the forms of survivalist bunkers packed with more guns and ammunition than a single family could use in a lifetime. On the commune level, it's hard not to think of Christian fundamentalist compounds. Cottagecore aesthetics often receive criticism for not only their whiteness and bourgeois chic but also for going hand in hand with "tradwife" discourse — the modern slang for the choice some women make, whether as lifelong right-wingers or ex-leftists, to be traditional wives according to a hegemonic white patriarchal social model, making homes and making babies. The online right's catchphrase to "reject modernity, embrace tradition" links directly to the more dangerous faction of people choosing homesteading as an escape from wage labor.

But with that warning aside, I couldn't possibly say that the homestead/commune impulse is a poisonous one. With shared leftist, liberationist, anti-authoritarian values, any such environment may still be at risk of petty infighting or personality cult takeovers, but at this point in my life I can't see how at least attempting to create such a space is any worse than allowing oneself to stay part of The System. For people who can break free as ethically as they can, I wish them luck. And I can dream of being among them one day.

Where are all the homesteads, all the communes?

By now this is the bigger question for me than whether homesteads/communes[4] are inherently good. If it were easy for everyone in this age to address their burgeoning dreams of such a lifestyle, then anyone who wanted this badly enough would have already gotten that project off the ground.

I've already touched on some of the systemic barriers, but here's what I encounter on a personal level, which may or may not apply to other people.

1. Land that is not mine to own

I have acknowledged this before but feel obliged to mention it again: I am a settler. Not the way that some are, insofar as half my family immigrated from Wales between one and three generations prior; but they are all white-privileged and have still benefited from colonialism indirectly, and on the other side of my family I have white-privileged ancestors who did directly take part in the original colonization of Québec and (as immigrating Prussian Jews) the California coastline. As much as I am relieved to — frankly unexpectedly — own a house and break out of renting from a modern landlord, I have mixed feelings about the land I live on, because I don't feel like it's mine, and the simple fact is it's not. I occupy it, but that's different. I try not to call it property, because although legally it is, I feel like the wiser outlook to take is that I am passing through here for x number of future years, with some pieces of paper that suggest I have the right to do so.

As long as I'm living in this house, I feel a responsibility to steward the land in order to help the ecosystem here and not contribute any more damage to it than past settlers have probably already caused. But this is not the same feeling as wanting a homestead here. I would rather establish a homestead on land that is not stolen from an entire people. I have no automatic judgment for fellow settlers who choose to establish deliberate homesteads in this country — we can't all just move abroad to ancestral homes, some of which we may not even know about, and what about the position of people who are not indigenous to this place but were brought here through slavery? — but if a local tribe sought to recover land from a non-indigenous homestead, what would those settlers' reaction be? "How dare you kick us off of here, we can't just give you our land"? I've encountered this attitude more than a few times. For more on it, let me link this paper. The upshot for me is that it may one day feel like the best choice (of a series of non-ideal choices) is to start a homestead or join a commune near where I already live, but even if I were to do so, I hope I'd be able to temper my enthusiasm for the project in a different way than if I were doing this in Wales.

2. Land that I couldn't even afford to buy from a wealthier colonizer

So yes, my owner and I have a house. But it is less than 2000 square feet, and more importantly there's less than an acre of land around it. The layout, solar positioning, etc. are such that gardening is possible, and with enough time and money my owner and I could probably get a good deal of produce and staple crops for just the two of us and maybe one child; but not remotely enough to suit all our annual needs. Likewise, under the right conditions we could probably raise chickens in our backyard, maybe even a goat or two, but those are pretty much the livestock limits for this plot. Immediately to either side of us, we have neighbors whose politics I would not trust if the shit hit the proverbial fan. Our town is at least a right-to-farm community, so I don't know of too many ordinances that would prevent us from doing just about any standard agricultural activity in a residential area; but all told, I can't say that where we're living right now is ideal homestead material.

To have enough land for what I'd call "feature-complete subsistence farming," we would need to sell this house and buy another with a barn and at least a few acres, more if we needed extensive livestock pasture. If we wanted to try a communal format, then we would need even more room to support food for even more people, plus room for all the extra living quarters. And depending on what exactly we'd be farming or otherwise off-gridding, we would need to account for the cost of buying or building facilities to process or generate various things.

Land with features like these — or the potential for them — is enclosed sharply enough here on the East Coast that to purchase it is laughably expensive. My owner and I are nowhere near the financial solvency to manage that. Speaking of which...

3. The nest egg required to quit existing work and put all the necessary work into the land I had

A favorite nonfiction book that I've read in the past few years is The Shepherd's Life by English shepherd James Rebanks. It's achingly beautiful and poignant, but one of Rebanks' goals — which he accomplishes very well — is to deglamorize and defetishize pastoral living. He is a proud shepherd because he has been in a shepherding family of many generations in the Lake District; but while he wholeheartedly prefers his relatively archaic lifestyle over a more modern one, he repeatedly points out how arduous it is. Some of the challenges come from how capitalism and tourism affect his area today, but many are universal to raising sheep in any location and time period, especially if you aren't wealthy by whatever standards of wealth your society uses. There are no days off.

Since becoming a homeowner I've found that even without also being a shepherd, taking care of a house and even just doing basic land stewardship is a preposterous amount of work — particularly if, like most houses, you come into one that's had certain repairs overdue for years, and if the land has been improperly maintained in the past. We had an inspection that indicated that this place was largely a "safe" purchase, and we've only had a few true surprises, but particularly in the first year since moving in I had moments of paralyzing anxiety about everything that still needed doing. Not just things that would be nice to do, but also things that are already kind of broken and will only get more broken over time. I was even overwhelmed by little things like cutting grass — we are anti-lawn, but we do have ticks and yellowjackets to discourage. Or the need to plant some ground cover — the past owner either planted the wrong kind of lawn grass or overworked its care, and now there are erosion problems and the soil is generally sandy and loose, thus at some point it behooves us to lay down either a native grass or some other kind of good soil fixer. And then there were the invasives. No plant is truly useless, but in our first summer we had to dig up pokeweed right next to the house.

It's been a lot to handle just these things when we both have two full-time jobs that don't pay us enough to properly get by and put money into savings. Working those jobs interferes with having the time to do certain things ourselves. Lacking money means we can't hire other people to do things for us. If we were to actually homestead, then presumably that would become our jobs, thus solving the time problem, but to get by for the first who knows how many years without other jobs — and to afford to make all the investments we needed on top of that — I can't even get my head around it.

4. Help from other people is a necessity

Part of the solution to the above problems is acknowledging that ultimately, it's foolish to try homesteading alone. "DIY" is a valuable philosophy for saving money (assuming that your up front cost for supplies isn't going to exceed paying a professional) but as much as humans did not evolve to function with an awareness of what thousands and millions of other humans are up to, humans also did not evolve to operate as completely self-sufficient nuclear families either. Even eliminating capitalism, even if all work were its own reward, people always need to devote about 11 hours of every 24-hour day to sleeping and eating. What else can each of us do with the remaining 13 hours? Not enough to take care of all our other needs. We need to help each other and accept help from each other. That's leaving aside any disabilities, too. And with multiple people throwing into a pot together, some land purchase goals become a lot more attainable.

Hence a communal mindset. But my owner and I don't yet live around people we'd trust enough to manage a commune. And even if some of our friends lived closer, there's a final impediment that I have to try and explain my feelings about without sounding too cynical, which is...

5. Communal living is actually not for just "you and all your friends"

Refusing to make tough decisions about who to collaborate with on a project of any significant scope, such as a homestead = a recipe for disaster. Particularly when starting out, for one thing you're likely to run into too many cooks spoiling the broth. You should only take on as many people as your decision-making process can meaningfully support, and you should only take on as many as your project itself can provide for even if the first few years go badly. You need a team of people who bring useful skills to the table, even if "useful" should have a broader definition than what capitalism mandates; if you still plan to support someone who can't provide a lot of support in return, you have to be serious about that and not ditch them when it becomes inconvenient. You need people around who you don't just like, but who you can tolerate being around for extremely long stretches of time, and whom you can have difficult conversations with, not just fun chats. You need people whose work ethos and communication styles align with your own, and if not, you need a system for resolving how they'll do things differently than you. You need people who you feel safe with in most circumstances, and you need the ability to set boundaries for the areas in which you wouldn't feel safe. And conversely, if you like and trust and fare well with all of these people extremely well, such as to the point of being in a polycule with them, you need to be prepared for how your activities together will be affected if some portion of this interconnected unit breaks up, or if someone else comes on board and isn't "one of you" in that respect.

I say all of this from trying to build other things from the ground up — not communes, but the same principles apply. And at the end of the day, most people's friends do not match all of the above criteria for all working on the same project together, never mind living together in the process. I'm quite certain that when we hear about commune drama among supposedly conscientious anarchists and what have you, it's often because not all of the above considerations were made, or considerations were made but not completely, or personalities changed.

Speaking with utmost respect for all my friends, I can think of probably less than a dozen whom I'd ever even consider asking to set up a communal homestead with my owner and I. Of them, supposing we could all wind up in the same place together, I think most or all of us would need training in certain areas to make the project viable.

And depending who exactly went in on this, I would feel varying degrees of openness toward how physically closely we might live together. I'm more extraverted than my owner is, but both of us are of a neurodivergent flavor where our actual domestic premises need to be just ours. We're in agreement that living in the same house with anyone else (besides kids and pets) is not an option for us. Sometimes I'm shocked that he and I cohabitate together as well as we do, because outside of him, I can't abide the notion of having a roommate, and in younger years fared horribly with them. Even when we were poor enough that living with roommates would have really helped us out (and arguably it could still help us now), that was just not happening. We stayed broke to preserve our mental well-being. In any case, a big queer commune house sounds like the bad kind of hell to us. We'd do much better somewhere with common farmland and social buildings but a few separated houses — with at least enough space between them where we wouldn't all hear each other having sex, and depending on the people, enough space to not constantly be aware of each other's comings and goings.

Sacred skills & vital lessons

Despite so many obstacles, right now my owner and I are still trying to realistically pursue certain homesteading goals within the constraints of where we currently live. We have no illusions about being well on the way to my owner's dream of a deer or alpaca farm, or my dream of an enormous herb garden (complete with poison plants!), or other fantasies of fruit orchards and grain fields; but maybe chickens really will happen here one day, and we can get some vegetable beds working over the next few years, and I slightly expand the one herb bed beyond its current form.

I won't speak for my owner in this regard, but I think that doing whatever's possible is worthwhile because I can envision a future in which I may need to practice subsistence skills whether I like it or not; I'd best learn them.

And with everything I do on this land that we "own," I try — surely imperfectly, but try — to remember that I am still an occupying entity, and I'm working on making time to pay it forward, to help directly with whatever would most benefit the original inhabitants who still very much live here. Even writing that last sentence, I'm not altogether comfortable, because it feels like bragging, or like I can meaningfully evaluate the impact of my actions against those of less self-aware settlers; awareness does not change much at the end of the day if you keep participating in the problem. I think what I'm really trying to say here is not that I'm doing the absolute right thing. It's just a thing that I'm doing. I hope it will turn out to be right.

Some of it is at least rite. The choice I've made is more grounding and calming and land-connected than doing nothing at all. It helps me establish safety in my personal environment, and it keeps my attention local, where it ought to be. I need to live this way somewhere, even when it's not my ideal "where." And the prospect of homesteading fits into a larger picture of elevated domestic work as a form of sacred ritual — I am no tradwife, but I agree with the feminist recognition that all work is work, and I am drawn to many domestic work types more than to other types.

So there will be times with Salt for the Eclipse where I write about taking care of a home, whether that comes with -stead at the end or not. And for the most homestead-like aspects, I will be unapologetic in my dreams for going back to the land. And maybe one day I'll get lucky enough for more of those dreams will come true. I just had to offer all this prologue in order to be clear that this isn't me simply paving the way to convert this newsletter into a cottagecore lifestyle diary. The past era that I grieve is not the time of the cottage. It's the time of the commons.

[1] I still can't wait to write out all of my thoughts about the internet — the parts I still love, the parts I increasingly loathe, and the relationship I've been cultivating with it for several years, my goal being to use it as much as possible for a few very specific things and then to avoid using it for practically anything else. I was once and in some lights still am terminally online, so when I use the phrase as criticism, it's very much in a "there but for the grace of fate go I" way.

[2] At least if you were recognized as a man.

[3] Of course European cultures had also been colonizing each other for millennia before they started branching out to colonize other continents (and "internal" colonialism had also taken place on those continents), but that's a topic for another post.

[4] I apologize for using both these words so often simultaneously, instead of bothering to consistently distinguish between what is a homestead and what is a commune. I am definitely aware that some people who start homesteads do not start them with a "communal" mindset at all; they really want to live a more introverted existence in the proverbial woods, or what have you. However, as I've implied throughout the rest of this post, I don't think that lone homesteaders do nearly as well for themselves as those who operate communally with others. I also think that almost no human is so antisocial enough to truly retreat from all other humans except their spouse and children (if they have any); and if they do, that's concerning. And lastly, I think most people imagining themselves to be "going it alone" with their survivalist bunker (or whatever) are deluding themselves insofar as in all likelihood they are still banding together with a few other folks of similar inclinations in their area, sharing information if not also certain resources; their commune may not look like a queer anarchist polycule commune, but they are still creating an intentional tribe based on certain principles.

Thanks very much for reading this megapost. For this one I have to offer a special thanks to the anti-racist organization White Awake, which I've found an invaluable resource for unlearning whiteness and doing meaningful anti-racist solidarity work; I could not have possibly framed much of this post the way that I did without information I specifically absorbed from teachers in one of WA's programs. If you are white or would describe yourself as benefiting from perceived whiteness, and if the portion of this post about the destruction of the European commons really spoke to you — or if you've just been hoping to find a good anti-racism course that productively tackles issues of white fragility — then I especially recommend taking their "Before We Were White" course, which unfortunately is just wrapping up for this year, but please think it over for later.

Next week: I'm going to finally let myself (a person of many genders over time) talk about gender, again while diving into the past. I'll see you then.

Member discussion