First Quarter: Sacred domesticity (a deeper delving)

Hello. It's Friday. The past couple of weeks have been hard for me but I hope they've been all right for you. I'm at least pulling through enough that I can still send today's missive.

For Calan Mai/May Day, I wrote a post about how all work is work, including domestic work. My focus was political — which is to say, my focus is always political, but sometimes that's clearer than other times — and I only brought in talk of the sacred toward the end. There I wrote in particular:

With so many vital parts of life happening there, the home is sacred, and so to care for the home is to also undertake a sacred duty. How many animist faiths have gods or spirits of the home? Many. Perhaps most. They're not a part of my own cosmology, but as a witch — especially as one drawn to kitchen witchcraft, and as a witch who needs an indoor "base of operations" for hedgecraft activities — I can't help but feel driven to include the rhythms of the home among my other rhythms. Domestic work is a daily, weekly, monthly, annual rite, unending and circular and cyclical, infinite. It may not be strictly "a woman's work," but as the saying goes, that work is never done, and although we might interpret that to negatively mean that homemakers work too much, positively we might also consider that as house chores never stop needing to be done, they mirror seasonal living and they remind us that time is a wheel, not a line.

What I wound up not having time to include in this post was a little more about exactly what I've ritualized about domestic work as a result of this mindset, and I think while we're still in the week of the First Quarter I'd like to write a followup. Particularly because I think my attitude about sacred domesticity has already evolved beyond what I wrote in May.

So: onward.

The domestic rites I perform

As I mentioned in my original post, I don't do all the domestic work in our house, and this is important for several reasons. First of all, it helps reassure me that my owner and I aren't simply reproducing patriarchal paradigms; in theory I'd be happy to clean up after the cats and feed them, but my owner does it, just because. Secondly, there are domestic tasks I simply find unpleasant or outside my capacity, so I really appreciate when I don't have to do them; this includes preparing lots of meals, doing really deep surface cleanings, many types of furniture/house repairs, and some (though definitely not all) types of yard work. And lastly, my owner is what we refer to as a service-oriented dominant; in BDSM it's common to assume that the submissive partners are the ones who enjoy and ought to take care of domestic tasks for their dominants, but this is quite incorrect as plenty of dominants enjoy manifesting their power through taking care of their submissives. So that's another reason why most cooking is my owner's purview — after all, I'm his pet, and you're supposed to feed your pet, not the other way around.

However, I'm home most of the day, partly by choice and partly because the pandemic made my day job all remote, so at this point it only makes sense that I do most of the routine domestic work, and this is likely to continue as I stay in a professional field that operates online. The domestic work I perform can be broken down into a few categories:

- Tasks which have long been ritualized: Baking, whether from scratch or from a mix. Also cooking certain things my mother taught me to make. I may not be adventurous on my own in the kitchen, but following a precise recipe is a ritual to me and I find great rewards from executing it perfectly — likewise from sharing the result with somebody else. Outside the kitchen, I've also spent many years timing twice-seasonal whole-house cleaning-and-tidying days in relation to upcoming holidays; the implicit ritual is to sweep out the aftermath of the last holiday and make room for the next one. I meanwhile have a 3-week laundry cycle for spacing out what needs to be cleaned without sending a bunch of water to our septic field in one weekend; here is a ritual for keeping an organic system healthy. I also have created a 2-week cycle, with parts of the house mapped to days of the week, for staying on top of smaller cleaning or tidying activities; here is a series of tiny rituals for pacing my energy, creating less to do when the holiday cleaning times arrive.

- Tasks in which I'm actively developing ritual ideas: Fiber arts, mostly. So far I've written about my exploration of fiber arts as a matter of performing handcrafts for their own sake, but the making and mending of garments, as well as the creation of yarn and fabric, all falls into the realm of domestic work as well, insofar as it's work to do indoors and it's work performed to support other members of the household.

- Tasks where ritual still feels elusive: Doing dishes, oh lord. I manage to get most or all of them clean a several times a week, and I'm the one who's responsible for it because I have a preferred system for loading the dishwasher, but at age 35 (almost 36) I still struggle with making it a consistent practice. It doesn't help that when things need to be handwashed, I have sensory issues and one oddly specific trauma trigger around that activity. I would love to create an effective ritual to make this finally work out.

As might be apparent in my listing all of these tasks, I've mentioned ritual but I haven't said anything about going through a lot of magically- or religiously-infused ceremony. In some respects it's enough that I've created an elaborate system and protocol for how I handle certain domestic tasks. I don't think ritual living is necessarily about throwing on a lot of symbolic trappings to do ordinary things; to me it matters most that things take place in a planned sequence, on an intentional schedule, and it's through this very ordering of time that you can develop a special relation with the act you're performing. Making special time-space for the thing sacralizes the thing.

Nevertheless, as more and more domestic work in my life is sacralized through ritual, I do find myself looking for a way to tease out and heighten my actual sense of that sacredness — and that's where a symbolic language would come into play, along with cultivating a stronger sense of connection to the land on which this domestic work takes place.

Dreams of richer rhythms

The symbolic language I have in my mind for sacred domestic tasks is a musical language. In earlier times my ancestors had songs to accompany them during various sorts of work. I think everyone's ancestors have had such songs at some point or another. Depending on the culture, those songs persist into the present day. The songs would help measure a pace for what you were doing, remind you of the steps to perform, stop you from growing bored by repetition, and/or even help you enter a flow state.

Usually you would sing these songs with other people, as so much work was undertaken in groups — whether within a small household of several generations, a larger household of multiple families, or an entire community.[1] Teaching these songs would become an act of cultural transmission. Learning these songs would impart the fact that this work was valuable, and that you were supported in your work, not just left to fumble on your own through the world of what my generation tends to call "adulting."

So I think I would like to have more songs to sing when I perform domestic work. It would be better if I could sing them alongside other people — given where and how I live, unfortunately I don't have the gift of doing laundry with a group of friends, for example. But it would still mean something for me to learn songs from the past and keep them alive, and likewise to create new songs to eventually transmit to a child (along with the old songs).

Special songs have also long applied outside of "work of the home," to work beyond the home. Songs for many crafts, and songs for farming, songs for hunting, songs to sing to plants as you forage. I always love thinking about what I've learned of collecting elderberries or elder wood: in folk traditions across Europe you must ask the elder in a song or poem before you actually take something from her, otherwise it's bad luck. The practice of singing for domestic work is linked with singing as a general practice in land-connected societies.

Thus, in turn, I would like to be doing my domestic rituals in close rhythm with the land around me. Cooking things harvested or slaughtered by my own hands or the hands of neighbors and community members. Cleaning with materials that don't harm the local ecosystem. Making the act of tidying extend to disposing of or ending a dependency on items that derive from industrial, wasteful consumption. Creating clothes that are meant to endure for decades, using locally or personally grown fibers, and repairing my and others' apparel rather than just throwing it away. And so on, and so forth.

As I've written about before when discussing homestead dreams, this is very much more easily said than done. There are the challenges of living on occupied land, struggling to afford any land at all, and lacking the finances and training to just switch over to living off the land immediately; likewise there are the concerns of how "going it alone" off-grid is usually a recipe for disaster and conversely just starting a commune for everyone you know (instead of the right combination of people) also tends to turn bad. Therefore, while I could better realize an ethos of sacred domesticity within a homestead-commune type context, ideally a decolonized one, I also accept that it's going to take a lot of time and work to ever get that far; I even have to accept that although it's good to try in principle, my owner and I may simply not succeed.

So in the short term, I want to at least start singing. And there is something else I'd like to work on that's both approachable and very necessary: the problem of how to respond when the domestic environment is thrown out of rhythm.

Addressing rhythmic disruption

This is a very big psychological struggle for me. As alluded to in a footnote, carefully scheduled rituals arise often from instincts that represent my personal manifestation of autism. Routines, calendars, and other kinds of timekeeping — not capitalist linear timekeeping but still fixed, predictable arrangements — help me stay emotionally regulated and know that everything in life is going as it ought. So when a system for doing things becomes broken, or when there is no system, I don't cope well. I'm not just frustrated that my daily life has been inconvenienced; I feel almost physically thrown out of sync with the world, desperately searching for how to find the old rhythm again, or how to invent a new rhythm instead. If my arrangement of domestic tasks has to get adjusted, I really need a lot of warning. If a tool I need for a task is broken, I grow absurdly stressed until it's fixed.

Some things run even deeper, though. When the home itself feels "not as it should," this takes an exceptionally swift and strong toll.

Much of what I face in terms of anxiety is essentially the fear that I am going to lose my home or that my home is unsafe. Back when we were renting, this extended to terror about eviction — a lesser concern now, but it's been offset by regular flareups of fear about all the serious house problems that we, personally, are responsible for addressing if they arise. Fire hazards. Water intrusion hazards. Pests. Fire hazards. Structural stability. Bad air, if it's not just coming from outside. Bad water, if it can't be traced back to the town wells. Fire hazards. And if I haven't mentioned it enough, fire hazards. Of course we have insurance, but that never means much in my head; insurance money helps to replace what was lost, yet some unique things can never be replaced, and I fear specifically the chaos of being temporarily displaced by having an uninhabitable dwelling.[2]

Thus I fret endlessly and no doubt excessively about the slightest small disruption in the home that could ever be a sign of a bigger disruption looming. Unfamiliar smells, especially bad ones, mean fire risk or toxicity. Odd sounds mean a veritable roulette wheel of bad possibilities. One ant means the walls are crawling with them. We have a few maintenance projects that we haven't had the money or time to do yet, like repair and/or replace the house's siding and window frames, and it makes me feel like I'm inside a cabin made of popsicle sticks. I've grown self-aware enough about how the intensity of my reaction to these situations is the real problem, not the reaction itself — obviously, odd smells and sounds should be investigated, pests should be handled rapidly, and repairs shouldn't be delayed if we can help it — but therapeutically it's still a work in progress for me to train that reaction to dial down or never intensify in the first place.

In other words, for being someone who cares so much about keeping home a sacred place, I have a lot of trouble simply experiencing that sacredness and not thinking it's about to be desecrated at any moment.

Some of that would be addressed in an instant if we just had more income. We could proactively get ahead of certain things I'm afraid of before they'd ever become a problem, and if some disruptions arose I would at least have the assurance that they wouldn't last as long as they would when we were perpetually broke. However, I know my psychology well enough to suspect that I would still fight anxiety over domestic disruptions because of having those disruptions at all.

On that front, I'm starting to wonder about two simultaneous strategies. One is to continue doing what I've already been trying to do for a while: accept the impermanence of things. Yes, in recovering animism and harmony with the natural world, there is the need for ritual, ritual, ritual, and thus rhythm, rhythm, rhythm, order, order, order. But the grandest rhythm of all is chaos. Things come together, then they break apart. Nothing is really constant, it's always changing. I need to accept that I will never have one absolute, fixed, eternally consistent home life. Similarly, I need to accept that when disruption does occur, this too shall pass, and some new rhythm will eventually be discovered if I can only be patient.

The other strategy is something that's come to me in reading Mhara Starling's Welsh Witchcraft, referenced last week as well. Despite my very strongly Cymric upbringing, many aspects of Cymric folklore are still outside my immediate knowledge base, especially when it comes to traditions that are preserved most in actual Cymric-speaking communities instead of anglophone families like mine. So in reading this book, I've learned for the first time about the Cymric concept of the bwbach.[3]

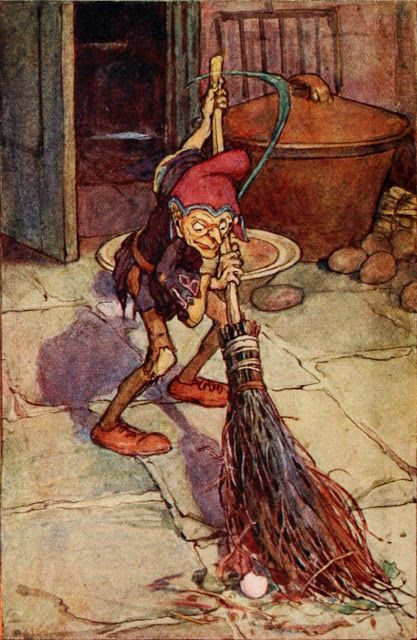

This a household spirit, in the loosest terms. Apparently it more precisely fits into fairy lore; analogues elsewhere in Britain include the Scottish brownie (brùnaidh) or Anglo-Scottish hob. For a non-fairy but familiar example to some contemporary pagans/animists, think of the Roman Lares. With the bwbach and probably some related things, there isn't necessarily a uniform belief about whether a bwbach is tied to one home and stays there from owner to owner, or whether it follows an owner around. But the bwbach is certainly an entity with which it pays to cultivate a good relationship; if you have a friendly, helpful bwbach then it will make sure things around your home go well, whereas if the bwbach becomes unhappy about something your home will start to have problems, like faster food spoilage or things breaking or, well, any of the other household things I'm always afraid of going wrong.

Now, when I wrote my first post about sacred domesticity I said I don't really believe in — that is to say, I don't really make use of the idea — of household spirits. But ever since reading about bwbachod, I've been wondering if I would benefit from thinking in terms of their existence. Back when my owner and I lived in the rental unit that I nickname the Mold Palace and have probably discussed here before, I finally came to understand what hauntings really feel like; a haunting is an animist way of processing something being very aggressively dangerous or unsettling in your living space. On an empirical level I believe the townhouse "just" had mold, but from an animist perspective that place was haunted. I've never seen a ghost, I don't know if I'm capable, but sometimes it just makes sense to use the language of haunting to describe a bad experience.

Why shouldn't I consider adopting the bwbach for similar purposes? I think the mold problem was too severe to just relate to it in terms of an unhappy bwbach — haunting is the more potent, inherently negative term, the spirit of that dwelling was simply not a thing you could feel good about — but maybe in the place I live these days, I can try to reach out ritually to the concept of a bwbach and see where that takes me. I'm not looking for control, for I know that appeasing it wouldn't stop it from doing what it liked; this is a psychological working, not a physical one. But in the psyche, consensus reality is not always what's important. If I fear the house falling apart around me, then let me personify it so that it feels easier to relate to events happening that would otherwise be random and meaningless. A bwbach could help create meaning, the most powerful coping mechanism of all.

Compensation & reward, revisited

That's enough for now about what I have to struggle with in creating sacred domesticity within my life. To close my thoughts for the week, I want to come back to the ways that sacred domesticity is good for me — the true rewards that go beyond my material wish for our household to have an income where spending time on chores felt fairly offset.

When homemaking is going well, I know it because life in the home and sometimes outside the home simply flows better. It's easier to think, move, and do when there's no clutter; I don't mean having an absolutely spartan amount of possessions, but I mean that everything is placed where you can find it easily later and arranged in an intuitive pattern. Likewise, our bodies are more grounded when there's good, fresh-made food inside them. We feel safer and calmer when we can wear clean things and we're not surrounded by grime, dust, or stinking drains and bins. This applies even if you don't have anxiety and sensory issues like my own. Even in a good home, with a good bwbach if you will, entropy will eventually its way and so it's our place to steward that environment just as it's our place to steward the land we live on. In the moments when I have really made the home, I feel a quiet but distinct euphoria.

I suppose this is what reactionaries, especially within the tradwife movement, try to point to for a woman's place being in the home. I hate this not just because I hate lifestyle fascism but also because the homemaking euphoria I get really doesn't feel too strongly correlated with what my gender is doing. I was still a young man when I realized I would be most comfortable as a homemaker (or, more precisely, spending about half my daily work hours on writing/other art and the other half on domestic tasks and garden tasks). I had this realization several years before I determined I wasn't a man anymore. I gleefully savored the idea of becoming a "househusband." If I ever become a man again then that idea might well resurge. The reactionary counterargument would probably be that whatever gender I claim to be at the time, the existence of my ovaries somehow predisposes me to seek domestic work anyway; at that I would observe how I had cismasculine levels of testosterone for three and a half years, overriding the amount of estrogen or other "female hormones" that my ovaries put out.

Well, that probably still wouldn't convince some particularly diehard gender essentialists, but fuck them, etc. In any case, though, I will admit that no matter how thoroughly my owner and I defy patriarchal stereotypes together, the very association of domestic work with femininity does give me pause, sometimes in paralyzing moments of self-scrutiny. I ask myself things like:

As much as I enjoy domestic work, should I be careful not to let it consume my personality?

What does it imply for me, gender-wise, if I'm not only responsible for most day-to-day homemaking but also eventually for taking care of a child at home for more than half the day?

As a kinkster, I claim not to get much out of "service-oriented submission," but if I non-sexually enjoy performing domestic work that my owner isn't doing himself, to a casual observer isn't this indistinguishable from offering my owner "service"?

These are neuroticisms; the answers to each are very simple if I want them to be. If I don't want to grow so attached to domestic work that it consumes me, then I just won't. If I'm self-aware about the areas in which my domestic work and so-called emotional labor can be conflated with feminine stereotypes, then by definition I'm not just a stereotype. And if the domestic work I perform isn't a kink thing, then it isn't a kink thing.

But it's telling that my mind still feels obliged to repeatedly ask itself such questions and repeatedly supply those basic answers. For one thing, the neuroticism is demanded by the age in which I live. Simultaneously, though, the assumption that domestic work is women's work goes back far beyond the birth of capitalism; if it's not a universal trait of human cultures, it's at least ragingly common and it informs all that's known of the cultures through which my own ancestors have passed. In embracing domestic work, I run up against other questions I've repeatedly asked myself about why (or why not) my gender could be considered "woman" today.

As I said at the conclusion of that linked post, though, the fact of the matter is I'm not a woman. I'm a witch. Easily mistaken for that one broad gender category, but much more precise. And as I seek to sacralize domestic work, perhaps this does after all align such work with my gender, but only along the vector of magic. Witches of all anatomies, presentations, identifications, and kinks are welcome together in exploring sacred domesticity. Even having written this, I'm already more curious about how much further I can go.

[1] Rises in air pollution correlating with rises in autism diagnoses have, among other factors like the rigid thinking conducive to digital programming, caused some people to speculate that autism is a modern condition. I don't think so at all. Leaving aside changeling legends, I often feel as if my own autism is what drives me toward pre-industrial, animist living schemes (even though I hardly reject all modern technology). The autistic penchant for schedules and traditions feels like ritualism erupting into the modern world; and the common neurodivergent need for mirroring others' activities in order to get things done speaks to a time when humans did a lot more things side by side instead of being sequestered into nuclear units for everything.

[2] In addition to the even more primordial fear that something in my home could simply kill me.

[3] Pronounced "BOO-bakh."

Another week, another newsletter. Thank you for reading, of course. It's been a little while since I asked for some financial help with making Salt for the Eclipse keep happening: if even just half the people reading this were willing to do a paid subscription at $1/month, I would break even on the cost of putting this out. There are higher subscription tiers you can consider if you'd like to make that even easier and maybe help me make a slightly better living from writing; but even $1/month from enough people would make a huge difference. Thank you again.

In any case, next week it's time for another holiday post, as we'll have just passed Calan Awst (Lughnasadh or Lammas to many of you) and I'd like to devote some attention to what people understand of "the Celtic calendar," especially as it informs the Wheel of the Year. After that, there will be a fresh post about death work, for paid subscribers only.

Member discussion